1 Recurrent Urethral Obstruction Secondary to Urolithiasis in

Recurrent Urethral Obstruction Secondary to Urolithiasis in a Nigerian Dwarf

Goat

Vanessa Bradley, Michigan State University CVM 2014

Case Summary

This case report describes a 4 year old, male castrated Nigerian Dwarf goat diagnosed recurrent obstructive urolithiasis at 20 months of age that was managed both conservatively and surgically over the course of two years with repeated urethral catheterization and three perineal urethrostomy operations.

Introduction

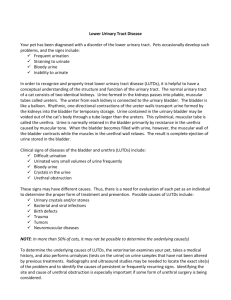

Urolithiasis describes the formation of urinary calculi, and refers to the disease conditions that occur as a result, such as urethral obstruction.

1 Urolithiasis affects many domestic species, including companion and food animals. Urolithiasis is commonly reported in young, castrated male pet goats.

2 Some factors associated with the development of urinary calculi in goats include gender, age at castration, and diet, as well as urine pH and concentration.

2

Urolithiasis is significantly more common in male goats compared to female goats, simply due to the anatomy of the male urethra. In contrast to the relatively short, wide, and straight urethra present in females, the male urethra is long, narrow, torturous, and prone to obstructions, particularly in the sigmoid flexure and urethral process.

2-‐4 The age at which castration occurs also is an important factor in the development of urolithiasis. Early castration results in penile hypoplasia, leading to a decrease in the bore size of the urethra, as well as failure of the urethral process to mature and completely separate from its distal attachment to the preputial mucosa.

2,3 The decreased bore size of the urethra is a major predisposing factor for obstructive urolithiasis.

In addition to anatomical factors, there is considerable research demonstrating that dietary factors also contribute to the development of caprine urolithiasis. Pet goats are commonly fed diets that exceed their caloric requirements, and popular diets often contain alfalfa hay, which is high in calcium, and grains that tend to be high in phosphorus.

9 These diets contain excess minerals,

1

such as calcium and phosphorus that encourage urolith formation.

2,5 Several investigators have created a nutritional model for urolithiasis in various species, and one of these studies demonstrated a higher incidence of urolithiasis in goats fed a diet with increased phosphorus content compared to those fed a diet with a lower phosphorus content 5 . Struvite (magnesium ammonium phosphate) and apatite

(calcium phosphate) uroliths are most common in goats fed high grain diets, which

makes sense as calcium and phosphorus are often fed in excess.

6

In addition to gender, age at castration, and diet, urinary pH and concentration also play a significant role in the formation of uroliths and subsequent development of obstructive urolithiasis. Urinary pH is a major factor in urolith formation – both struvite and apatite uroliths precipitate in alkaline urine.

6,10,16

Stuvite crystals will form at pH 7.2 to 8.4, and apatite crystals will form at relatively more acidic pH range from 6.5 to 7.5 compared to struvite crystals.

7 Urine concentration is another important factor in the development of urolithiasis, as increased urine concentration results in increased precipitation of urinary crystals.

2,6 Urinary concentration can be increased due to decreased water intake, or increased loss of water from the body. During colder months, animals tend to drink less water and thus their urine is more concentrated, increasing the likelihood of urolithiasis. During disease states of increased water loss, risk of urolithiasis is also increased as urine becomes more concentrated due to increased loss or decreased water intake. The body naturally produces urinary crystal inhibitors in the form of colloids that prevent precipitation of crystals, 2,14 and loss of these colloids can result in precipitation and urolithiasis. In addition to urinary crystal precipitation, desquamated epithelial cells can form an excellent nidus for urinary calculi formation.

2 Desquamated epithelial cells are associated with vitamin A deficiency and infections within the bladder.

2,6,8

Diagnosis of urolithiasis in goats is frequently made using signalment, history, and clinical signs alone, though other modalities such as ultrasound, contrast studies, and serum biochemistry can provide additional information that can be particularly valuable to assess the severity of the condition and serve as prognostic indicators.

2,10

2

Signalment is one key that can add obstructive urolithiasis to a list of differential diagnoses. As mentioned previously, castrated males are more commonly affected by urolithiasis than intact males. A retrospective study of 38 cases of caprine urolithiasis had an age range of 2 months to 12 years of age.

27 Many of these animals were obese and essentially all of them received high grain diets.

The same study also found an increased incidence of obstructive urolithiasis in the summer and winter. This may be related to the water balance of the goats – during the winter, urine may be more concentrated due to decreased water intake.

Conversely during the summer, urine may be more concentrated due to increased water loss in the heat. A different retrospective study concluded that pygmy goats were overrepresented in the study population compared to other breeds.

10 The higher incidence of obstructive urolithiasis in pygmy goats may be due to the fact that they are more likely to be kept as pets and thus fed inappropriate, high grain diets as opposed to any genetic factor linked to that breed. As pets, pygmy goats are also more likely to be castrated earlier, and when urolithiasis occurs are more likely to be treated due to the emotional attachment by the owners.

10 A different study reviewing 107 cases of urolithiasis in goats found urolithiasis to be more common in castrated males, and African dwarf breeds.

21

History and clinical signs of urolithiasis vary depending on the degree and location of obstruction, as well as the duration of obstruction.

6 In cases of intermittent obstruction, owners may report a history of clinical signs that wax and wane, depending on degree of obstruction. Early signs clinical signs of obstruction can be relatively nonspecific and include anorexia and lethargy.

