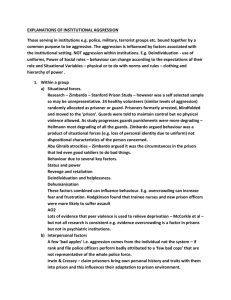

From Childhood Aggression to Delinquency: Causal Pathways

advertisement