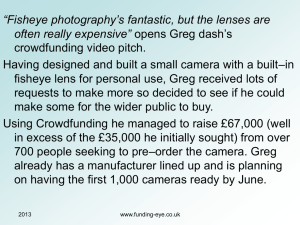

crowdfunding: the real and the illusory exemption

advertisement