Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2012) 889–897

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Computers in Human Behavior

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/comphumbeh

The effect of online privacy policy on consumer privacy concern and trust

Kuang-Wen Wu a,1, Shaio Yan Huang b,2, David C. Yen c,⇑, Irina Popova d,1

a

Department of International Trade, Feng Chia University, No. 100 Wenhwa Rd., Seatwen, Taichung 40724, Taiwan

Department of Accounting and Information Technology, Advanced Institute of Manufacturing with High-tech Innovations, National Chung Cheng University, No. 168 University Rd.,

Minhsiung Township, Chiayi County 62102, Taiwan

c

Department of DSC & MIS, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056, United States

d

Feng Chia University, No. 100 Wenhwa Rd., Seatwen, Taichung 40724, Taiwan

b

a r t i c l e

i n f o

Article history:

Available online 24 January 2012

Keywords:

Trust

Privacy policy

Privacy concern

Personal information

Culture

a b s t r a c t

This study aims to investigate trust and privacy concerns related to the willingness to provide personal

information online under the influence of cross-cultural effects. This study investigated the relationships

among the content of online privacy statements, consumer trust, privacy concerns, and the moderating

effect of different cultural backgrounds of the respondents. In specific, this study developed a proposed

model based on Privacy–Trust–Behavioral Intention model. Further, a total of 500 participants participated in the survey, including 250 from Russia and 250 from Taiwan. The findings indicate a significant

relationship between the content of privacy policies and privacy concern/trust; willingness to provide

personal information and privacy concern/trust; privacy concern and trust. The cross-cultural effect on

the relationships between the content of privacy policies and privacy concern/trust was also found

significant.

Ó 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Nowadays, the Internet has become an integral part of our lives.

It has penetrated all sectors of our daily activities: business, communication, shopping, and personal life. There are various types

of online activities offered currently such as Internet shopping,

Web service, e-mail, forum, blog, online game, online banking, online trading, online learning, etc. According to the latest data from

Internet World Statistics, there are 45.3 million Internet users in

Russia and 15.1 million people using the Internet in Taiwan. In

the whole world, there are more than 1.7 billion Internet users.

Globalization and the omnipresent nature of the Internet make

using online activities easier across nations. These activities demand a new conceptual view of online consumers’ behaviors

which take into consideration cross-cultural effects (Phelps, Souza,

& Nowak, 2001). Cultural differences, starting with Hofstede’s

(2001) work, have become an important construct for international

studies.

As the Internet has no borders or regulated restrictions, privacy

becomes a major concern for all online activities. Specifically, consumer apprehensions include the increase of databases, volume of

collected personal data, the possibility of privacy violations, loss of

⇑ Corresponding author. Tel.: +1 513 529 4827; fax: +1 513 529 9689.

E-mail addresses: kwwu@fcu.edu.tw (K.-W. Wu), actsyh@yahoo.com.tw (S.Y.

Huang), yendc@muohio.edu (D.C. Yen), asttw7@gmail.com (I. Popova).

1

Tel.: +886 4 24517250x4265; fax: +886 4 24510409.

2

Tel.: +886 5 2720411x34501; fax: +886 5 2721197.

0747-5632/$ - see front matter Ó 2011 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.chb.2011.12.008

control during the process of collecting, accessing, and how the

information could be utilized (Culnan, 1993; Hiller & Cohen,

2001). Online companies place their privacy policies on their websites to build consumer trust. Online privacy policies are aimed at

reducing the fear that their personal information will be disclosed

(Westin, 1967). Such privacy policies are usually built around the

US Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) five widely accepted principles of fair information practices which are notice, choice, access,

security, and enforcement. Notice is the most fundamental principle, which means consumers should be given notice of an entity’s

information practices before any personal information is collected

and/or obtained from them. Choice means giving consumers the

options as to how to use any personal information collected from

them. Access provides for users’ access to their own data with a

possibility to view the data and also check for data’s accuracy

and completeness. Security means that data must be accurate and

secure. To assure data integrity, collectors must take reasonable

steps and/or actions providing consumers’ access to data, deleting

untimely data, and/or converting it to an anonymous form. Enforcement is one of the core principles of privacy protection which can

only be effective only if there is a mechanism or instrument in

place to enforce them. These are based on national and international reports and guidelines on the use of personal information.

It seems that privacy notices have become an important means

for reducing consumers’ privacy concerns by providing them with

information about how companies use the collected data. It helps

consumers decide whether or not to provide personal information

online or whether or not to even use the website at any level

890

K.-W. Wu et al. / Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2012) 889–897

(Culnan & Milberg, 1998). FTC principles have become widely used

as a base for building privacy notices. Due to the fact that the

Internet is a global phenomenon, online privacy concerns also

become global. Many solutions cannot work or cannot be implemented because consumer thoughts regarding privacy have been

ignored (Hofstede, 2001). Hence, there is a need for research to

investigate why consumers with different cultures react differently

to the content of various privacy policies which may influence their

trust or willingness to provide personal information. Moreover, the

findings based on the data from Taiwan can be a reference for western businesses which are interested in Pan-Chinese regions such

as Hong Kong, Macau, Singapore, and China. As for the findings

based on the data from Russia, these can be a reference for businesses which are interested in east Europe regions such as Latvia

and Yugoslavia.

2. Literature review

2.1. Trust and privacy concern in e-commerce

Online customers often measure the risk of online activity about

information privacy misuse or reveal (Milne & Culnan, 2004). They

must have feelings of trust toward the websites before revealing

information (Schoenbachler & Gordon, 2002). Many research studies propose that concerns over information privacy as well as trust

currently stifle e-commerce. While the regular business sales force

plays a key role in customer interface and market strategy implementation by developing customer trust (Doney & Cannon,

1997), trust assumes a more crucial role in an e-commerce context

where a sales force is not deployed. Businesses anticipate that

many millions of dollars of e-commerce can be conducted if customers’ concerns, including privacy, can be adequately addressed

(Odom, Kumar, & Saunders, 2002). However, completing a transaction without disclosing some personal data is very difficult, if not

impossible, even to a trusted third party (Ackerman, Cranor, &

Reagle, 1999). The research suggests that the willingness to provide personal information on-line is an important issue in e-commerce as well as a trust and privacy concern and can influence

the success of e-businesses.

