The JOBS Act and Crowdfunding

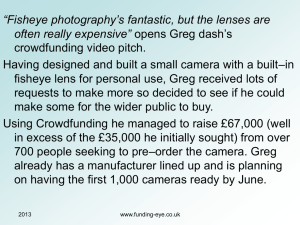

advertisement