2,6 As the disease progresses, clinical signs become more severe and apparent. More advanced signs commonly include stranguria, hematuria, vocalization, tail switching, abdominal distention, restless or anxious behavior, to depression and even recumbency in the advanced stages of obstructive urolithiasis, especially when urethral or urinary bladder rupture occurs.

2,6,10,13 Incomplete obstruction of the urethra can result in complete obstruction due to the inflammation caused to the urethral mucosa by the urolith 6 . Also when stranguria is present, cystitis and ulcerative posthitis must be ruled out, as the clinical signs for those disease processes are similar.

2 In some

3

cases of bladder rupture, an initial improvement in clinical signs may be noted followed by a marked decrease in status as uremia ensues.

2 When goats are severely depressed following rupture, hepatoencephalopathy and enterotoxemia must be ruled out, and confirmation of urine in the abdomen can diagnose urinary bladder or urethral rupture.

2 The progression of clinical signs vary, but one retrospective study reported the median duration of clinical signs prior to admission to be 30 hours.

10 If obstruction is not treated, urinary bladder or urethral rupture can occur in 24 – 48 hours.

2 The entire clinical course of obstructive urolithiasis can last 2 – 5 days from onset to death if appropriate medical or surgical intervention does not occur.

2

The physical exam is often a key component of the diagnosis of urolithiasis in goats. In addition to vital signs, thorough evaluation of the prepuce and palpation of the urethra are key in the diagnosis of obstructive urolithiasis.

2,6 The physical exam can easily reveal obstructions of the urethral process and distal urethra through extrusion of the penis.

6 A supportive sign of urolithiasis is the presence of crystals on the preputial hair, and signs of sensitivity or pain on urethral palapation.

6 In cases of urinary bladder rupture, bilateral ventral abdominal distention may be noted, and abdominocentesis can confirm the presence of urine in the abdomen.

6 If the urea nitrogen or creatinine concentrations in the peritoneal fluid is equal to or greater than those concentrations in the blood, then the fluid is urine.

2 Urethral rupture can also result in subcutaneous edema near the prepuce.

6

Clinical pathology findings will vary depending on the duration of the urinary obstruction. Common abnormalities include azotemia, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, and hypokalemia.

6 More severe derangements are seen in cases of rupture or obstruction of longer duration.

6 A retrospective study of 107 cases of goats with uroliths found that they were frequently hypophosphatemic at admission, and hypochloridemic metabolic alkalosis was the most common acid-‐ base abnormality.

21 In cases with urinary bladder or urethral rupture, hyponatremia and hyperkalemia were more common.

21

Additional diagnostic modalities include contrast radiography, ultrasonography, and endoscopy. Contrast studies can aid in determining the

4

location of an obstruction within the urethra, and rule out bladder rupture.

2,20

Urethral calculi are not always detected on survery radiographs, 14 limiting its use as a key diagnostic tool. Ultrasonography is a rapid, minimally invasive method to determine the extent calculi, and also detect free abdominal fluid that may be indicative of urinary bladder rupture, which can be important in the decision of the appropriate treatment strategy.

2,10 Urethral endoscopy can also be used to both evaluate urethral patency, and provide information regarding long-‐term prognosis by evaluating the urethral mucosa following relief of the obstruction.

14 Normograde cystourethrography has also been used to monitor urethral patency following tube cystotomy by inserting the contrast medium through the tube into the bladder in pigs and small ruminants.

20 Survey radiographs and excretory urography both have limited use in the diagnosis and management of urethral urolithiasis in pigs and small ruminants.

20

Arriving at a diagnosis of obstructive urolithiasis is relatively easy, however selecting the best treatment modality can be much more difficult. Treatment options for urolithiasis include medical and surgical management. In general less severe cases with incomplete obstruction are more likely to be managed successfully medically, compared to cases of more severe obstruction, which often require more aggressive surgical treatment.

2,6 Numerous studies have found that medical treatment in combination with urethral process amputation is not effective long term, and only provides temporary relief as reobstruction is likely.

2,6,10,13

When choosing a treatment modality, the patient’s intended use should be taken into consideration. For example, the surgical treatment for breeding goats that best suits continued productivity is location and removal of the urolith.

2 It has been suggested that if an animal is to be used for breeding, then surgical tube cystotomy is the best choice, but if the animal is a pet and urethral patency is not required, bladder marsupialization is the better option.

10 All treatment modalities have benefits and complications associated with them, so selection is based on long-‐ term goals for the individual patient and the owner’s ability and willingness to finance and provide aftercare for the treatment.

5

The location of the obstruction is also taken into consideration when selecting the treatment. For example, if the obstruction is present in the urethral process, amputation of that process may be therapeutic so long as other obstructions are not present.

2 If the obstruction is proximal to the urethral process, passing a urinary catheter for retropulsion may alleviate the obstruction, 2 but other surgical treatment options may be more effective to prevent reobstruction.

Regardless of the treatment modality selected, the most important component is the correction of fluid and electrolyte abnormalities.

2,6 Correction requires intravenous fluid administration, which carries the risk of increased bladder distention and rupture – however this is preferred to taking an unstable animal to surgery.

10,12,13,19 During fluid resuscitation, a percutaneous catheter can be placed into the bladder lumen to prevent bladder rupture while stabilizing the animal before surgery.

14 This is the desirable alternative to repetitive cystocentesis, as that increases the risk of peritonitis and vesicular-‐intestinal adhesions.

