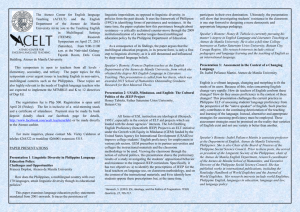

mAnILA by nIGhT - Kritika Kultura

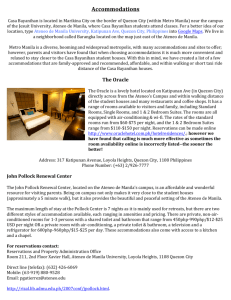

advertisement