Privacy has been a sensitive subject long before the invention of

computers. It was defined as the desire of people to choose freely

under what circumstances and to what extent they will expose

themselves, their attitude, and their behavior to others (Westin,

1967). Anonymity, which means to keep the remaining, unidentified information in the public realm, is another crucial concept related to privacy. It means to be able to. Nowadays, the spread of the

Internet eliminates the ability of people using the Web to remain

unidentified. Online users leave a lot of electronic footprints detailing their behavior and preferences that can be easily obtained,

used, or shared with strangers (Zviran, 2008). Because of the rapid

development of new Web technologies, the privacy of Internet

users can be invaded in many different ways. Furthermore, consumers have no control over the secondary use of the personal

information they provide during their Internet activity. In 2004,

more than half of large US firms monitored their employees’ e-mail

(Conley, 2004), which means the firms recorded their employees’

e-mail recipients, e-mail senders, number of words in the e-mail,

time the e-mail was sent, time spent composing e-mail, number

of attachments, and type of e-mail.

The World Wide Web created opportunities for companies to

extend their businesses globally and supported them switching

their activities to the Internet by including online shops, online

auctions, business to business (B2B) and business to consumer

(B2C) platforms, etc. E-commerce provides advantages for Internet

users such as online services, access to product related

information, and easy and fast communication. On the other hand,

huge amounts of personal information about customers are being

collected and utilized by companies through registration forms

and order forms and/or through the use of tracking software or

cookies. This information obtained allows businesses to follow customers’ online activities and gather information about personal

interests and preferences. These data become valuable to companies, as they help identify their customers’ demands, create effective advertising programs, and better sell advertising space on

their websites (Liu, Marchewka, & Ku, 2004b).

In the paper-and-ink world, the sheer physical effort of collecting, archiving, and analyzing such data acts as a deterrent which

helps to protect privacy to a certain extent (Blanchette & Johnson,

2002). However, the growth of technology-based systems not only

changes the quantity and the quality of what can be collected, but

also allows it to be explored and analyzed in increasingly sophisticated ways (O’Connor, 2006). Due to the dramatic increase of various Internet businesses and forms of activities, online users are

normally alerted to privacy concerns. According to a survey by

the American Electronic Privacy Information Center, 90% of respondents feel that privacy is the most pressing concern when shopping

online, rating it more important than prices or return policies (EPIC

Alert 7.16, 2000). Consumer apprehensions also include the increase of databases, volume of collected personal data, and the

possibility of privacy violations, loss of control during the process

of collecting, accessing, and utilizing the information (Culnan,

1993).

Online privacy concern leads to a lack of willingness to provide

personal information online, rejection of e-commerce, or even

unwillingness to use the Internet. Consumer concerns over privacy

not only limit the development of electronic commerce, but may

also affect the validity and completeness of consumer databases,

which may lead to inaccurate targeting, wasted effort, and frustrated customers. To avoid such inaccuracies, Internet companies

should ensure users that their privacy is well protected. The issue

comes down to the level of trust between the consumer and the

company.

Many researchers see this fight for trust as one of the prime barriers to the continued growth of the e-commerce, particularly as

less technically sophisticated consumers who log online are less

capable of distinguishing the valid threats from media hype

(Grabner-Kraeuter, 2002). Building trust becomes a key element

to reduce the privacy concerns of consumers and to improve relationships between consumers and businesses (Milne & Boza,

2000). With the advance of electronic commerce, some consumers

have become concerned about the disclosure, transfer, and sale of

information which businesses have collected from them. These

concerns purportedly are slowing the rate of expansion of electronic commerce (Rubin & Lenard, 2001). Willingness to provide

personal information online is closely related to concerns over privacy. One of the ways to improve consumers’ trust and reduce privacy concern is to build a privacy policy. Such policies provide an

explanation to customers about how websites will use personal

data and consequently inform them about security tools and protection systems of the websites.

2.2. Evolution of privacy policy regulations

Consumers realize that providing personal data can be beneficial. Many know that detailed, accurate information will result in

higher service quality, more relevant messages, and promotions.

Therefore, consumers are willing to provide personal information

but only under certain circumstances (Godin, 1999). A survey

found that 65% of respondents were more willing to provide information online if they had a guarantee that this information would

not be misused (Hinde, 1998). Other studies show that consumers

K.-W. Wu et al. / Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2012) 889–897

would cooperate better if they had the right to force companies to

delete personal information at a later date (Gilbert, 2001).

The privacy issue was noticed at the beginning of data computerization, long before the spread of the Internet. In 1970, the US

Congress adopted the Privacy Act which contained the main principles of Fair Information Practice (FIPPS) including transparency,

use limitation, access and correction, data quality, and security.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development

(OECD) guidelines were introduced in 1980 and played a significant role in the development of guidelines for the Protection of Privacy Flows of Personal Data. The OECD guidelines contained eight

principles including the collection limitation principle, data quality

principle, purpose specification principle, use limitation principle,

security safeguards principle, openness principle, individual participation principle, and accountability principle. These principles

were widely adopted due to their breadth reflecting real-world

flexibility, but the implications of these principles caused some

restrictions and inconvenience for data processors.

In 1990, the commission of the European Community published

the EU Data Protection Directive Principles. It contained eight main

principles. Though the directives focused more on notice and consent, those principles were applied in Europe, Canada, Japan, and

other countries following FIPPS. In mid-1990, the Federal Trade

Commission encouraged commercial websites to publish online

privacy policies. In 1998, the FTC offered its suggestions for a privacy policy. They developed five core principles common to ‘‘fair

information practices’’ of USA, Canada, and Europe including notice/awareness, choice/consent, access/participation, integrity/

security, and enforcement/redress.

In 2004, the APEC Privacy Framework, presented by the Asia–

Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, basically modernized the

OECD Guidelines and included nine principles including Preventing

Harm, Notice, Collection Limitation, Uses of Personal Information,

Choice, Integrity of Personal Information, Security Safeguards, Access and Correction, and Accountability. Nowadays the problem

of which set of FIPPS to apply often occurs. The OECD Guidelines

provide eight, the EU data protection directives eleven, and the

FTC principles only five. Some of the FIPPS provide principle while

some others do not and different FIPPS have different focuses. After

evaluating the existing FIPPS, the FTC principles were chosen as the

most flexible and realistic system. It reflects a materially different

orientation towards data protection than that of earlier FIPPS. The

FTC principles are more concerned with the data collection related

to the consumers and the associated risks that the data collected

would be used for some unanticipated purposes.

891

privacy concerns only if consumers read and use the information

contained in the policies. If the policy is not perceived as comprehensible then it is less likely to be reviewed by users. On the contrary, when consumers perceive that they can comprehend the

Privacy Policy, they are more likely to read the policy and trust

it. This positive relationship was found between online privacy policy and trust (Milne & Culnan, 2004).

At the same, time there is evidence that consumers are often

not consistent about reading privacy policies. Only 54% of respondents indicated they would read the privacy policy upon first visiting a website. Sixty-six percentage of indicated increased

confidence in the website if a privacy policy is present. This may

suggest that most Internet users are reassured by the presence of

a privacy policy, but are less concerned about specific provisions

of the policy (Earp & Baumer, 2001).