15

Medical treatment options for obstructive urolithiasis include dietary modification, addition of urine-‐acidifying agents to the diet, Walpoles solution, and retropulsion. Retropulsion in ruminants is not as successful as it is in other domestic species due to the presence of the urethral diverticulum.

10,11 The urethral diverticulum also makes it difficult to pass urinary catheters into the bladder, and also difficult to retropulse urethral calculi. If retropulsion is attempted, tranquilizers and antispasmodics should be used for the comfort of the goat, and to encourage a successful outcome of the procedure.

2 Therefore dietary modification and addition of urine-‐acidifying agents, such as ammonium chloride, and to the diet are more commonly used for the conservative treatment of obstructive urolithiasis in goats.

Dietary modification and addition of urine acidifying agents such as ammonium chloride to the goat’s diet have been shown to be effective in the prevention of recurrent obstructions, and are an important component of both medial and surgical treatment.

2,4,6,16 A high roughage diet composed of alfalfa and mixed grass hay without grain is a popular dietary recommendation for goats

6

affected by urolithiasis.

2,6 Adding ammonium chloride will decrease urine pH, and can prevent the formation of struvite and apatite crystal formation.

16

Walpole’s solution is composed of sodium acetate (1.16%), glacial acetic acid

(1.09%), and distilled water (97.75%) and has a pH of 4.52.

5 This solution has been used to dissolve struvite calculi in numerous species, and was investigated for use as a treatment for urolithiasis in male goats in retrospective case study series.

25 In this study, Walpole’s solution was injected into the bladder using ultrasound guided percutaneous infusion of 50ml – 250ml of solution to reach target urine pH of 4 to 5.

To reach the target pH, the solution was administered once in 72% of goats, twice in

24% of goats, and three times in 4% of the goats. Of the 25 male goats in the study, urethral obstruction was resolved in 80% of the goats, and the remaining 20% were euthanized due to unresolved urethral obstruction and the owners declining surgery. However, 30% of the goats that were discharged returned at a later date due to the recurrence of urethral obstruction. In addition to administration of

Walpole’s solution, the urethral processes were amputated if still intact, and ammonium chloride was administered in 84% of the cases. The hospitalization time for these goats ranged from 0.5 to 8 days. The most common complication noted with this procedure was leakage of urine from the puncture sites in the urinary bladder. Walpole’s solution is known to be irritating to mucous membranes, and goats that were euthanized and underwent necropsy had signs of cystitis, but it is unclear whether Walpole’s solution caused the cystitis or if it was pre-‐existing.

25

Surgical treatments are next in line when conservative treatment fails. As previously mentioned, it is imperative to stabilize patients prior to surgery by correcting fluid and electrolyte imbalances.

2 Traditional surgical treatment options include urethral process amputation, percutaneous or surgical tube cystotomy, perineal urethrostomy(PU), and bladder marsupialization. Recently, laser lithotripsy has been safely and effectively used in three goats to treat calculi lodged in the urethra.

14

Though urethral process amputation is technically a surgical procedure, it is commonly considered part of medical or conservative management of obstructive urolithiasis as it is a relatively quick and simple procedure, and is often one of the

7

first treatments performed. However, the relief provided is only temporary, and 80-‐

90% of cases will reobstruct within hours to days.

13

Percutaneous tube cystotomy can be used to avoid general anesthesia in high risk patients, but has a higher complication rate compared to surgical tube cystotomy and bladder marsupialization.

10,12 One retrospective study found that

50% of patients had catheter displacement that required a second procedure, compared to 12% of surgical tube cystotomy patients.

10 The marked difference is likely present because during the surgical tube cystotomy procedure, the catheter was secured in the bladder with a suture, which was not possible using the percutaneous method.

10 Another common complication found was adhesions with percutaneous and surgical tube cystotomy between the small intestines and bladder in the goats that required a second surgical procedure following percutaneous tube cystotomy.

10,12

Surgical tube cystotomy is one of the procedures used for long-‐term treatment of obstructive urolithiasis in goats, and may be the best surgical option for breeding animals and pets for long-‐term success.

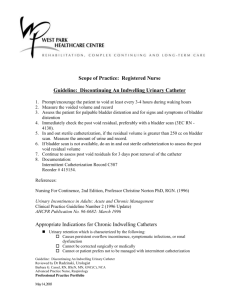

10,12 Ewoldt et al 10 performed a retrospective clinical study evaluating the short and long term outcome of tube cystotomy without urethral flushing in small ruminants. The operation was completed under general anesthesia through a paramedian incision lateral to the prepuce halfway between the scrotal base and preputial orifice. The urinary bladder was located and isolated, and a cystotomy was performed near the apex of the bladder to evacuate urine and debris. A Foley catheter (size dependent upon animal, usually 18-‐20 French) was inserted through a stab incision 4 -‐10 cm paramedian from the celiotomy incision, and then was secured in the ventrolateral aspect of the bladder on the same side as the celiotomy incision, and was secured using a purse string suture. The catheter was used to pull the bladder close to the body wall, was secured to the skin using a Chinese finger trap suture. The external end of the Foley catheter was left uncovered. Potential complications of leaving catheter in place are catheter obstruction and accidental removal, neither of which were a problem in the present study, but have been reported in previous studies.

