The Looming Debate Over Disclosure Effectiveness

advertisement

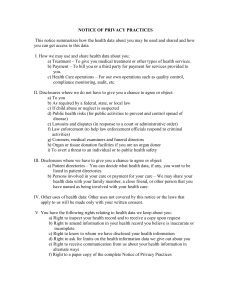

THE ANALYST'S ACCOUNTING OBSERVER Jack T. Ciesielski, CPA,CFA Volume 4, No. 9 August 23 , 1995 The Looming Debate Over Disclosure Effectiveness Corporate managements have long groused that financial statement disclosures have become too detailed and tedious. Those managements may find that their day is at hand, for there are several differing proposals calling for the re-examination or elimination of financial statement disclosures and changes in the format of financial statements, as well. Investment professionals who rely on financial statements for their livelihood need to understand the various outstanding proposals and how they could affect financial reporting. Ignorance of the subject might lead to surprising changes in financial statements later. I. The Current Status The current U.S. financial reporting and disclosure system is the culmination of more than sixty years of statutory guidance, beginning with the Securities Act of 1933. Combined with the private sector standard setting activities of the accounting profession - most notably, the efforts of the Financial Accounting Standards Board and its predecessor, the Accounting Principles Board the investor information provided by U.S. financial reporting and disclosures has helped create a marketplace that is unparalleled in the world. Even the American legal system has helped contribute to the level of financial disclosures enjoyed by investors in the U.S. markets: in the wake of cases like Continental Vending in 1969, auditors have practiced increased diligence with regard to what constitutes adequate disclosure. (In the Continental Vending case, that company’s footnotes were deemed misleading in court when certain related party information involving loan transactions of the company, an affiliate and an officer was not clearly presented - even though such disclosures Table of Contents Page I. The Current Status - Who’s Complaining?...................................................................................................................................... II. The FASB Initiative - Finding Out If There’s Something Worth Fixing............................................................................................ III. The SEC Initiative - Radical Ideas In Washington........................................................................................................................... IV. Second Thoughts - The Road To Hell, Paved With Good Intentions............................................................................................. Copyright 1995, R.G. Associates, Inc. Reproduction prohibited. See last page. 1 3 6 8 -2- were not required by generally accepted accounting principles. Thus, the auditors were held liable to higher standards than those of their profession. The case startled the auditing profession and was probably responsible for more prophylactic disclosures in financial statements than any other event. Eventually, accounting and auditing standards were developed that dealt with related party transactions.) Foreign issuers, while often enviously eyeing the capital raised in U.S. markets, simultaneously find it undesirable to list their issues here simply because of disclosure levels: they do not want to disclose more than they already do in their home markets. Such a position is akin to having one’s cake and eating it, too: what makes U.S. markets so liquid and accessible is information. Foreign registrants aren’t eager to supply the requisite information, but at the same time want the provided benefits. The existing financial reporting system is probably the most light-handed, yet effective, form of regulation present in America today. It provides analysts and investors with the means to evaluate, to question, and most importantly, to set values - whether or not all of the values set are in agreement. That’s what makes horse races and markets. The existing system also has implications for corporate governance and management’s role in the stewardship of assets. Professor Louis Lowenstein of Columbia University summarizes those implications quite nicely: “Not well recognized ... is that, quite apart from the obvious benefits to investors, our financial reporting system has a direct and very positive impact on corporate management itself. Obviously, shareholder rights would be an empty vessel without the information on which to act. But good disclosure means more than that. They, the executives, routinely manage today what they know we will measure tomorrow. We measure a great deal, we measure it promptly, and we enforce the mandate-tomeasure with remarkable vigor. It is a corporate governance tool of the first order, effective, cheap and self-executing”1. Not everyone subscribes to this happy view that the American disclosure system is fine as is. Recall from Volume 4, No.1, “A Top 10 List: Ways To Improve Business Reporting”, the AICPA Special Committee on Financial Reporting (the “Jenkins Committee”) recommended that “standard setters should search for and eliminate less relevant disclosures”. The committee did not identify any specific “less relevant” disclosures. Examples were not volunteered by the analysts with whom the committee met during their data gathering tasks. Curiously, that recommendation found its way into the report of the Special Committee entitled “Improving Business Reporting - A Customer Focus” even though the “customers” did not seem to support the committee’s findings. Apparently, such a recommendation must be based on a feeling or hunch that some disclosures are less relevant, rather than being based on actual findings supported by facts. Another disenchanted view of the current disclosure system appeared in the editorial page of The Wall Street Journal on August 4, 1994. Ray J. Groves, then chairman of Ernst & Young, presented an editorial entitled “Here’s the Annual Report. Got A Few Hours?”, in which he expounded the view that “... total disclosures keep stacking up - and the annual reports you receive every year keep getting bigger. Right now, users often cannot find or recognize - in a reasonable time - those disclosures that affect their investment decisions.” Frankly, the editorial’s title and the author’s assertion are both puzzling. If an investor - institutional or individual - has a significant investment at 1 From a forthcoming paper to be published by the University of Frankfurt Law School, “Financial Transparency and Corporate Governance: You Manage What You Measure” -3stake, spending a few hours with an annual report ought to be relished, not dreaded. The more significant an investment is to an investor’s wealth, the more information he or she should demand rather than less information. If an individual investor cannot fathom the complexities of a firm’s operations and finances as portrayed by financial statements, might that not mean that such an investor is in over his or her head and perhaps ought to seek professional counsel? After all, if the same investor felt ill and couldn’t find a satisfactory