Victor Chang School Project Material 2012

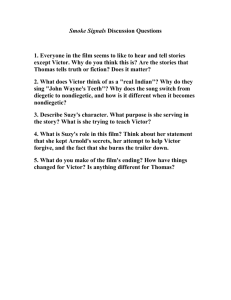

advertisement

Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 SECTION 1: CONTENTS About the heart ‘Heart’ poem Illustration of the heart Victor Chang’s Artificial Heart Heart Transplants Heart Facts Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 ABOUT THE HEART The heart is a vital organ. It’s the muscle that pumps blood to all parts of your body, providing every organ, muscle and tissue cell with oxygen and the nourishment you need to live. The heart is the first organ to start functioning in a developing embryo, and it has to function very efficiently if the baby is to grow and survive. The heart has a right and left side, separated by a wall of muscle. Each side has a small collecting chamber called an atrium, which leads into a large pumping chamber called a ventricle. So there are four chambers in all: the left atrium; left ventricle; right atrium and right ventricle. One-way valves at the entrance and exit of each ventricle chamber make sure the blood keeps moving in the right direction. Blood that has been through the body enters the heart through the right atrium. As this blood has had its oxygen and nutrients removed by the body’s cells, the right ventricle pumps it to the lungs to receive a fresh supply of oxygen. It then returns to the heart via the left atrium, and then the left ventricle pumps this oxygen-rich blood back out through the body. In order to produce the higher pressure needed to send blood right around your body, the muscles of the left ventricle are larger and thicker than the right ventricle (which only needs to pump blood through the lungs). Blood flows round your body through a network of blood vessels called arteries and veins. Arteries carry blood away from the heart, whereas veins bring blood back to the heart. Between them are capillaries, which are often microscopic in size, and distribute the blood through your body tissues. Together the heart and blood vessels make up the circulatory system. The largest artery, leading straight out of the heart, is the aorta. This branches out to carry blood to your heart muscle, brain, arm and legs and organs inside the chest and abdomen. Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 ‘HEART’ From "Corona radiata" by Alice Major. Used with permission of The St. Thomas Poetry Series. Mammal The heart makes a journey through time. Begins when the old amoebae drift of nutrients from cell to cell will suffice no longer. First a fish's heart - a tube of knuckled coral, ancient, Paleozoic invention. Bends into a horseshoe, becomes amphibian, Devonian, double-chambered like the frog's croak . Contorts, squeezes, divides again into a snake's heart. Three rooms - two atria to collect, one large cavity to force out. One last division - another phylum forms, four chambers now. Symmetric. A pump for warm blood. The little mammal curls in her nest, blind shrew with clever paws. She has travelled through five hundred million years. Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 ILLUSTRATION OF THE HEART Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 ARTIFICIAL HEARTS An artificial heart is a man‐made device that can replace one side of a person’s failing heart. It’s usually made of metal and plastic components and consists of a small pumping chamber lined with a special material to prevent blood clots. It can be implanted into the patient’s body or left outside, depending on the type and the circumstances. Depending on which side of the heart is being supported, blood will enter the artificial heart from the patient’s left or right atrium and be pumped into the aorta or pulmonary artery. The device is powered by either compressed air or electricity. The pumping function is regulated by a control console, which is connected to the artificial heart by a thin cable. The control console itself may be a large box on wheels that can be moved with the patient, or it can be a much smaller device with a battery pack that the patient can wear on a special belt or vest. Artificial hearts are still only a stop‐gap measure, used until the patient can receive a donor heart. When the person’s condition is stable enough for heart surgery to be performed safely, and a donor heart is available, a transplant will be performed and the artificial heart will be removed. Victor Chang’s Artificial Heart Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 HEART TRANSPLANTS People can develop heart failure if their heart muscle has been weakened by coronary heart disease or cardiomyopathy. This damage means the heart can’t pump blood properly. The signs will include breathlessness, tiredness, swelling of the legs and abdomen (fluid build‐up), and electrical disturbances affecting the heart’s rhythm. Not surprisingly, patients lose their ability to exercise. In more advanced cases, the slightest activity can leave people breathless. In the small percentage of severe cases, the only effective treatment is a heart transplant. Once it’s determined that a transplant is the best treatment, the patient will be put on the waiting list for a new heart. But first their kidneys, liver and other organs must be functioning normally; and the patient must be prepared to care for their new heart. No smoking or drinking alcohol again. If a patient fits all the criteria, they’re given a pager so they can be contacted and brought into the hospital as soon as a suitable donor heart becomes available. Surgery normally takes from three to six hours. In most cases, the diseased heart is removed through an incision in the chest and completely replaced with the donor heart. This is known as an ‘orthotopic’ heart transplant. Sometimes the donor heart can be attached to the old heart, as extra pumping power. This is known as a ‘heterotopic’ heart transplant. The patient will normally stay in hospital for just 8 to 10 days after the transplant. Ongoing medical supervision, which needs to be quite frequent at first, is then provided on an outpatient basis. Eventually the patient will only need to come in for an annual check‐up. After surgery most patients will suffer some form of organ rejection, especially in the first six months. Their body recognises the transplanted heart as ‘foreign’ and the immune system tries to ‘reject’ the new organ. To control this rejection effect, the patient will need to take anti‐rejection drugs for the rest of their life. Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 The average heart transplant can last 10 to 20 years and can be performed on people from infancy to 65 years of age, although results are not quite as good in patients over 60. Heart transplant recipients can usually go back to work and lead a normal life. There’s generally no need for them to stick to lighter work. Manual labour and physical pastimes are often still possible. Heart transplant recipients go back to work and can lead a normal life. There is generally no need for lighter work; manual labour and other ‘physical’ occupations are often still possible. Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 HEART FACTS Behind the heart • The word ‘cardiovascular’ comes from the Greek word cardiac, meaning ‘heart’ and the Latin word vasculum, meaning ‘vessel’. The cardiovascular system comprises the heart and blood vessels, arteries, veins and capillaries. • The heart is the first organ to begin functioning in a developing embryo. • Even from before birth, the heart beats relentlessly – around 70 times a minute, 100,000 times a day, two and a half billion times a lifetime. • Each beat pumps between 70 ml and 100 ml of blood. • It takes around 23 seconds for a unit of blood to be pumped from the heart to the lungs, back to the heart, out to the body and back to the heart again. Heart disease in Australia • Despite recent progress, heart disease claims the life of one Australian every 10 minutes1 • Heart disease does not discriminate – it strikes young and old. • About 3.5 million Australians of all ages suffer from some form of heart disease1 Death rates • From 1987 to 2006, age‐adjusted death rates from Cardiovascular Disease fell by 55%3 • However in 2008 heart disease was still the leading cause of deaths in Australia, ahead of all types of cancer and other grouped cause of death – it killed 48,456 people or 34% of all deaths.1 Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 • For a 40 year old, the risk of having coronary heart disease at some time is one in two for men and one in three for women.1 • The health and economic burden of cardiovascular disease (CVD) exceeds that of any other disease in Australia1 Heart disease among women • In Australia, the number of heart failure deaths is 1.7 times higher in women than in men2 • Australian women enjoy an average of 10 to 15 years free of coronary heart disease compared to men – however as a consequence they’re much older than their male counterparts when symptoms develop2 • 10,797 Australian women died from coronary heart disease in 2007, and nearly 25,000 died from some form of cardiovascular disease. That’s 9 times more female deaths than those caused by breast cancer2 • In Australia the life expectancy of women is 83.7 years compared with 79.2 years for men1 Surviving heart disease • Overall survival rates after a heart attack have risen from about 45% in 1997 to over 60% in 2007. However survival rates are much better if the victim gets to hospital quickly – and can reach up to 90% for state‐of‐the art facilities like St Vincent’s Hospital in Sydney. • 50% of heart attack survivors go on to develop heart failure because of the critical loss of heart muscle. • People with a history of CVD account for 5% of the population but 31% of coronary events2 • Each year, around 50,000 Australians have a stroke, with 70% of these being first‐ever strokes1 Heart transplant history • The first heart transplant in Australia was performed at St Vincent’s hospital in 1968 • The first heart‐lung transplant was performed at St Vincent’s Hospital in 1986 Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 • Australia’s first single lung transplant was performed in 1990, and the first bilateral lung transplant in 1992. • There are currently over 3,000 children, teenagers and adults desperately waiting for heart, kidney or lung transplants in Australia References: 1. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2010. Australia’s health 2010. Australia’s health series no. 12. Cat. no. AUS 122. Canberra: AIHW. 2. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2010. Women and heart disease: cardiovascular profile of women in Australia. Cardiovascular disease series no. 33. Cat. no. CVD 49. Canberra: AIHW 3. Australian Institute of Health and Welfare 2010. Cardiovascular disease mortality: trends at different ages. Cardiovascular series no. 31. Cat. no.47. Canberra: AIHW. Victor Chang School Project Material 2012 HEART DISEASE IN CHILDREN ♥ The term ‘congenital heart defect’ means an abnormality of the heart which is present at birth ♥ More than 2,015 babies are born with a heart defect in Australia each year ♥ Heart defects are the most common birth abnormality ♥ Around 1 in 100 babies have a heart defect ♥ More children die from a heart defect than any other birth defect ♥ Up to 20% of heart defects are caused by gene‐linked abnormalities, but what causes the remaining 80% is largely unknown ♥ The severity of heart defects in children can range from a relatively common hole in the heart, to a highly complex combination of conditions ♥ More than half of these conditions are serious enough to require treatment through medication or surgery – some cannot be repaired ♥ It is possible to develop heart conditions like cardiomyopathy and Kawasaki disease during your childhood ♥ There’s no known cure for most heart conditions, so there is an enormous need to develop early intervention strategies for identifying, preventing and treating heart disease in children ♥ Heart disease is the most common reason for Australian children being in hospital intensive care units – with more than 1,300 admissions being admitted each year ♥ Accounting for more than 30% of all infant deaths in Australia, heart disease is our leading cause of infant mortality (0 to 1 years). ♥ Each year, nearly twice as many children die from congenital heart disease as from all forms of childhood cancers combined.