Examiners' commentaries 2014 - University of London International

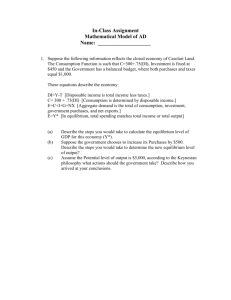

advertisement