12

Urethral patency was determined after 7 days of free drainage by intermittently

8

occluding the Foley catheter with a clamp. If animals showed signs of discomfort, the clamp was removed. Once the animals remained comfortable with the clamp in place for 24-‐48 hours, the Foley catheter was removed. The mean time to normal urination following the procedure was 11 + 8 days, which may have been affected by the tubes not being clamped until seven days after the procedure, as normal urination is difficult to produce before the tube is clamped. This study reported 76% of all animals were successfully treated by the time of hospital discharge. Of the animals discharged, 90% were successfully treated by tube cystotomy. At six months follow up post-‐surgery, 46% did not have any recurrence of clinical signs, and 70% were still alive. Complications of tube cystotomy include failure to relieve obstruction, peritonitis, adhesions, urethral rupture, and catheter dislodging or clogging with debris from the environment or from the bladder itself (blood, calculi,

“sludge”).

10,15 Plugged catheters could often be managed by gentle retrograde flushing 10 , but other complications required additional surgery. One study conducted by Fortier et al 10 found 52% of goats necessitated a second surgery due to complications of tube cystotomy. One drawback to this procedure is the amount of hospitalization required afterwards, which may be limiting due to owner’s finances.

20

A retrospective study on the outcome following tube cystotomy in small ruminants reported a lower rate of reobstruction than previous studies, and attributed that in part to dietary changes recommended at the time of discharge.

The researchers recommended the drastic reduction or elimination of grain in the diets, increased grazing, and grass hay as opposed to alfalfa hay. Feeding ammonium chloride was also recommended.

10

In pets, a perineal urethrostomy (PU) is a salvage procedure, 2 as breeding ability is lost in intact males. There are some slight variations in this procedure, and it will be described as performed by Haven et al (1992). This procedure is performed under general anesthesia. A midline incision is made over the penis just ventral to the ischiatic arch. A short segment of penis is bluntly dissected to free it from surrounding tissues so that an incision can be made into the urethra through the urethral muscle and corpus spongiosum. The urethra is then transected distally,

9

and that end is sutured to the subcutaneous tissue and skin of the initial incision.

This provides a larger urethral opening that will allow large calculi to pass without causing and obstruction. Disadvantages of PU for treatment of obstructive urolithiasis include loss of breeding ability in intact males and poor long-‐term results 13 . Often pet goats are castrated, so loss of breeding ability is not an issue. In cases of urethral rupture, primary closure of the urethra is rarely an option and second intention healing is usually the sole option.

15 During this time, urine must be diverted from the urethra via tube cystotomy or bladder marsupialization.

15

Perineal urethrotomy (PU) and urethrostomy are associated with poor long term outcomes due to stricture formation, resulting in recurrent obstruction.

10,13

One retrospective study examined the efficacy of PU versus cystotomy with normograde and retrograde flushing, and concluded that cystotomy in combination with appropriate dietary management following surgery produced better long term results compared to PU alone.

13 The authors did believe a PU may be indicated when urethral rupture was eminent, or the obstruction could not be relieved by flushing attempts.

13

As stricture formation is a common complication in PU operations, prepubic urethrostomy is a secondary operation that can be used to relieve urinary outflow obstruction from the stricture formation.

24 However, this surgical procedure can be quite involved – one case study described the procedure in a sheep that required pubic osteotomy to achieve appropriate urethral exposure, but this was not required in a goat with the procedure.

24 Essentially, the urethra is diverted from the perineal site to the caudal ventral abdomen. Urinary continence is maintained, but one complication is ascending urinary tract infections. Both animals showed evidence of ascending urinary tract infection following this procedure, and the goat was euthanized due to stricture formation at the new site.

Bladder marsupialization is another surgical option that is typically a one-‐ time procedure, thus shortening hospital time and expense, 10 and was originally used as a salvage procedure when financial constraints were present.

22 The success rate for this procedure has been reported to be 80%.

22,23 In a retrospective study of

19 goats receiving bladder marsupialization as treatment for obstructive

10

urolithiaisis, 22 seven goats had urethrostomy previously, and one had three cystotomies in conjunction with urethrostomies, so the bladder marsupialization was used as a salvage procedure in this case. This procedure is typically performed under general anesthesia, using two paramedian incisions. The first incision is used to locate the bladder and bring it to the ventral body wall for cystotomy, and the second incision is used as the marsupialization site. The bladder is secured to the site by suturing the seromuscular layer of the bladder to the abdominal fascia at the incision, followed by suturing the cystotomy margins to the skin. One complication that has been reported in virtually all patients after bladder marsupialization is urine scald, however the owners still remain satisfied with the procedure.

22,23 Other complications encountered with bladder marsupialization include cystitis, ascending urinary tract infection, and bladder mucosal prolapse.

22,23 One recent case study reported success using a laparoscopic surgical technique to perform bladder marsupialization on a goat that had recurrent urethral obstruction following perineal urethrostomy.

26 The authors reported minimal signs of postoperative pain, and conclude that the laparoscopic technique as a sound alternative to traditional laparotomy techniques for bladder marsupialization.

Postoperative complications still included urine scald, just the same as other marsupializations – but recovery postoperatively was quicker and with less pain as perceived by the authors.

The prognosis for goats with obstructive urolithiasis varies depending on the severity of the obstruction, and treatment selected. In general, prognosis remains fair to guarded as recurrence is likely. If conservative treatment fails, then long-‐ term prognosis is guarded to poor.

2 One retrospective study found that serum potassium concentration <5.2 mg/dL, no fluid in abdomen and intact urethral process at time of admission were associated with a higher likelihood of survival.