H1. Online privacy policy has a negative impact on privacy

concern.

2.4. Privacy policy and trust

Companies try to use different ways to build consumers’ trust in

their websites including an electronic seal for financial transactions providing evidence of the security of website data and online

privacy policy. Liu, Marchewka, Lu, and Yu (2004a) found that a

successful relationship between buyer and seller depends on the

level of the buyer’s trust which is shown in their Privacy–Trust–

Behavioral Intention model. The model explains how privacy influences trust and then, trust influences consumer behavioral intention for online transactions.

Based on the results of the study, strong support exists for the

model. Relationships between privacy dimensions and trust were

found to be significant, but the model does not test the influence

of the presence of FTC categories on privacy concerns. It does not

suggest what kind of content or what format a privacy policy shall

have. Some studies argue that to build trust, privacy policies

should be informative and reassure consumers that disclosing their

personal information is a low-risk proposition (Dinev & Hart,

2006a; Milne & Boza, 2000). It was also noted that a clear and credible Privacy Policy helps marketers build a positive reputation with

consumers (Schoenbachler & Gordon, 2002).

H2. Online privacy policy has positive impact on trust.

2.5. Privacy concern and trust

2.3. Privacy policy and privacy concern

Research shows that people perform a simple risk–benefit calculation when deciding whether or not to disclose their personal

information (Laufer & Wolfe, 1977). If the benefits of disclosure

outweigh the risks, consumers are more likely to disclose. Privacy

notice is an important means for reducing the risk of disclosing

personal information online. It informs consumers about the firm’s

information practices. This information helps users decide whether

or not they want to provide personal data or to choose not to engage in the website at all (Culnan & Milberg, 1998).

Public opinion surveys find that most consumers are concerned

about losing control over the ways in which websites handle their

personal information. This means they indicate high privacy concern. Sixty percentage of users who provided false personal information would be willing to supply their real information if the

website provided notice about how this information would be used

(Harris Interactive, Inc. and Westin, 1997). It suggests that privacy

concerns could be decreased if websites would present comprehensible Privacy Policies. The Privacy Policy is able to reduce

There is a lot of evidence showing significant relationships between trust and privacy concern regardless of providing Personal

Information online. Many researchers propose that concerns for

information privacy are a huge barrier for e-commerce businesses.

Businesses anticipate that more than a trillion dollars of e-commerce could be conducted if customers’ concerns for privacy could

be reduced (Odom et al., 2002). Completing a transaction without

disclosing some personal data is very difficult, even if that disclosure

is made to a trusted third party, so privacy becomes a necessary concern in e-commerce (Ackerman et al., 1999). Without trusted people

retaining personal data that prevents others from seeing or using

that data (Gibb, 1694), increasing perceptions of trust will influence

the privacy concern to permit the customer to determine that the

benefits of disclosure of personal information outweigh the risks

(Luo, 2002). McKnight and Chervany (2002) see trust as a precedent

of information sharing, which reduces privacy concern.

H3. Privacy concern has negative impact on trust.

892

K.-W. Wu et al. / Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2012) 889–897

2.6. Privacy concern and willingness to provide personal information

Internet technologies allow websites to monitor the actions of

their visitors and use this information to personalize content. Consumers also benefit by getting content better matched to their personal needs, wants, and interests. Internet users may find it

beneficial when websites remember basic information about them

and use it to provide a customized service. Although such personalization brings benefits to both parties, if its use comes out, it is a

threat to personal privacy. The power of the Web to obtain, organize, and facilitate the distribution of personal information is

amazing (Valentine, 2000). Sites are able to create click-stream

data, which identifies where the user came from and goes, what

he was looking at and for how long, and even the user’s email address. Such information is collected automatically and often without the user’s knowledge or permission (Kelly, 2000).

A variety of studies have shown that consumers are increasingly

concerned about the lack of privacy protection during online activities. According to a survey of Web users, almost 95% of them

declined to provide personal information to websites at one time

or another when such information was asked (Hoffman, Novak, &

Peralta, 1999b). Another survey showed that 92% of Web users

are worried about online privacy and 61% refused to make purchases online (Ryker, LaFleur, Cox, & McManis, 2002). Consumers’

fears over the misuse of personal data have become the biggest

challenge facing online retailers and online businesses (Kandra &

Brandt, 2003). Such fears lead to providing falsified personal information. Nearly one fifth of consumers maintain a secondary email

address to avoid giving a website their real information (Phelps

et al., 2001). Others simply go elsewhere when required to provide

personal information (EPIC Alert 7.16, 2000).

It is obvious that privacy concerns have a strong influence over

the willingness to provide personal information. Consumers who

are concerned about their online privacy will be unwilling to disclose personal data to websites (Nam, Song, Lee, & Park, 2006;

Wirtz, Lwin, & Williams, 2007) or could be unwilling to make

transactions, as most of such transactions require disclosing credit

card numbers, telephone numbers, e-mail, and postal addresses

(Dinev & Hart, 2006a).

H4. Privacy concerns have a negative impact on willingness to

provide personal information.

2.7. Trust and willingness to provide personal information

The extended privacy calculus model suggested by Dinev and

Hart (2006a, 2006b) shows strong positive relationships between

trust and users’ willingness to provide personal information during

Internet activities. There are many research studies conducted

identifying dimensions of trust in Hyperspace. Some of them are

familiarity, exchange trust, and information privacy trust. According to the theory of Trust and Power, familiarity is a required condition of trust (Luhmann, 1979). The study of Shim, Slyke, Jiang,

and Johnson (2005) showed strong positive relationships between

a high level of familiarity and a high level of trust. In other research, familiarity was found as a predictor of trust (Bhattacherjee,

2002). Exchange trust is defined as consumer confidence that the

website will fulfill its obligations concerning the given promises

(Singh & Sirdeshmukh, 2000). Information privacy trust is violated

by unauthorized tracking and unauthorized information dissemination and refers to a website’s privacy protection responsibilities

(Hoffman, Novak, & Peralta, 1999a). In this way, trust may be

developed through the effective communication of privacy safeguards, market signals that effectively convey high reputation

and credibility, and previous favorable consumer experiences of

perceived value. The development of trust between direct marketers and consumers reduces consumers’ perceived risk, which then

improves consumers’ willingness to share their personal information with marketers.

H5. Trust has positive impact on willingness to provide personal

information.

2.8. Culture difference

Zhang, Sakaguchi, and Kennedy (2007) analyzed the online privacy statements of leading international companies in the USA,

China, Japan, UK, and Australia. The research was based on two factors: degree of application of FTC privacy principles to the online

privacy statement in different countries and the degree of dependence of such application on IDV index (Hofstede’s theory) for

those countries. The study found that individualistic and collectivist countries differ in terms of Privacy Policy focuses. Individualistic countries focus more on the aspect of Notice with privacy

policies, while collectivist countries focus more on the aspect of

choice. As a result, it assumed that for the Internet as a global

hyperspace, a consumer’s cultural background would moderate

his or her attitude toward online privacy concerns and trust.

