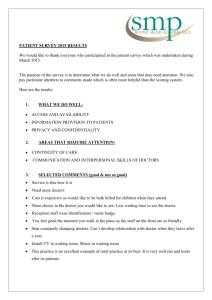

Talking abouT good professional pracTice

advertisement