Review of Alternatives to 'beeper'

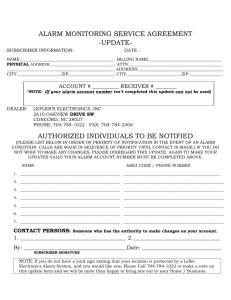

advertisement