Pavlou and Chai (2002) in their imperial study propose that cultural differences influence the e-commerce model and moderate

its key relationships. They found that the role of cultural differences was worth attention which emphasized the role of cultural

aspects in multi-national e-commerce research. To investigate

such a moderating effect of cultural differences in Russia and Taiwan, this research chose power distance. Power distance actually

reflects the way a culture handles inequality (Hofstede, 2001).

For power distance, Russia has a much higher score (90) than Taiwan (58).

The research model was developed based on the Privacy–

Trust–Behavioral Intention Model (Liu et al., 2004a) and the

cross-cultural analysis of privacy notices of Global 2000 (Zhang

et al., 2007). All four culture dimensions (masculinity/femininity,

individualism/collectivism, power distance, and uncertainty avoidance) indirectly affect trust formation through the subjective norm.

In addition, power distance directly affects trust formation

(McKnight, Kacmar, & Choudhury, 2004). In high power distance

cultures, less powerful members of the society accept power to

be distributed unequally (Hofstede, 1980). This often means that

people are more likely to tolerate giving up their privacy to authorities than in low power distance cultures.

H6. Power distance moderates the relationship between online

privacy policy and privacy concerns.

H7. Power distance moderates the relationship between online

privacy policy and trust.

3. Research method

The study uses an online questionnaire to identify the relationships between each FTC category in online privacy statements of

websites and trust/privacy concern. Cultural factors such as power

distance are used as moderated variables. This study was designed

to test 7 research hypotheses.

The sample consists of voluntary online respondents in Russia

and Taiwan age 18 years old and over. The survey was conducted

online, which has advantages – low financial cost, implications,

short response time, greater control over samples, and the ability

to directly load data using analysis software (Hofstede, 2001).

K.-W. Wu et al. / Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2012) 889–897

The questionnaire was translated to Chinese and Russian by a certified translation agency and was posted to online forums. There

are 500 respondents who participated in the survey, including

250 from Russia and 250 from Taiwan.

The variables are trust, privacy concern, willingness to provide

information, and the five FTC principles: notice, choice, access,

security, enforcement. Power Distance is used as a moderating variable. The questionnaire was designed based on the measurement

from Culnan, Carlin, and Logan (2006) and Liu et al. (2004b), and

the online privacy survey was developed based on FTC principles.

The research uses 5-Point Likert-type scales with anchors ranging

from (1) strongly disagree to (5) strongly agree, and their measurement items are shown in Table 1. Moderating variable Power Distance (PDI) is measured according to the study of Hofstede (1980).

Russia’s PDI score is 90; Taiwan PDI score is 58. The questionnaire

was developed in English and then translated into Chinese and

Russian.

4. Data analysis and results

4.1. Description of data

In this research questionnaires were collected online and distributed in paper form to randomly chosen respondents of different ages at different times of day. There were a total of 500 valid

responses. The distribution of demographics was as follows:

There were 29.6% male respondents in Taiwan compared to 64%

in Russia and 70.4% female respondents in Taiwan compared to

36% in Russia participating in the survey. In Russia, 34.4% of them

were 21–25 years old, 30.4% were between 18 and 20 years old,

15% between the ages of 26 and 30, 14.4% between the ages of

31 and 35, 13.2% between the ages 31 and 40, 7.2%. In Taiwan of

participants who were 21–25 years old, 44.8% of the age between

26 and 30, 15.6% of the age 31 and 35, 9.6% of the age 31 and 40,

7.6% 18 and 20 and 41 and 50, 5.6%.

A 72.4% of the participants in Russia and 83.6% in Taiwan use

the Internet every day. In Russia, 52.8% take a brief look at the Pri-

893

vacy Policy while visiting a website and 22% read the Privacy Policy

carefully. In Taiwan, 66.8% take a brief look at the Privacy Policy

while visiting the website and 14.4% read the Privacy Policy carefully. In Russia, 74% chose to access an Interactive website, such

as an e-mail service, compared with 40.8% in Taiwan. In Russia,

26% chose to access a commercial website, such as online shops,

compared with 59.2% in Taiwan.

4.2. Test of reliability

There are two basic goals in this questionnaire design: to obtain

information relevant to the purposes of the survey and to collect

this information with maximum reliability and validity (Warwick

& Linninger, 1975). The reliability of a research instrument concerns the extent to which the instrument yields the same results

in repeated trials. The tendency toward consistency found in repeated measurements is referred to as reliability (Carmines &

Zeller, 1979).

Cronbach’s a (alpha) is commonly used as a measure of the

internal consistency of reliability. The coefficient normally ranges

between 0 and 1. The closer it is to 1.0 the greater the internal consistency of the items in the scale. Nunnaly (1978) has indicated 0.7

to be an acceptable reliability coefficient but lower thresholds are

sometimes used in the literature. The Cronbach’s a for each constructs is presented in Table 2.

4.3. Test of validity

Validity can be defined as the degree to which a test measures

what it is supposed to measure. There are basic approaches to the

validity of tests and measures including content validity and construct validity (Manson & Bramble, 1989). This study employs factorial validity as a form of construct validity that is established

through factor analysis. Factor analysis is a statistical approach

involving finding a way of condensing the information containing

a number of original variables into a smaller set of dimensions (factors) with a minimum loss of information (Hair, Black, Babin, &

Anderson, 2010). Principle Component Analysis is used to extract

Table 1

Measurement of variables.

Constructs

Dimensions

Items

Privacy policy

Notice

– The website discloses what personal information is going to be collected

– The website explains why personal information is going to be collected

– The website explains how the collected personal information will be used

Choice

– The website informs whether personal information will be disclosed to a third party and explains under what conditions

– The website gives clear choice (asking permission) before disclosing personal information to third party

Access

– The website allows you to review collected personal information

– The website allows you to correct inaccuracies in collected personal information

– The website allows you to delete personal information from the website record

Security

– The website explains that the domain takes some steps to provide security for personal information has been collected

– The website informs that any personal information will not be disclosed to third party

– The website has the advanced technology to protect your personal information

Enforcement

– The website discloses that there is a law sanctioning those who violate the privacy statement

– The website discloses that the website will take action according to the law against those who violate the privacy

statement

Privacy concern

– The website is obligated to protect privacy

– The website should NOT reveal personal information to a third party

– The website should reveal privacy policy

Trust

– Even if not monitored, I would trust the website to do the job right

– I trust the website that protects personal information

– I believe that the website is trustworthy

Willingness to provide

info.