10

The same study concluded that prognosis for survival following tube cystotomy was good, up to several years. The reason long term prognosis is poor is most often due to the incomplete clearance of calculi within the urethra, and stricture formation in the urethra due to irritation and pressure necrosis that results in recurrent obstruction.

14 A retrospective study reviewing 45 cases of male goats with

11

obstructive urolithiasis compared percutaneous tube cystotomy, surgical tube cystotomy, and bladder marsupialization as treatment options, and found that there was not any difference between the three treatments for time to mortality, but that percutaneous tube cystotomy was associated with more complications and need for a second intervention compared to the other two procedures.

12 It has also been reported that the presence of free abdominal fluid and intact urinary bladders is poorly correlated with successful outcome after tube cystotomy.

12 This may be due to the longer duration of obstruction resulting in leakage of fluid from the bladder, and perhaps more pronounced electrolyte abnormalities.

12

Obstructive urolithiasis is a serious problem that commonly affects pet goats.

Once the urolithiasis occurs, it is difficult to manage, so prevention is key. Dietary management is likely the most important method to prevent recurrence of urolithiasis. Pet goats should receive high quality, free choice mixed alfalfa and grass hay with salt and trace minerals.

2 Water should be available at all times in excess to encourage increased urine volumes.

2 The calcium phosphorus ration should be 2:1 to 2.5:1.

2 In one clinical trial, ammonium chloride administered to male castrated yearling goats at a dose of 450mg/kg or 2.25% of DMI resulted urine pH of <6.5 for 24 hours.

16 These goats were being fed orchard grass hay, so the results of ammonium chloride administration may be different with other diets.

Ammonium chloride is unpalatable, resulting in decreased owner compliance, as it is more difficult to encourage goats to consume this supplement.

16 Side effects of ammonium chloride supplementation in goats have not been documented, however osteopenia has been reported in sheep with dietary-‐induced metabolic acidosis, 17 and in dogs and cats it has been shown to increase urinary calcium concentration.

18,19 Fractional excretion of calcium was increased in goats being treated with ammonium chloride in the clinical trial, but the authors believe that the decreased urine pH due to the increased urinary chloride excretion may offset the risk of calcium carbonate urolith formation due to the acidic pH.

16

Delaying castration is also another preventive strategy, however breeding can occur at 3 months of age so this is not always practical from a management

12

standpoint.

2 Therefore, dietary management is key to prevent future obstructive urolithiasis.

Case Report

The patient presented as a 20-‐month-‐old castrated Nigerian Dwarf goat with a one-‐day history of stranguria. Prior to presentation, the referring veterinarian amputated the urethral process and passed a urinary catheter, but obstructive uroliths were not visualized, and the patient continued to strain. The referring veterinarian performed serum chemistry revealing normal creatinine, BUN, sodium, potassium and chloride values, whereas phosphorus was decreased (2.8 mg/dL; reference range 4.2 – 7.6).

On presentation , the patient’s vitals were within normal limits. Packed cell volume (PCV) and total solids (TS) were 35% and 6.6 g/dL, respectively. A venous blood gas revealed azotemia, hyperglycemia, and a normochloremic metabolic alkalosis. Ionized calcium was decreased, and lactate was mildly elevated. The azotemia likely had both pre-‐ and post-‐renal components, as the patient had evidence of a urinary obstruction, and was assessed to be moderately dehydrated as well. Hyperglycemia was likely to due stress. The most common acid-‐base abnormality in these cases is hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis.

21 It is possible that the duration of obstruction in this case was not long enough to see the decreased chloride levels. The decreased calcium is associated with urinary tract obstruction, but the pathogenesis is not clearly understood.

28 The slight elevation in lactate may have been due to tissue damage and ischemia secondary to urinary obstruction.

Survey radiographs were performed at admission, but did not reveal any radiopaque stones. The patient was sedated with diazepam, and a n ultrasound guided percutaneous bladder catheter was placed to relieve the pressure caused by the suspected obstruction. Once the catheter was in place, a large amount of sanguineous fluid with sediment was drained through the catheter. Intravenous fluid therapy was started using Lactated Ringer’s Solution (LRS) at a rate of 250 mL/hr. The patient was prescribed Naxcel (2.2 mg/kg) subcutaneously every twelve hours in case of secondary urinary tract infection, and Banamine (25 mg IV)

13

every twelve hours for the first day, to be decreased to once daily thereafter as needed for analgesia .

The following morning , the patient’s vitals were stable, and urine was draining freely from the catheter. Blood glucose and lactate were re-‐evaluated at this time and found to be in the normal reference range. PCV and TS decreased

(30% and 6.2 g/dL respectively), likely due to hemodilution secondary to fluid therapy. At this time the plan was to monitor the patient’s catheter to ensure urine continued to drain freely for two days, then attempt clamping the catheter to assess

the patient’s ability to urinate normally.

The patient remained stable during those two days and urine drained freely from his catheter. When the urinary catheter was clamped, the patient strained to urinate, and the catheter was unclamped later that same day due to the distention of his urinary bladder. Urine dipstick test revealed a pH of 8.5, and large amounts of blood . The decision was made to delay discharge to allow his urethra to heal.

Ammonium chloride (10 grams PO SID) was added to his treatment protocol to acidify his urine with the goal of dissolving uroliths currently present in his urinary

bladder, and preventing the formation of new ones.

