College Credit for Heroes Report to the 83rd Legislature and

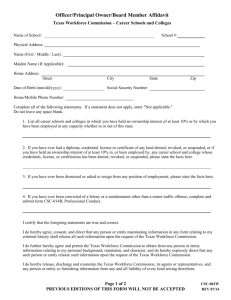

advertisement