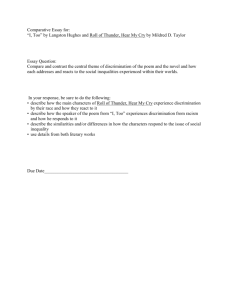

Submission for Consolidation of Commonwealth Anti

advertisement