For an additional three days, the patient was managed with the percutaneous urinary catheter. Banamine was discontinued on the second day. The patient’s vitals remained stable, and his urine pH decreased to 6.0 over this period of time, indicating a positive response to the ammonium chloride. The catheter was again clamped on the third day to evaluate the p atient’s ability to urinate on his own, and once again he strained and the catheter had to be unclamped to allow his bladder to drain. At this time, surgical options (perineal urethrostomy and bladder marsupialization) were discussed. The patient was given an additional three days with the unobstructed percutaneous catheter to encourage urethral healing. During this time his urine pH remained at 6.0, but when the catheter was capped once again the patient strained to urinate, and the decision was made to perform the perineal urethrostomy.

On the eleventh day of the patient’s hospitalization, a perineal urethrostomy

(PU) was performed without immediate complications. The percutaneous catheter

14

was clamped the evening of the surgery, and trace amounts of diluted blood and urine drained from red rubber catheter in the patient’s urethra the following morning. The patient’s vitals remained stable, and he was noted to have an excellent appetite following the surgical procedure. Naxcel and ammonium chloride were continued at the same dosages. The percutaneous catheter was removed the day following the PU operation, and no complications were noted. The red rubber catheter was removed from the patient’s urethra on the second day following surgery, and the patient was monitored to confirm normal urination without blood before he was discharged from the hospital.

The patient was discharged on the fifth day following his PU. At this time, the owners were educated regarding the dietary changes necessary to prevent future obstructive calculi from forming. The owners were instructed to feed a high roughage diet composed of good quality alfalfa/grass hay and provide access to fresh water at all times. Trace minerals were recommended to increase the patient’s thirst and encourage him to drink more water. Ammonium chloride (10 grams SID) was prescribed for maintenance of lower urine pH. At the time of discharge, the patient’s penile stump occasionally dripped some bloody discharge but his urination was normal.

A recheck examination was performed approximately one month following the patient’s discharge, and the PU site was healing appropriately. The owners reported the patient was urinating normally at that time.

The patient presented three months following the PU for progressive stranguria.

T he patient was bright, alert, and responsive with normal vitals with the exception of panting. The patient was dripping and spraying a fine mist of urine from his urethrostomy site that was 7/8ths obstructed due to stricture from scar tissue formation at the site. Ultrasonographic examination revealed a severely distended bladder. The patient was sedated with xylazine, and a “Tom Cat” urinary catheter was passed with 4 mL of lidocaine through the PU site into the bladder.

190 mL of urine was evacuated using a 60 mL syringe, followed by passing the smallest Foley catheter and aspirating an additional 60 mL of urine. Finally the second smallest urinary catheter (5 french) was passed through the PU site into the

15

bladder, and was tacked with 4-‐0 suture to be removed in four days. The patient was hospitalized for a total of four days. On the day prior to discharge, the PU site was opened using scissors following application of local anesthetic, and the sutures holding the catheter in place were reinforced. Patient was given a dose of Nuflor

(900 mg) to provide four days of antibiotic coverage in case of infection. The patient remained stable during this time, and the catheter was removed four days following discharge as directed.

One week following removal of the catheter, the patient re-‐ presented with stranguria once more . The patient was anesthetized with isofluorane, and a “Tom

Cat” catheter was placed, sutured, and Patient was sent home. Over the course of the next six months, the stricture at the PU site was managed by replacing urinary catheters under general anesthesia, using the largest bore size that would fit through the stricture. Nine catheters were used over the course of six months, but the stricture remained. Approximately nine months following the first PU it was decided a second PU operation was necessary and the owners consented.

The patient’s PU revision occurred approximately 9 months following the original operation. During the operation, the penis was brought more superficially and sutured to more superficial subcutaneous tissues compared to the previous operation in hopes of preventing stricture formation. The surgery was performed with only minor hemorrhage following incision into the urethra that was controlled later with compression and ice packs. The site was rechecked two weeks following the procedure, and was noted to be healing well at that time.

Three months following the PU revision (1 year after first PU), the patient presented with a two hour history of stranguria. On physical exam, the patient’s pulse and respirations were mildly elevated, and dripping urine was noted from his

PU site. Patient was anesthetized to allow placement of a urethral catheter to check for obstructing calculi, but none were discovered. There was not any evidence of stricture formation either, so cystitis was the presumed diagnosis and the patient was treated accordingly with Naxcel (2.2mg/kg) administered subcutaneously twice daily for five days.

16

Five days later, the patient presented to the hospital again for decreased urine flow and stranguria. The day before presentation the owners noticed the patient had a depressed attitude. The patient had been receiving ammonium chloride twice daily, but was receiving 5-‐ 6 grams once daily for a period of time, and again increased to twice daily prior to presentation as reported by the owners.

During this time he was being fed grass hay and no grain. On physical exam, the patient’s pulse and respirations were markedly elevated (192 beats/min and 72 breaths/min). The patient was actively straining to urinate while standing.

Ultrasound exam of the bladder revealed a dilated bladder (about 6.5 cm) with sludge sitting on the ventral aspect. At this time, the patient was placed under general anesthesia, a catheter was passed, and his bladder was flushed with 2 liters of sterile saline.

Six months later, the patient presented to the hospital due to inability to urinate for one day. The owners reported the patient had been recently moved to a new pasture, and did not drink as much as usual, perhaps due to the new surroundings. The patient’s bladder was flushed at the hospital the previous day, and he returned due to lack of improvement. On physical exam the patient’s vitals were within normal limits, and he was dribbling urine. Ultrasound exam revealed a distended urinary bladder, approximately 13 cm in diameter. On dipstick exam, urine pH was 6.0 with large amounts of blood present. Glucose was negative.

