MEASuRING HORMONES - Society for Endocrinology

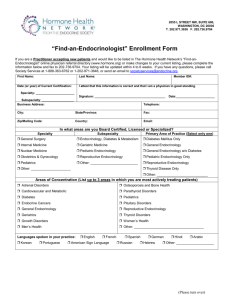

advertisement