The Crowdfund Act's Strange Bedfellows

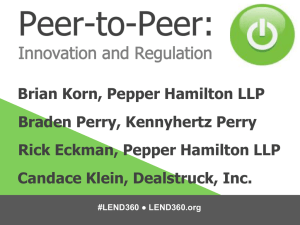

advertisement