– You are willing to provide personal information to the website

– You are forced to provide personal information to the websites

894

K.-W. Wu et al. / Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2012) 889–897

Table 2

Reliability of measurement.

Constructs

Dimensions

Cronbach’s a

Notice

Choice

Access

Security

Enforcement

.727

.756

.771

.816

.898

Privacy policy

.857

Privacy concern

Trust

Willingness to provide personal information

.816

.704

.823

Overall

.832

factors and identify the constructs more clearly. The factor loadings

in the confirmatory factor analysis are ranged from 0.70 to 0.88 for

notice, from 0.90 to 0.91 for choice, from 0.80 to 0.88 for access,

from 0.85 to 0.86 for security, from 0.94 to 0.95 for enforcement,

from 0.77 to 0.83 for trust, from 0.58 to 0.85 for privacy concern,

and from 0.71 to 0.72 for willingness to provide information. Since

each factor loading on each construct was more than 0.50, the convergent validity for each scale was established (Hair et al., 2010).

4.4. Hypotheses testing

The primary aim of structural equation modeling (SEM) is to

model covariance’s, which entails proposing a set of relations and

evaluating their consistency with the relations actually observed

in an existing data set (Bollen, 1989). SEM procedures were used

in this study because this approach permits modeling a set of relations among constructs, simultaneous estimation of all hypothesized paths, and estimation of indirect or mediating effects.

Based on Hoyle and Panter’s (1995) recommendations, several fit

indices were used to evaluate fit of the model including comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Incremental Fit Index (IFI) Bollen, 1989, and

the Root Mean Square Error of approximation (RMSEA) Browne &

Cudeck, 1989.

Fit indices evaluate model fit for the data being examined. They

help determine which proposed model best fit the data by showing

how well the parameter estimates account for the observed covariances. Models demonstrate two main types of fit which are overall

fit (chi-squared test, CFI, GFI, AGFI, NFI, and RMSEA) and local fit of

individual parameters. Additional support regarding local fit is

indicated when significant paths are found to be in the hypothesized direction and the magnitude of the item loadings is greater

than .45 (parameter estimates or standardized regression weights)

(Bentler & Wu, 1993; Joreskog & Sorbom, 1989).

A statistically non-significant chi-squared result is considered

optimal, which indicates no statistical difference between the sample and the model covariance matrices (Smith & McMillan, 2001).

Many researchers have established .90 as an appropriate criterion

for determining adequate model fit for the indices of GFI and AGFI

(Bollen & Long, 1993). MacCallum and Hong (1997) examined the

GFI and the AGFI from the perspective of power analysis, and found

that because of the influence of degrees of freedom and sample

size, it is difficult to determine appropriate values for GFI and AGFI

to indicate model fit or a lack of model fit for any particular model.

NFI is used in absolute sense where 1 equals a perfect model fit and

0 equals a complete lack of fit. An index value of .9 or above has

been conventionally regarded as indicating good fit (Bentler &

Bonett, 1980). However, it was found that NFI may not have good

value if the sample size is small (Bentler & Wu, 1993).

The model proposed in this study intends to test the relationship between the degrees of presence of each FTC category in online privacy statements of websites and trust/privacy concern;

the influence of cultural factor such as power distance on the relationships between the degrees of presence of each FTC category in

online privacy statements of websites and trust/privacy concern;

the relationships between privacy concern and trust. To test

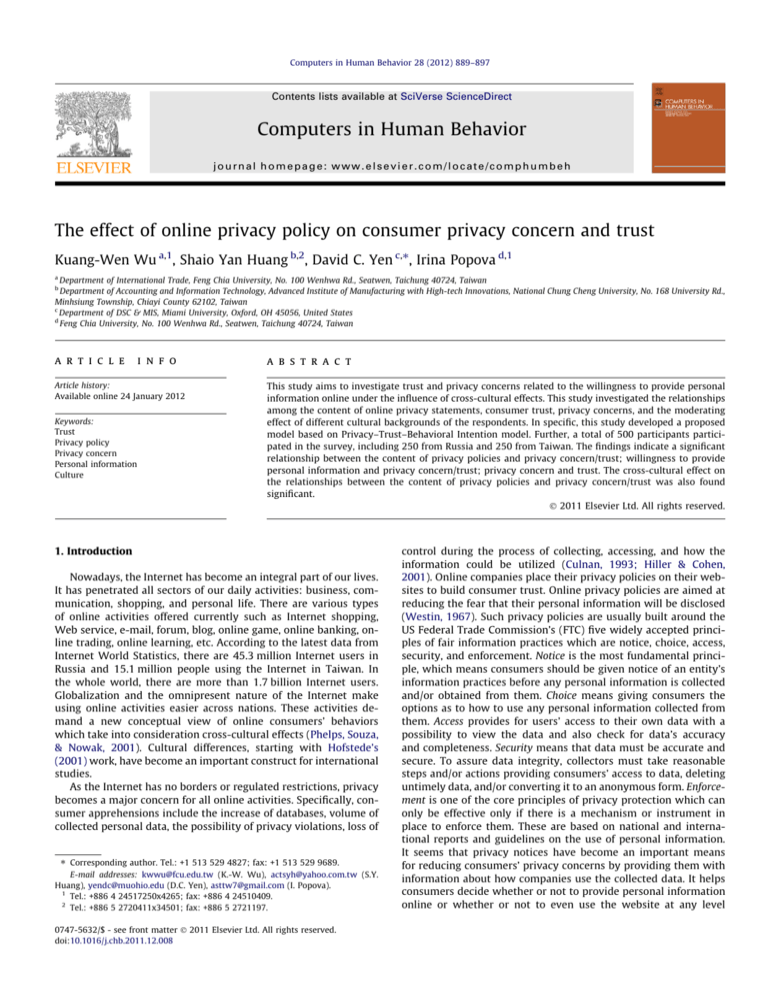

Hypotheses H1–H5, the main effects of the model proposed in

Fig. 1, this study further applied the SEM to generate the appropriate structural model. The goodness of fit indices of the proposed

model were v2 = 776.17, df = 166, p < .001, NFI = .82, CFI = .85,

GFI = .87, and RMSEA = .086. The overall fit measures indicated that

the proposed model had achieved a marginally good fit to the data.

