Laptop Report - FINAL w_all

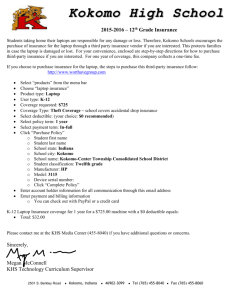

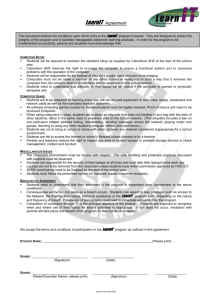

advertisement