Dissertation/Thesis

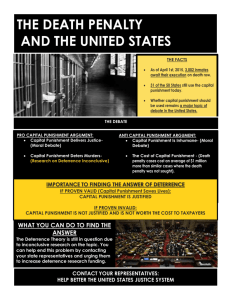

advertisement