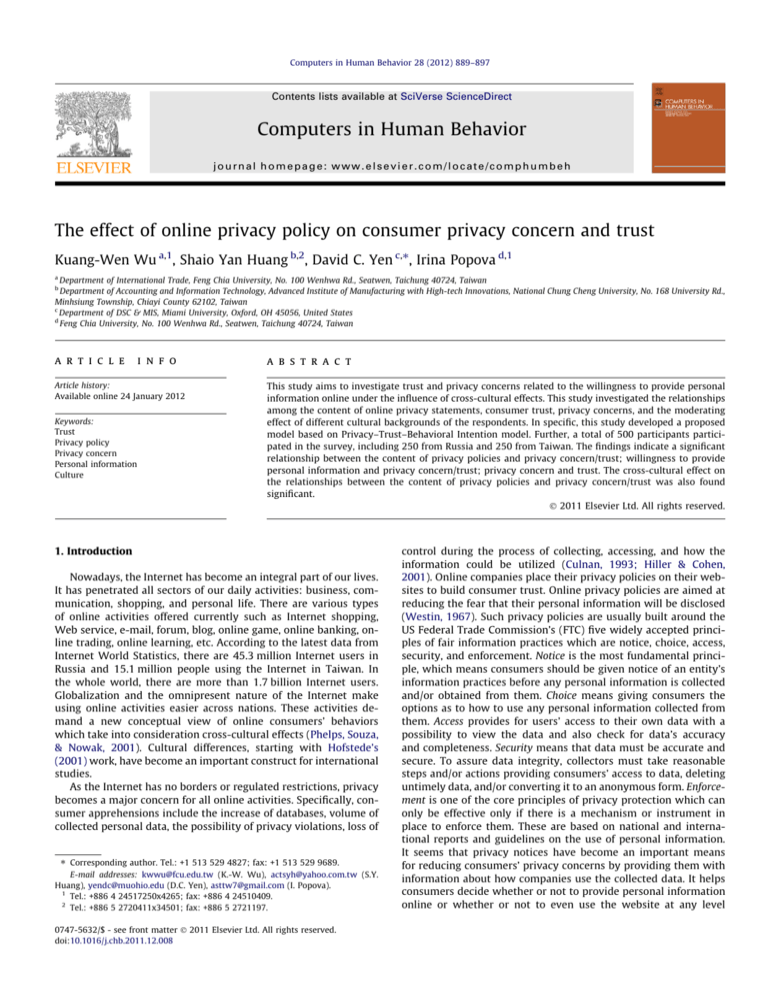

Fig. 2 shows the structure model with the path coefficients and tvalues.

H1 hypothesizes the existence of a negative relationship between a website’s privacy policy and online privacy concerns.

The standardized regression weights for five dimensions (notice,

choice, access, security, and enforcement) were .03, .09, .26,

.75, and .23, respectively. The relationships between the first

two dimensions, notice and choice, were not significant, so H1

was partially supported. H2 proposes the existence of a positive

relationship between a website’s privacy policy and trust. The

standardized regression weights for five dimensions were .24,

.15, .29, .32, and .16, respectively. The relationships between the

two dimensions, choice and enforcement, were not significant, so

H2 was also partially supported. H3 argues the existence of a negative relationship between online privacy concern and trust and it

was supported (standardized regression weight = .43, t-value = 3.90, p < 0.001). H4 states the existence of a negative relationship between online privacy concern and willingness to provide

personal information. Its standardized regression weight was

.17 at a significant level (t-value = 2.66, p < 0.01), H4 was also

supported. H5 addresses the existence of a positive relationship

between trust and willingness to provide personal information.

Its standardized regression weight was .59 at a significant level

(t-value = 7.03, p < 0.001), H5 was supported, too.

4.5. Moderating effect

The Power Distance Index for cultural differences between Russia and Taiwan was chosen as a moderating variable. The PDI for

Russia is 90 indicating a high PDI, while the PDI for Taiwan is 58

indicating a low PDI. The index was chosen as it appears to be

the largest difference in value between two countries compared

to the other cultural indices. Model comparison through AMOS

software was employed to assess the moderating effect of culture

on the relationships between the presence of FTC principles in Privacy Policy and Privacy Concern/Trust.

H6 argues power distance moderates the relationship between

online privacy policy and privacy concern. The result shows that

model comparison is significant between two nations when power

distance moderates the relationship between two presences, Security (p < .05) and Enforcement (p < .05) and privacy concern, which

marginally supports H6. H7 states power distance moderates the

relationship between online privacy policy and trust. The result

shows that model comparison is significant between two nations

when power distance moderates the relationship between two

presences, Access (p < .05) and Security (p < .05)and trust, which

partially supports H7.

5. Conclusion

The study is aimed at investigating how the content of Privacy

Policy relates to Trust and Privacy Concern; how Trust and Privacy

Concern relate to Willingness to Provide Personal Information online under the influence of cross-cultural effects; how the different

cultural backgrounds of the respondents can moderate the results

K.-W. Wu et al. / Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2012) 889–897

895

Power distance

H6

H7

Online privacy

concern

H4

Privacy policy

- Notice

- Choice

- Access

- Security

- Enforcement

H1

Willingness to

provide personal

information

H3

H2

H5

Trust

Fig. 1. Research model.

Privacy policy

Notice

.24

t=2.74**

-.03

t=-.26

-.09

t=-.70

Choice

Online privacy

concern

.15

t=1.33

-.17

t=-2.66**

-.26

t=-3.13**

.29

t=3.80***

Access

-.43

t=-3.90***

-.75

t=-3.56***

.59

t=7.03***

.32

t=3.84***

Security

-.23

t=-2.51**

Willingness to

provide personal

information

Trust

.16

t=1.71

Enforcement

Note. *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Fig. 2. Structural model.

(countries compared are Russia and Taiwan). The model of the

study was developed based on the Privacy–Trust–Behavioral Intention model (Liu et al., 2004a). A total of 500 participants participated in the survey including 250 from Russia and 250 from

Taiwan. The findings indicate significant relationships between

the content of Privacy Policy and Privacy Concern/Trust; Willingness to provide personal information and Privacy Concern/Trust;

Privacy Concern and Trust. The influence of cross-cultural effects

on the relationships between the content of Privacy Policy and Privacy Concern/Trust were also found to be significant.

The Privacy–Trust–Behavioral Intention model (Liu et al.,

2004a) describes the relationship between FTC dimensions, trust,

and intention to participate in online business activities. Mostly

it can be applied to online shopping and activities involving online

transactions and focused on investigating relationships between

Trust and Behavioral Intention. The relationships between Notice,

Choice, Access, and Security were found significant to Trust, but

the model does not test how the presence of FTC Categories would

influence Privacy concern. Then, it does not suggest what kind of

content and format the Privacy Policy shall have. Based on the Privacy–Trust–Behavioral Intention model (Liu et al., 2004a) a more

complex model was developed, which allowed extending the analysis into details such as analyzing the influence of the content of

Privacy Policy (FTC categories) on Privacy Concern and Trust. There

were some variables added in order to apply the model to other

online activities: Web services, emails, forums, blogs, online

games, online trading, and online learning, etc., which require providing different types of personal data. It allowed the investigation

896

K.-W. Wu et al. / Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2012) 889–897

of how Trust and Privacy Concern relate to Willingness to Provide

Personal Information online and what the influence of cross-cultural effects is on these relationships.

