UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN

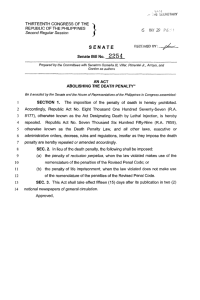

advertisement