1 CLE Presentation Understanding a Company's General Ledger for

advertisement

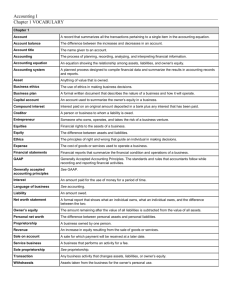

CLE Presentation Understanding a Company’s General Ledger for the Business Litigator William C. Cleveland Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice, LLP 5 Exchange Street Charleston, SC 29401 ______________________ Several years ago I was in a lawsuit involving an automobile broker whose job it was to buy used cars at the Florida auto auction and deliver them to local dealerships in Charleston. He came up with a clever plan to improve his cash flow. Rather than buy six cars for the six separate local dealerships, he decided it made more sense to buy one car and make five copies of the paperwork relevant to the purchase. He delivered the paperwork to his confederates within the dealerships. They in turn issued checks to the broker, purported to enter the car into inventory, waited for the requisite time under the dealership’s policy for unloading used cars that wouldn’t sell, entered the car as having been sold for the distress price and split the difference between the purchase price and the sales price. While reviewing the dealerships’ general ledger in an attempt to determine the scope of the fraud within the dealerships, I found myself totally frustrated by my inability to understand how credits and debits work within the general ledger. As an example, sales revenue was entered as a credit and recorded as a negative number whereas cash was entered as a debit and recorded as a positive number. The forensic accountant we hired could not explain it to me in a way that I could understand. The purpose of this presentation is to explain the fundamentals of double entry bookkeeping and how to find your way around a company’s general ledger. Knowing the basics of what a general ledger is, how the entries are made to it and how to find accounts within the general ledger that may be relevant to your lawsuit may give you an edge that you otherwise wouldn’t have. Let’s look at two examples of double entry bookkeeping in action. In the first, a company borrows $100,000 to buy equipment for its operations. The bookkeeper first debits the equipment account in the amount of $100,000 and then credits the accounts payable account $100,000. 1 In the second, the company pays $1000 for supplies, The bookkeeper debits the supplies account in the amount of $1000 and credits the cash account negative $1000. This article attempts to explain what those terms mean and why it is done that way. Let’s begin with a short overview of accounting basics and then move into an explanation of what double entry accounting is and how it works. There are four main types of financial statements, the balance sheet, the income statement, the statement of changes in owner equity and the statement of cash flows. The balance sheet is a snapshot of a company’s financial information at a given point in time. It shows the company’s assets, liabilities and net worth or equity. The fundamental accounting equation is assets minus liabilities equals equity or net worth. ASSETS – LIABILITIES = EQUITY The things that a company owns, its buildings, its equipment and its cash are its assets. The things that a company owes such as the money it borrowed from its bank, amounts owed the suppliers or wages owed to employees are liabilities. Let’s see how the fundamental accounting equation works with the operations of a thriving down town business. 2 WALKER’S LEMONADE STAND Walker operates his lemonade stand in front of the Charleston Library Society where his grandmother works. Walker has saved $2 from his allowance which he contributes to the lemonade stand business in order to make change for his customers. Walker’s mother, Meg, makes up a batch of lemonade which she gives Walker in exchange for his promise to pay her $2 once he sells all 30 cups of lemonade at 10¢ a piece. Looking at the fundamental accounting equation, Walker’s assets are the sum of the $2 he contributed to the enterprise, plus the $2 of inventory that is recorded at the cost, not the value, of the batch of lemonade. His liabilities consist of the $2 he owes Meg. Therefore, his equity or net worth is $2. ASSETS – LIABILITIES = EQUITY $4 $2 $2 Sometime in the middle ages, bookkeepers in Venice decided that the presentation of a company’s financial condition would be clearer if liabilities moved to the right side of the equation so that assets equal liabilities plus equity. ASSETS = LIABILITIES + EQUITY They further determined that the presentation could be improved if the equity portion of the equation were moved below the liabilities. ASSETS = LIABILITIES + EQUITY Looking at Walker’s balance sheet after Meg has provided him with his first batch of lemonade but before he conducts his sales, his cash on hand is the $2 he brought to the enterprise plus the cost, not the value, of his inventory which is $2, resulting in his total assets equaling $4. 