Abdomen was tense on abdominal palpation. A venous blood gas revealed mild acidemia with metabolic acidosis, mild hyponatremia and hyperchloremia. PCV and

TS were 38% and 6.5 g/dL, respectively. The urine specific gravity was 1.010, and the culture and susceptibility results indicated a gram postitve cocci. A urethral catheter (5 French) was placed under general anesthesia, and the urethra and bladder were flushed with saline. The following day, a larger catheter (8 French) was placed and the urethra and bladder were infused with Walpole’s solution to decrease urinary pH and dissolve the uroliths present in the bladder . Ultrasound exam that day revealed a smaller bladder with debris floating inside. Urine pH was reduced to 5.0 after the infusion of Walpole’s solution. The bladder size on ultrasound the following day was still small, with improvement of the amount of

17

debris in the bladder. During his hospitalization, the patient received 37.5 mg of

Banamine IV, Naxcel (2.2 mg/kg) SQ, and 8 grams of ammonium chloride PO daily.

Salt slurries were administered as needed to encourage thirst. Before discharge

(four days after admission), the patient also received a dose of Excede (200 mg) to treat the urinary tract infection that was to be repeated in four days. The discharge instructions to the owners emphasized the importance of daily administration of 8 grams of ammonium chloride for the remainder of the patient’s life. The urinary catheter was to remain intact for 3-‐5 days before removal.

Two days following discharge the patient returned to the hospital unable to urinate. On presentation, he was panting and excessively vocalizing. Again, ultrasound revealed a distended bladder, so he was anesthetized and his urethra and bladder were catheterized. A calculus was identified in the urethra, but several attempts were unable to remove the stone. A red rubber catheter to allow urine outflow that was to remain in place for 8-‐10 days. Patient was prescribed Excede

(200 mg SQ once daily) for four days, and the continuation of ammonium chloride (8 grams PO SID) administration. The patient stayed in the hospital for two days, then returned home once more.

Approximately ten days later the patient returned to the hospital with stranguria and hematuria as the presenting complaint. The urethral catheter was slipping out, and had to be shortened as a result. The hematuria was present for approximately five days prior to presentation, but the patient’s attitude and appetite remained normal. Vital parameters were within normal limits, with the exception of a slightly elevated pulse. On physical exam, Patient was straining and drips of urine were coming from the catheter. PCV and TS were 30% and 7.0 g/dL respectivley.

The patient’s third PU was performed under general anesthesia to relieve the obstruction in his urethra. The patient received Banamine (40 mg SQ/IV twice daily) for the first two days following the operation to control pain. Excede was also administered (200 mg SQ), and was to be repeated every four days for two additional doses. Patient was discharged with the same instructions to the owners regarding dietary management of urolithiasis to prevent future reobstructions.

18

Three days following the operation, the patient presented due bleeding from his PU site. The owners first noted the patient urinating in a split stream without any blood or straining, then on the morning five days following the operation the owner noted bleeding near the incision site that did not stop, and ranged from drops to a steady stream of blood. On presentation, his hind end was covered in blood, and blood clots were present from near the incision site to both hind limbs. The surgeon inspected the site, and found the patient to be quite painful near his tail, and located an arterial bleeder near the incision site. The surgeon determined the site itself was intact, and a 10 French catheter was easily passed, indicating a patent urethra. To slow the bleeding, silver nitrate sticks were applied to the area. The patient was hospitalized for a total of six days. PCV and TS were monitored during this time. The values at admission were 30% and 5.8 g/dL, and decreased to 15% and 5.5g/dL on day four of hospitalization, the same day in which the bleeding from the artery started again. The patient was placed under general anesthesia for periurethrostomy artery ligation, which was successfully completed. At this time, buccal mucosal bleeding time (BMBT) was assessed and found to be within normal limits, indicating normal primary hemostasis. Following the operation, Patient received Banamine for pain management, and Excede to prevent infection. On the sixth day, the patient was discharged from the hospital urinating normally.

The patient returned to the hospital approximately two months following his third PU operation for suture removal. The owner reported that the patient was doing very well at home, had a great appetite, and was urinating normally without any difficulty. After the sutures were removed from the PU site, the patient was sent home without any further treatment necessary.

This case illustrates the long, difficult management of obstructive urolithiasis in pet goats. The owners of this goat were exceptional in the amount of time and finances they allotted to the treatment of this problem—this is not typical of many cases. It is of the opinion of the author that repeat perineal urethrostomy or bladder marsuplializaiton earlier in the course of the disease may have been appropriate once stricture formation became an issue as opposed to repeat catheterizations in an attempt to manage the stricture formation. PU revision does not guarantee the

19

abolishment of stricture formation, but may have been more effective than catheterization. Bladder marsupialization was another option for this patient in response to stricture formation. However, urine scald is a postoperative complication that affects relatively all cases and would have to be accepted and managed by the owner. The relapse in the patient’s condition that occurred after his water consumption and ammonium chloride dose was temporarily decreased clearly demonstrated the importance of dietary management in the face of obstructive urolithiasis – regardless of the surgical or medical procedures performed, obstruction will reoccur if diet is not managed properly.

Obstructive urolithiasis is a common, difficult problem in pet goats.

Preventive dietary management should be encouraged to those owners to prevent

this disease process, as it has such a poor long-‐term prognosis once it is initiated.

20

References

1.

R. Connel, F. Whiting, and S. A. Forman Silica Urolithiasis in Beef Cattle

Observation on Its Occurrence. Canadian Journal of Comparative Medicine

1959;23:41 – 46.

