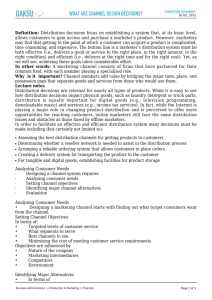

Design and selection of industrial marketing channels

advertisement