3 His accounts payable, the $2 he owes Meg, is his only liability and his equity is the difference between the assets and the liabilities, which at that point in time is also $2. His total assets on the one hand equal the total liabilities and net worth on the other. They are balanced. The reason we call this particular financial statement a balance sheet is because the assets on the one side are always, always, in balance with the liabilities and equity on the other side of the balance sheet. Let’s see what happens to Walker’s balance sheet after his first day of sales. His cash on hand is now $5, the sum of the $2 he brought to the enterprise and his $3 of revenues. The accounts payable remain the $2 that he owes Meg and his net worth is now increased to $3. Therefore, if we take a snapshot of Walker’s assets, liabilities and equity after his first day of sales, the assets on the one side total $5 and the liabilities and equity on the other side total $5. Double entry bookkeeping gets its name “double entry” from the fact that in every transaction the bookkeeper will enter both the source of the money for the transaction and what the money is used to acquire or pay for. Let’s look at the sources of Walker’s financial transactions 4 that occur on that first Saturday. The first asset is the $2 of cash. The source of that cash is the $2 invested by Walker when he started the business. The second asset that Walker has is his inventory. The source of the money used to acquire that inventory is the $2 that Walker promised to pay Meg. After Walker’s first day of sales his assets are $5. $2 of those $5 were invested by Walker. The source of the remaining $3 are the revenues that Walker generated from the sale of his lemonade. Generally speaking, the source of the money to buy the assets that a company owns comes from one of three places. First, the liabilities are the money that the company borrows from banks or others or the obligation it undertakes when it buys assets on credit. Second are the invested funds and third are the revenues from the operation of the business. Money is used to do one of three things: to acquire assets, pay expenses or make distributions. This illustration, as simple as it is, is the fundamental basis of double entry bookkeeping, which is that in every transaction you ask the question first, what does the money acquire or what is it used to pay for and second what is the source of the money for that transaction. As will be explained in more detail below, the bookkeeper records in the appropriate accounts both the source of money and the use of the money for every transaction. Let’s see how this relates to the dollars that Walker’s business generates. ASSETS = LIABILITIES + EQUITY The fundamental accounting equation is that assets equal liabilities plus equity. The expanded fundamental accounting equation introduces the components of equity. Equity is made up of either contributed capital or revenues from the operation less the expenses and less any distributions paid back to stockholders. 5 EQUITY = CONTRIBUTED CAPITAL + REVENUES – EXPENSES – DISTRIBUTIONS1 Therefore, the expanded equation using the components of Equity is ASSETS = LIABILITIES + CONTRIBUTED CAPITAL + REVENUES – EXPENSES – DISTRIBUTIONS After his first day of sales, Walker’s assets are $5. This is equal to his liabilities of $2 plus his contributed capital of $2, his revenues of $3 less his expenses of $2, less the distributions, which in this case are zero. ASSETS = LIABILITIES + CONTRIBUTED CAPITAL + REVENUES – EXPENSES – DISTRIBUTIONS $5 $2 $2 $3 $2 $0 Restating this equation so that we have no negative numbers requires moving the expenses and the distributions over to the left side of the equation such that assets plus expenses plus distributions on the one hand equal the liabilities plus contributed capital plus revenues on the other. ASSETS + EXPENSES + DISTRIBUTIONS = LIABILITIES + CONTRIBUTED CAPITAL + REVENUES This should look familiar because the equation is the same as the source/use illustration above. The accounts on the right hand side of the equation are primarily the source of the money 1 Revenues and expenses, which are components of equity, are not shown on the balance sheet. But, they are shown on the income statement. And, all of these accounts are part of the general ledger. 6 for all transactions and the accounts on the left side of the equation are the accounts in which the money is used to acquire something or pay for something. The accounts on the right hand side are called the credit accounts. They are generally the source of the money for every transaction. The accounts on the left hand side are called the debit accounts. The debit accounts are generally how the money is used in every transaction. Double entry bookkeeping is simple if you recall that every financial transaction requires the bookkeeper to account for, and record, both the source of the money and how the money is used. Double entry bookkeeping incorporates the truism that if the transaction leaves the balance sheet in balance, then the transaction itself must be balanced. This is done by recognizing that in every transaction there is a source of the money that is used and there is a purpose for which the money is used and the two are equal. The way that is done is through the establishment of accounts for all aspects of a company’s business. An account is simply a record of money paid in and taken out for various purposes. Walker’s accounts include his cash, his inventory, his expenses, his accounts payable and his contributed