Reporting - Inspector General

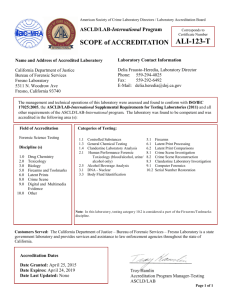

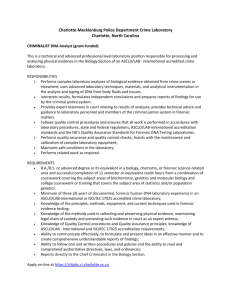

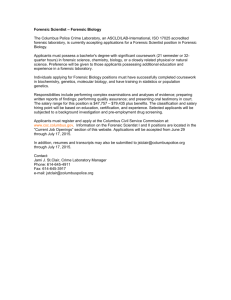

advertisement