The Privacy–Trust–Behavioral Intention model (Liu et al.,

2004a) is based mostly on American perceptions. The present

study extends the perception to other cultures: Asia (Taiwan)

and the West (Russia) to see how online privacy statements content relate to consumer trust and privacy concerns and how the

different cultural backgrounds of the respondents can moderate

the results. The findings indicate significant relationships between

the presence of FTC dimensions in Privacy Policy and Trust, excluding Enforcement and Choice. This confirms the results of the Privacy–Trust–Behavioral Intention model study. Significant

Influence on Privacy Concern with the presence of FTC categories

in Privacy Policy was found, excluding Notice and Choice. The relationships between Privacy Concern and Willingness to Provide Personal Information and Trust and Willingness to Provide Personal

Information are also significant. It suggests that the content of

the Privacy Policies of websites is important for users and influences their intentions to interact with websites if there is a

requirement to provide personal information. Privacy Concern

has significant influence on Trust, which confirms the previous

findings in the literature.

The research also showed that Culture has a significant moderating effect on the attitude of online users to the content of Privacy

Policy. The Power Distance Index was chosen as a moderating variable, which moderates the relationships between the presence of

Security and Enforcement in Privacy Policy and Privacy Concern

and moderates the relationships between the presence of Access

and Security in Privacy Policy and Trust. In other words, compared

to Russian online users, Taiwanese online users increase their trust

in websites when they allow access to their information and when

their personal information is secure.

The study may contribute to further research studies on the

relation between the content of Privacy Policy and Privacy Concern/Trust under cross-cultural effects. It is obvious that culture

differences play an important role in online users’ behaviors and

influence their intentions toward online activities. The results of

the study confirmed earlier findings on the influence of Privacy

Concern over Trust, Privacy Policy content over Trust as well as assessed the influence of Privacy Policy content over Privacy Concern,

Trust and Privacy Concern over Willingness to Provide Personal

Information. The Findings may help further researchers to test

the mentioned relations in more detailed ways, for example, considering different cultural dimensions such as gender and age.

The results of this study would be useful for those companies

who want to create online businesses or activities for Russia or Taiwan (or countries with similar power distance, uncertainty avoidance score), as there is a significant influence of Culture on online

users’ behavior. The companies can increase consumers’ level of

trust and willingness to provide personal data, which in return will

increase their business activity by placing correct information into

their online Privacy Policies.

It would also appear that companies can increase the level of

trust and a customer’s willingness to provide personal data by integrating the notice, access, choice, security, and enforcement

dimensions into the design of their e-commerce websites. The result of the study showed that security is the most important concern of online consumers. It means that if a website wants to

improve the trust of their customers, it needs to focus much more

on providing security and security information while building the

Privacy Policy or the website itself.

The study extends the previous research on relations between

trust, privacy concern, and the content of privacy policy to willingness to provide personal information and assesses cultural influ-

ence on these relationships. The findings should be of interest to

both academics and practitioners.

The research did not analyze the influence of gender over privacy concern/trust and the content of privacy policy. There is evidence in literature that gender may influence privacy concerns and

willingness to provide personal information. While women have a

greater tendency to self-disclosure and have shown more openness

during interviews (Fletcher & Spencer, 1984), there is some evidence that they have a stronger preference for privacy (Marshall,

1974). Age may also influence the relationship between the content of privacy policy and privacy concern/trust. Younger users

may be less concerned about privacy than older users. Some online

research studies find that online privacy worries increase with age.

The type of information collected may influence the willingness

to provide personal data. This research does not specify what kind

of information is being collected and how it is relevant to the purpose of collecting data. Also, further research could study the influence of Power Distance on privacy concern, trust, and willingness

to provide personal information. The research model can be applied to analyze the influence of other cultural dimensions over

the assessed relationships.

Reference

Ackerman, M., Cranor, F., Reagle, J. (1999). Privacy in e-commerce: examining user

scenarios and privacy preferences. In Proceedings of the first ACM conference on

Electronic commerce, Denver, Colorado (pp. 1–8).

EPIC Alert 7.16 (2000). Electronic Privacy Information Center. Washington, DC.

Bentler, P. M., & Bonett, D. G. (1980). Significance test and goodness of fit in the

analysis of covariance structures. Psychological Bulletin, 88, 588–606.

Bentler, P., & Wu, E. (1993). EQS/windows user’s guide. Los Angeles: BMDP Statistical

Software.

Bhattacherjee, A. (2002). Individual trust in online firms: scale development and

initial test. Journal of Management Information Systems, 19(3), 211–241.

Blanchette, J., & Johnson, D. G. (2002). Data retention and the panoptic society: The

social benefits of forgetfulness. The Information Society, 18(1), 33–45.

Bollen, K. (1989). Structural equations with latent variables. NY: John Wiley & Sons.

Bollen, K., & Long, J. (1993). Testing structural equation models. Newbury Park, CA:

Sage Publications.

Browne, M., & Cudeck, R. (1989). Single sample cross-validation indices for

covariance structures. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 24(4), 445–455.

Carmines, E., & Zeller, R. (1979). Reliability and validity assessment. Newbury Park,

CA: Sage Publications.

Conley, L. (2004). The privacy arms race. Fast Company.

Culnan, M. (1993). How did they get my name? An exploratory investigation of

consumer attitudes toward secondary information use. MIS Quarterly, 17(3),

341–362.

Culnan, M. J., Milberg, S. J. (1998). The second exchange: Managing customer

information in marketing relationship. Working Paper, McDonough School of

Business, Georgetown University.

Culnan, M. J., Carlin, T. J., Logan, T. A. (2006). Bentley-Watchfire survey of online

privacy practices in higher education. Unpublished Report.

Dinev, T., & Hart, C. (2006a). An extended privacy calculus model for e-commerce.

Information System Transactions Research, 17(1), 61–80.

Dinev, T., & Hart, C. (2006b). Internet privacy concerns and social awareness as

determinants of intention to transact. International Journal of Electronic

Commerce, 10(2), 7–29.

Doney, P., & Cannon, J. (1997). An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller

relationships. Journal of Marketing, 61(2), 35–51.

Earp, J., & Baumer, D. (2001). Innovative web use to learn about consumer behavior

and online privacy. Communications of the ACM, 46(4), 81–83.

Fletcher, C., & Spencer, A. (1984). Sex of candidate and sex of interviewer as

determinants of self-preservation orientation in interviews: An experimental

study. International Review of Applied Psychology, 33, 305–313.

Gibb, J. (1694). Climate for trust formation. In Leland P. Bradford, Jack R. Gibb, &

Kenneth D. Benne (Eds.), T-group theory and laboratory method (pp. 279–301).