2.

Smith MC, Sherman DM. Urinary System. In: Cann CG ed, Goat Medicine.

Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger,1994;398 – 402.

3.

Kumar RK et al. Effect on castration on urethra and accessory sex glands in goats. Indian Vet J 1982;59:304–308.

4.

Van Metre D, House J, Smith B, et al. Obstructive urolithiasis in ruminants: medical treatment and urethral surgery. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet

1996;18:317–327.

5.

Sato H, Omori S. Incidence of urinary calculi in goats fed a high phosphorus diet. Jap J Vet Sci 1911;39:531–537.

6.

Jones ML, Miesner MD. Urolithiasis. In: Merchant T ed, Food Animal Practice

5 th ed. St Louis: Saunders, 2009;322–325.

7.

Elliot JS, Quaide WL, Sharp RF et al: Mineralogical studies of urine: the relationship of apatite, brushite and struvite to urinary pH, J Urol 1958;

80:269-‐271.

8.

Packett LV, Coburn SP: Urine proteins in nutritionally induced ovine urolithiasis. Am J Vet Res 1965;26:112-‐119.

9.

Pond WG, Church DC, Pond KR, Schoknecht PA. Sheep and Goats. In:

Raphael C, Wolfman-‐Robichaud S eds, Basic Animal Nutrition and Feeding.

Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2005;439-‐461.

10.

Ewoldt JM, Anderson DE, Miesner MD, Saville WJ. Short-‐ and Long-‐Term

Outcome and Factors Predicting Survival After Surgical Tube Cystotomy for

Treatment of Obstructive Urolithiasis in Small Ruminants. Veterinary

Surgery 2006;35:417–422.

11.

Garrett PD. Urethral recess in male goats, sheep, cattle, and swine. J Am Vet

Med Assoc 1987;191:689–691.

12.

Fortier LA, Gregg AJ, Erb HN, et al: Caprine obstructive urolithiasis:

Requirement for 2nd surgical intervention and mortality after percutaneous

21

tube cystostomy, surgical tube cystostomy, or urinary bladder marsupialization. Vet Surg 2004;33:661–667.

13.

Haven ML, Bowman KF, Englebert TA, Blikslager AT. Surgical management of urolithiasis in small ruminants. Cornell Vet 1993; 83:47-‐55.

14.

Halland SK, House JK, George LW. Urethroscopy and laser lithotripsy for the diagnosis and treatment of obstructive urolithiasis in goats and pot-‐bellied pigs. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2002;220:1831 – 1834.

15.

Rakestraw PC, Fubini SL, Gilbert RO, et al: Tube cystostomy for treatment of obstructive urolithiasis in small ruminants. Vet Surg 1995;24:498–505.

16.

Mavangira V, Cornish JM, Angelos JA. Effect of ammonium chloride supplementation on urine pH and urinary fractional excretion of electrolytes in goats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2010;237:1299-‐1304.

17.

MacLeay JM, Olson JD, Enns RM, et al. Dietary-‐induced metabolic acidosis decreases bone mineral density in mature ovariectomized ewes. Calcif Tissue

Int 2004;75:431–437.

18.

Ching SV, Fettman MJ, Hamar DW, et al. The effect of chronic dietary acidification using ammonium chloride on acid-‐base and mineral metabolism in the adult cat. J Nutr 1989;119:902–915.

19.

Sutton RA, Wong NL, Dirks JH. Effects of metabolic acidosis and alkalosis on sodium and calcium transport in the dog kidney. Kindney Int 1979;15:520–

533.

20.

Palmer JL, Dykes NL, Love K, Fubini SL. Contrast radiography of the lower urinary tract in the management of obstructive urolithiasis in small ruminants and swine. Veterinary Radiology & Ultrasound 1998;39:175-‐180.

21.

George JW, Hird DW, George LW. Serum biochemical abnormalities in goats with uroliths: 107 cases (1992-‐2003). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2007;230:101-‐

106.

22.

May KA, Moll HD, Wallace LM, et al: Urinary bladder marsupialization for treatment of obstructive urolithiasis in male goats. Vet Surg 1998;27:583–

588.

22

23.

May KA, Moll HD, Duncan RB, et al: Experimental eval-‐ uation of urinary bladder marsupialization in male goats. Vet Surg 2002;31:251–258.

24.

Stone WC, Bjorling DE, Trostle SS, Hanson PD, Markel MD. Prepubic urethrostomy for relief of urethral obstruction in a sheep and a goat. J Am

Vet Med Assoc 1997;210:939-‐941.

25.

Janke JJ, Osterstock JB, Washburn KE, Bisset WT, Roussel Jr AJ, Hooper RN.

Use of Walpole’s solution for treatment of goats with urolithiasis: 25 cases

(2001 – 2006). J Am Vet Med Assoc 2009;234:249-‐252.

26.

Hunter BG, Huber MJ, Riddick TL. Laparoscopic-‐assisted urinary bladder marsupialization in a goat that developed recurrent urethral obstruction following perineal urethrostomy. J Am Vet Med Assoc 2012;241:778–781.

27.

Craig, DR, Stephan M, Pankowski RL. Urolithiasis: A retrospective study in sheep and goats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1987;190:1609.

28.

Stockham SL, Scott MA. Calcium, Phosphorus, Magnesium and Regulatory

Hormones. In: Stockham SL, Scott MA eds, Fundamentals of Veterinary

Clinical Pathology, 2 nd ed. Ames: Blackwell Publishing, 2008;593-‐638.

23