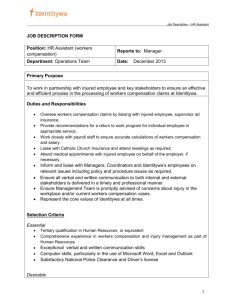

Compensation and Employee Misconduct

advertisement