New York: John Wiley.

Gilbert, J., 2001. Privacy? Who needs privacy?. Business 2.0.

Godin, S. (1999). Permission marketing: Turning strangers into friends, and friend into

customers. NY: Simon and Schuster Publishing.

Grabner-Kraeuter, S. (2002). The role of consumers’ trust in online shopping. Journal

of Business Ethics, 39(1), 43–50.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis.

Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

Harris Interactive, Inc., Westin, A., 1997. Commerce communication and Privacy

online. Hackensack: Privacy and American Business.

Hiller, J. S., & Cohen, R. (2001). Internet law and policy. Upper Saddle River, NJ:

Prentice-Hall.

K.-W. Wu et al. / Computers in Human Behavior 28 (2012) 889–897

Hinde, S. (1998). Privacy and security – The drivers for growth of E-commerce.

Computers and Security, 17, 475–478.

Hoffman, D., Novak, T., & Peralta, M. (1999a). Information Privacy in the Market

space: Implications for the commercial uses of anonymity on the Web. The

Information Society, 15(2), 129–140.

Hoffman, D., Novak, T., & Peralta, M. (1999b). Building consumer trust online.

Communication ACM, 42(4), 80–85.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Motivation, leadership and organization: Do American theories

apply abroad? Organization Dynamics, 42, 63.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions,

and organizations across nations (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Hoyle, R., & Panter, A. (1995). Writing about structural equation models. In R. H.

Hoyle (Ed.), Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications.

Thousand Oakes, CA: Sage Publications.

Joreskog, K., & Sorbom, D. (1989). LISREL7: A guide to the program and applications

(2nd ed). Chicago: SPSS.

Kandra, A., & Brandt, A. (2003). The Great American privacy makeover. PC World,

145, 160.

Kelly, E. (2000). Ethical aspects of managing customer privacy in electronic

commerce. Human Systems Management, 19(4), 237–244.

Laufer, R., & Wolfe, M. (1977). Privacy as a concept and a social issue: A

multidimensional developmental theory. Journal of Social Issues, 33(3), 22–42.

Liu, C., Marchewka, J., & Ku, C. (2004b). American and Taiwanese perceptions

concerning privacy, trust, and behavioral intentions in electronic commerce.

Journal of Global Information Management, 12(1), 18–40.

Liu, C., Marchewka, J., Lu, J., & Yu, C. (2004a). Beyond Concern: A Privacy–Trust–

Behavioral Intention Model of electronic commerce. Information & Management,

42(1), 127–142.

Luhmann, N. (1979). Trust and power. Avon, UK: Pitman Press. Translated by

Howard Davis, John Raffan and Kathryn Rooney.

Luo, X. (2002). Trust production and privacy concerns on the Internet. A framework

based on relationship marketing and social exchange theory. Industrial

Marketing Management, 31(2), 111–118.

MacCallum, R., & Hong, S. (1997). Power analysis in covariance structure modeling

using GFI and AGFI. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 32, 193–210.

Manson, E., & Bramble, W. (1989). Understanding and conducting research. USA:

McGraw-Hill.

Marshall, N. (1974). Dimensions of privacy preferences. Multivariate Behavioral

Research, 9(3), 255–272.

McKnight, D., & Chervany, N. (2002). What trust means in e-commerce customer

relationships: An interdisciplinary conceptual typology. International Journal of

Electronic Commerce, 6(2), 35–59.

McKnight, D., Kacmar, C., & Choudhury, V. (2004). Dispositional trust and distrust

distinctions in predicting high- and low-risk Internet expert advice site

perceptions. E-Service Journal, 3(2), 35–55.

Milne, G., & Boza, M. (2000). Trust and concern in consumers’ perceptions of

marketing information management practices. Journal of Direct Marketing,

13(1), 5–24.

897

Milne, G., & Culnan, M. (2004). Strategies for reducing online privacy risks: Why

consumers read (or Don’t Read) online privacy notices. Journal of Interactive

marketing, 18(3), 15–29.

Nam, C., Song, C., Lee, E., & Park, C. (2006). Consumers’ privacy concerns and

willingness to provide marketing-related personal information online. Advance

in consumer research, 33, 212–217.

Nunnaly, J. (1978). Psychometric theory. New York: McGraw-Hill.

O’Connor, P. (2006). An international comparison of approaches to online privacy

protection: Implications for the hotels sector. Journal of Services Research, 6.

Odom, M., Kumar, A., & Saunders, L. (2002). Web assurance seals: How and why

they influence consumers’ decisions. Journal of Information Systems, 16(2),

231–250.

Pavlou, P., & Chai, L. (2002). What drives electronic commerce across the cultures? A

cross-cultural empirical investigation of the theory of planned behavior. Journal

of electronic commerce research, 3(4), 240–253.

Phelps, J., Souza, G., & Nowak, G. (2001). Antecedents and consequences of

consumer privacy concerns: An empirical investigation. Journal of Interactive

Marketing, 15(4), 2–17.

Rubin, P., & Lenard, T. (2001). Privacy and the commercial use of personal information.

Kluwer Academic Publishing.

Ryker, R., LaFleur, E., Cox, C., & McManis, B. (2002). Online privacy policies: An

assessment of the fortune E-50. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 42(4),

15–20.

Schoenbachler, D., & Gordon, G. (2002). Trust and consumer willingness to provide

information in database-driven relationship marketing. Journal of interactive

marketing, 16(3), 2–16.

Shim, J., Slyke, C., Jiang, J., Johnson, R. (2005). Does trust reduce concern for

information privacy in e-commerce?’’ Annual Conference on Southern Association

for Informational System.

Singh, J., & Sirdeshmukh, D. (2000). Agency and trust mechanisms in consumer

satisfaction and loyalty judgments. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science,

28(1), 150–167.

Smith, T., & McMillan, B. (2001). A primer of model fit indices in structural equation

modeling. New Orleans: South Educational Research Association.

Valentine, D. (2000). Privacy on the Internet: The evolving legal landscape. Santa

Clara Computer and High Tech Law Journal, 16, 407–408.

Warwick, D., & Linninger, C. (1975). The sample survey: Theory and practice. New

York: McGraw Hill.

Westin, A. (1967). The right to privacy. New York: Athenaeum.

Wirtz, J., Lwin, M. O., & Williams, J. D. (2007). Causes and consequences of consumer

online privacy concern. International Journal of Service Industry Management,

18(4), 326–348.

Zhang, X., Sakaguchi, T., & Kennedy, M. (2007). A cross-cultural analysis of privacy

notices of the global 2000. Journal of Information Privacy & Security, 3(2), 18–36.

Zviran, M. (2008). User’s perspectives on privacy in web-based applications. Journal

of Computer Information Systems, 48(4), 97–105.