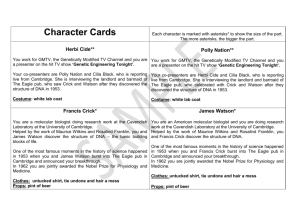

Francis Crick - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

advertisement