capital. The Venetian businessmen that we talked about earlier decided that it would be helpful to put a line down the middle of the account so that money paid into the account could be put on one side of the line and the money taken out of the account would be put on the other side. Because they look like the letter T, these are called T accounts. Notice that the plus (+) sign on the assets accounts is on the left side of the ledger whereas the plus (+) sign on the liability accounts is on the right side. One of the brilliant insights of double 7 entry bookkeeping is recording increases to the assets accounts on the left side of the account ledger and increases to the liability and equity accounts on the right side of the account ledger. Doing it this way results in all right hand ledger entries always equaling the total of all left hand ledger entries for every transaction. This enables the bookkeeper to quickly see whether entries are being recorded accurately. Let’s see what that means and why it works. At any point in time a company’s balance sheet will present the assets on one side and the liabilities and equity on the other. And, they will always balance. For that to be true, it means that every transaction must leave the assets on the one side in balance with the liabilities and equity on the other side of the balance sheet. In order for that to happen, each transaction must either affect both sides of the balance sheet in an equal amount or it must affect only one side and operate so as to have no effect on that side’s total. As stated above, since each transaction must leave the assets, liabilities and equity of a business balanced, double entry bookkeeping is based on the premise that at the end of each transaction, the balance sheet will remain balanced. ASSETS = LIABILITIES + EQUITY Let’s simplify the analysis and assume Walker’s Lemonade Company has no equity. This results in it having only two types of accounts on its balance sheet, assets and liabilities. In this situation, a transaction can affect either both sides of the balance sheet or only one side. Assume that Walker’s Lemonade Stand has only three accounts: Cash, Inventory, and Accounts Payable to Meg. The first two are asset accounts and the third is a liability account. WALKER’S LEMONADE STAND ACCOUNTS Asset Accounts (+) Cash on Hand (-) Liability Accounts (+) Accounts Payable to Meg (-) (+) Inventory (-) Let’s see how recording a transaction would look if the plus (+) sign were on the left side of all accounts. In our first transaction Walker promises to pay Meg $2.00 in exchange for a $2.00 batch of Lemonade. To record that transaction, we increase the amount of inventory by $2.00 and we increase the amount of accounts payable to Meg by $2.00. 8 Example One Asset Accounts (+) Cash on Hand (-) Liability Accounts (+) Accounts Payable to Meg (-) $2.00 (+) Inventory (-) $2.00 We can easily see that this transaction increases both the assets and the liabilities by the same $2.00 and therefore would leave the balance sheet balanced. This is a transaction that affects both sides of the balance sheet. The important point is that, because the plus (+) sign is on the left side of the accounts payable account, both of the entries are on the left side of the ledger accounts. In our second example Walker takes $2.00 of his cash and buys a batch of lemonade from Meg. To record this transaction we enter an increase in inventory of $2.00 and a decrease in cash by $2.00. Example Two Asset Accounts (+) Cash on Hand (-) Liability Accounts (+) Accounts Payable to Meg (-) $2.00 (+) Inventory (-) $2.00 9 In this example the transaction affects only one side of the balance sheet, the asset side. The transaction would not change the total of assets and therefore would leave the balance sheet balanced. All of that is fine, except we now have one entry on the right side of a ledger and one on the left side of a ledger. Double entry bookkeeping figured out that if the increases to the liability accounts were entered on the right side, rather than the left side, of the ledger (that is to say that the plus (+) sign is on the right side) then good things would happen. Let’s see what that is. In the illustration below, the plus and minus signs are switched on the Accounts Payable to Meg account. When we enter the first example with the ledgers set up this way, the amount of the increases and decreases stay the same as before. But, now the entries on the right side of a ledger account equal the entries on the left side of a ledger account. Example One Asset Accounts (+) Cash on Hand (-) Liability Accounts (-) Accounts Payable to Meg (+) $2.00 (+) Inventory (-) $2.00 In double entry bookkeeping, entries to the left side of any ledger account are called debits. Entries to the right side of any ledger account are called credits. Depending on whether the account is an asset account or a liability account, some debits increase the amount of an account, such as when debits are made to the left side of the cash account. However, debits made to the left side of an accounts payable account reduces the amount in the account. Therefore, you should think of debits and credits as simply indicating on which side of an account an entry is made. The other way to think