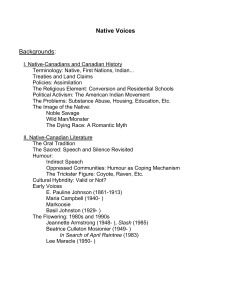

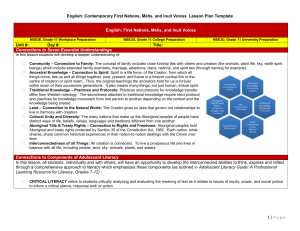

English 12 First Peoples Teachers Resource Guide

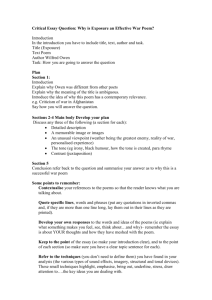

advertisement