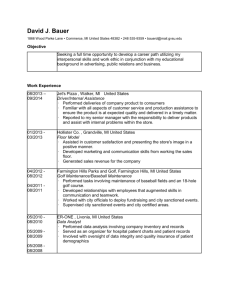

advertising - Core Media

advertisement