of debits and credits is that debits always are entered to show what the money in a transaction was used for and credits are entered to show the source of the money for the transaction. Double entry bookkeeping provides added degrees of reliability and accuracy in the bookkeeping process by incorporating the assumption that in every financial transaction there will be a source of money that will be used to either acquire assets, pay expenses or pay distributions 10 to shareholders. The source entries, the credits, will always equal the use entries, the debits, for each transaction. In a large company, the general ledger may contain hundreds if not thousands of separate accounts. The summary of all of the accounts is contained in the Chart ofAaccounts. It will contain the number assigned to each account and a description of what that account is. Determining how many accounts a company needs is a matter of judgment. Too few accounts make it difficult to analyze what is really occurring in the business. Too many creates needless detail. For instance, a landscaping company may want to keep track of income from the sale of plants separately from that received from structural items such as rocks and wood. A retail jewelry store, on the other hand, may want to track income from sales of jewelry separately from income from sales of services such as cleaning and polishing. Neither business would have use for the unique categories used by the other. Double entry bookkeeping normally entails a 3-step process. The first step is entering the transactions in the daily journal, the second is posting the journal entries to the general ledger and the third is preparation of the financial statements. When entering the transaction to the daily journal, the first step is to record the debits to each account for which the money in the transaction was used. The second step is to enter all of 11 the credits, describing all accounts which provide the source of the money for the transaction. As we saw above, the credits will equal the debits for every transaction. In posting the accounts from the Daily Journal to the General Ledger the bookkeeper will record the information for each transaction into the appropriate account. In the example above, the two relevant accounts are the inventory and accounts payable accounts. Notice that the debit to the inventory account is entered on the left hand side of the ledger (as is true whenever a debit is entered). Likewise the credit to the accounts payable account is entered on the right side of the ledger. Double entry bookkeeping provides an immediate test for the accuracy of the information being recorded because in every transaction the source of the money must equal the amount of money used. Another way of saying that is that the credits for the transactions must equal the debits. If they do not, then an error has been made in the bookkeeping process. Finally, at whatever time interval the company decides is appropriate, the bookkeeper will aggregate the information contained in the general ledger to prepare the financial statements for the company. The information contained in the 4 basic financial statements are interrelated. As the slide below shows, the net income from the Income Statement is a component of the Statement of Retained Earnings. The total of retained earnings is carried forward to the Balance Sheet and the cash from the Balance Sheet should equal the ending case in the Statement of Cash Flows. 12 Let’s look at examples that occur in Walker’s business and see how they should be recorded. Walker borrows $10.00 from his grandfather to buy a new lemonade stand. The $10 in this example is used to acquire equipment. Therefore, the bookkeeper should debit $10 to the equipment account. Because the source of the money is Walker’s $10 debt to his grandfather, the bookkeeper should credit $10 to the accounts payable account. 13 Walker pays Meg $2 that he owes her. In this example, the money is used to satisfy an obligation to Meg. Therefore, the bookkeeper should debit $2 to the accounts payable account. Since the source of the money is Walker’s cash, the bookkeeper should credit $2 to the cash account. Accountants often use the letters DR and CR to stand for debits and credits. You can remember that the credits are always on the right side of an account because the letters CR can be remembered to stand for “column on the right.” 14 CONCLUSION The following bullet points summarize what we have covered. • IN EVERY TRANSACTION THE MONEY COMES FROM ONE OR MORE ACCOUNTS AND IS USED IN ONE OR MORE ACCOUNTS. • THE SOURCE IS ENTERED AS A CREDIT IN THE SOURCE ACOUNT. THE USE IS ENTERED AS A DEBIT IN THE USE ACCOUNT. • THE GENERAL LEDGER CONTAINS A RUNNING TOTAL OF ALL ENTRIES IN ALL ACCOUNTS • THE CHART OF ACCOUNTS LISTS ALL ACCOUNTS • TO DEBIT AN ACCOUNT IS TO MAKE AN ENTRY ON THE LEFT SIDE OF THE ACCOUNT • TO CREDIT IS TO ENTER IN THE COLUMN ON THE RIGHT The information contained in the general ledger accounts is a contemporaneous, chronological itemization of money paid in and paid out for all the things a company does. Often, it will be a more accurate description of things that occurred in the company than will be post-litigation reports generated in response to discovery. 15