Timeline of Western Philosophy

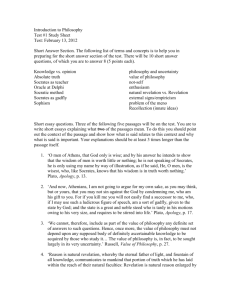

Introduction to Philosophy Study Sheet #4

Timeline of Western Philosophy

Ancient Philosophy (600 BCE – 500 CE)

1000 BCE

Thales (624-545)

Pre-Socratic Philosophers (600-470)

500 BCE

Socrates (470-399)

Plato (427-347)

Trail and execution of Socrates (399)

Plato establishes the Academy in Athens (387)

Aristotle (384-322)

Terminology

Law of Athens (Crito): Socrates personifies the Laws of Athens to substantiate his argument that it would be wrong to flee Athens.

Social Contract: Social contract arguments typically posit that individuals have consented, either explicitly or tacitly, to surrender some of their freedoms and submit to the authority of the ruler or magistrate (or to the decision of a majority), in exchange for protection of their remaining rights.

Justice (Platonic): Excellence in function for the whole; in a just society each individual performs his or her natural function according to class; in a just individual, reason rules the spirit and the appetites.

Platonic Forms : In Plato’s metaphysics, the highest level of reality consist of timeless essences called ideas, archetypes, or Forms. Forms are independently existing entities in the world of Being, which determines the nature of the particular things of this world of becoming. Non-spatial, non-temporal objective ‘somethings’ (ideas, archetypes) known only through thought and that cannot be known through the senses.

Knowledge (Plato): Knowledge is unchanging and always of essences (i.e. Forms). Disagreement is only possible on the level of becoming.

Becoming (in Plato): The ‘world of becoming’ is the changing world of our daily experience, in which things and people come into being and pass away.

Being (in Plato): The ‘world of Being’ is the realm of eternal Forms, in which nothing ever changes. It is, for Plato, reality, and in general being is used by philosophers to refer to whatever they consider ultimately real (substance, God).

1

Definitions are from a variety of sources and have been abbreviated. Primary sources include: The Great

Conversation: A Historical Introduction to Philosophy, Norman Merchert; The Big Questions: A Short Introduction to Philosophy, Robert C. Solomon and Kathleen M. Higgins; Introduction to Philosophy: Classical and

Contemporary Readings, Louis P. Pojman and James Fieser; Archetypes of Wisdom: An Introduction to Philosophy,

Douglas J. Soccio; Philosophy: The Power Of Ideas, Brooke Noel Moore and Kenneth Bruder For more extensive definitions, a good source can be found online: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Glossary_of_philosophy

1

Introduction to Philosophy Study Sheet #4

Essence (or an essential property): The necessary or defining characteristics or properties of a thing.

The essence of a person is that without which we would not say one is that particular person.

Transcendental (Plato): Assertion there is a plane of existence that transcends, or goes beyond, our ordinary perception of things.

Readings (key passages)

Crito, Plato

SOCRATES: We should not then think so much of what the majority will say about us, but what he will say who understand justice and injustice, the one, that is, and the truth itself. So that, in the first place you were wrong to believe that we care for the opinion of the many about what is just, beautiful, good and their opposites.

(48a)

----------------

SOCRATES: Above all, is the truth such as we used to say it was, whether the majority agree or not, and whether we must still suffer worse things than we do now, or will be treated more gently, that, nonetheless, wrongdoing or injustice is in every way harmful and shameful to the wrongdoer? Do we say so or not?

CRITO: We do.

SOCRATES: So one must never do wrong.

CRITO: Certainly not.

SOCRATES: Nor must one, when wronged, inflict wrong in return, as the majority believe, since one must never do wrong.

CRITO: That seems to be the case.

(49b-c)

-----------------

SOCRATES: Look at it this way. If, as we were planning to run away from here, or whatever one should call it, the laws and state came and confronted us and asked: ‘Tell me, Socrates, what are you intending to do? Do you not by this action you are attempting intend to destroy us, the laws, and indeed the whole city, as far as you are concerned? Or do you think it possible for a city not to be destroyed if the verdicts of tis courts have not force but are nullified and and set at naught by private individuals?’ What shall we answer to this and other such arguments? For many things could be said, especially by an orator on behalf of this law we are destroying, which orders that the judgments of the courts shall be carried out.

Shall we say in answer, ‘The city wronged me, and its decision was not right.’ Shaw we say that, or what?

CRITO: Yes, by Zeus, Socrates, that is our answer.

SOCRATES: Then what if the laws said: ‘Was that the agreement between us, Socrates, or was it to respect the judgments that the city came to?’ And if we wondered at their words, they would perhaps add: ‘Socrates, do not wonder at what we say but answer, since you are accustomed to proceed by question and answer: Come now, what accusation do you bring against us and the city, that you should try to destroy us…..Do you think you have this right to retaliation against your country and its laws. That if we undertake to destroy you and think it right to d so, you can under taken to destroy us, so are as you can, in return? And will you say that you are right to do so, you who truly care for virtue? Is your

2

Introduction to Philosophy Study Sheet #4 wisdom such as not to realize that your country is to be honored more than your mother, our father, and all your ancestors, that it is more to be revered and more sacred, and that counts for more among the geos and sensible men, that you worship it, yield to it, and placate its anger more than your father’s? You must either persuade it or obey its orders, and endure in silence whatever it instructs you to endure, whether blows or bonds, and if it lead you into war to be wounded or killed, you must obey. To do so is right, and one must not give way or retreat or leave one’s post, but both in war and in courts and everywhere else, one must obey the commands of one’s city and country, or persuade it as to the nature of justice. It is impious to bring violence to bear against your mother or father; it is much more so to use it against your country.” What shall we say in reply, Crito, that he laws speak the truth, or not?

CRITO: I think they do.

(50a-51c)

Republic, Plato

SOCRATES: Why, have you never noticed that opinion without knowledge is always a shabby sort of thing? At the best it is blind. One who holds a true belief without intelligence is just like a blind man who happens to take the right road, isn’t he?

----------------------

SOCRATES: First, we must come to an understanding. Let me remind you of the distinction we drew earlier and have often drawn on other occasions, between the multiplicity of things that we call good or beautiful or whatever it may be and, on the other hand, Goodness itself or Beauty itself and so on.

Corresponding to each of these sets of many things, we postulate a single form or real essence, as we call it.

GLAUCON: Yes, that is so.

SOCRATES: Further, the many things, we say, can be seen, but are not objects of rational thought; whereas the Forms are objects of thought, but invisible.

----------------------

SOCRATES: Conceive, then, that there are these two powers I speak of, the good reigning over the domain of all that is intelligible [and] the Sun over the visible world…at any rate you have these two orders of things clearly before your mind: the visible and the intelligible?

GLAUCON: I have.

SOCRATES: Now take a line divided into two unequal parts, one to represent the visible order, the other the intelligible; and divide each part again in the same proportion, symbolizing degrees of comparative clearness or obscurity.

------------------------

SOCRATES: You have understood me quite well enough. And now you may take, as corresponding to the four sections, these four states of mind: intelligence for the highest, thinking for the second, belief for the third, and for the last imagining. These you may arrange as the terms in a proportion, assigning to each a degree of clearness and certainty corresponding to the measure in which their objects possess truth and reality.

------------------------

3