cure, the investor would probably seek a doctor: is it sensible to make the field of medicine more accessible to laymen by mandating that medical texts be written so they are user-friendly to lay persons? Mr. Groves also asserted that “we seem to have forgotten that if the accounting is wrong, no amount of disclosure can make it right. And, if the accounting is right, the amount of disclosures needed can be limited to those that matter.” Ironically, this is a great argument for the FASB’s original treatment of the stock compensation issue - which none of the Big Six firms, including Ernst & Young, supported. Is the issue that financial statement disclosures are too complex and dense - or is the reality simply that financial statements are reporting the results of complex and difficult-to-comprehend corporate activities? II. The FASB Initiative To determine if there is enough of an issue to warrant devoting its resources to overhauling disclosures, the FASB has issued a prospectus entitled “Disclosure Effectiveness”. A FASB prospectus is a means of gathering information about the level of interest in a particular topic; the issuance of a prospectus does not guarantee that such a project will be added to the FASB’s agenda. Nevertheless, the prospectus warrants attention from financial statement users: the Board is trying to determine if there is indeed something in the system that is broken, before proposing how to fix it. First of all, what is disclosure effectiveness? The Board sizes up several possible meanings: cost effectiveness, and information overload. • Cost effectiveness. Preparers of financial statements argue that the benefits to users ought to be compared to the costs of preparing, printing and distributing financial statements. Members of this school of thought believe that a consensus about the utility of specific disclosures - and their corresponding relevance - will develop only when their costs are compared to their utility. These folks also believe that those who benefit the most from increased disclosures do not bear their cost, nor suffer any potential competitive disadvantage from disclosure. However, that view ignores the fact that shareholders ultimately bear the cost of producing the information - and they also benefit from them, particularly when they are involved with corporate governance issues. If the firm is competitively disadvantaged by providing disclosures, the shareholders will ultimately suffer as well. Critics of this point of view note that information technology has made the production of information cheaper in the last 20 years, just as disclosures have increased. Corporate staffs have become smaller and more productive as well. Given those trends, one might question whether or not cost effectiveness is a genuine issue. One certainly cannot tell from current financial statements how much their production has cost; developing those numbers alone would probably be quite a -4challenge, let alone developing an expression of utility to outside users. Those who expound the view of cost effectiveness might do well to ask the question: how much would a company’s earnings per share change if all of the “less relevant” disclosures were eliminated? That might put the whole cost effectiveness argument out of existence. Another observation: if companies were truly concerned about cost effectiveness, why don’t they choose to trim - or eliminate - expensive, glossy photographs of plants, workers and board members in their reports? Why not choose cheaper, less shiny paper for printing? Some of the most obvious ways to improve cost effectiveness in investor communications have nothing to do with eliminating disclosures. •Information overload. Proponents of this view are usually preparers and their auditors, who believe that there are simply too many existing disclosures to be truly useful, and their plentitude obscures the usefulness of some of them. “Information overloaders” believe that there are three different approaches to resolving the situation: eliminating less useful disclosures, reduced-content reporting and the elimination of overlapping disclosures. Eliminate less useful disclosures.This has nothing to do with their cost: rather, their expulsion from the financial information package is solely based on their status as “low yield” information. Perhaps this is intuitively appealing, but the hard part is identifying what constitutes less useful information. There certainly has not been a hue and cry from the professional investment community for the removal of “less useful” disclosures from financial statements. Perhaps this is because beauty is in the eye of the beholder; perhaps it’s because users understand that there are times when the same information can be more useful than at other times. Just one use of existing pension disclosures can provide an illustration of this point. Assume a firm has a sizeable, fully funded pension plan; neither overfunding or underfunding is an issue. In a favorable business cycle, users may tend to gloss over such disclosures (even though they shouldn’t) and consider them less valuable than other disclosures. However, when the firm’s business turns difficult, the utility of those disclosures becomes much greater. Users may watch any changes in pension plan assumptions with a beady eye to see if management is trying to costlessly augment earnings, in order to make up for operating shortfalls. Such disclosures provide not only information about the quality of earnings but also the quality of management’s character; the disclosures’ utility becomes greater than they were when the business ran well. There’s no such thing as a “just-in-time” accounting or disclosure standard, however, and throwing out a disclosure when it appears to have a low utility could not be easily remedied when the disclosure becomes more critical to making an investment decision. Reduced-content financial statements. Some proponents of the information overload view believe that an overload could be resolved by creating financial statements with reduced information for specific audiences. That is, send reduced-content financial statements to individual investors, and make “full-strength” financial statements available to professional users. To some degree, the capability to do this already exists: summary financial statements have been permitted in the United States since 1986. The SEC is also currently contemplating a two-tier financial reporting system, whereby “abbreviated” financial statements - ones with only certain footnotes - would be incorporated into the annual report. The remaining footnotes would be included in Form 10-K. (See the next section for more discussion.) The thinking is that firms would be tailoring the information -5to the audience. One point to note about this point of view: it’s difficult to reconcile to the cost effectiveness point of view. Two sets of financial statements means auditor and attorney involvement for both sets, and additional design costs, plus the cost of maintaining records of which interested parties get which kind of statements. Logistically, more preparer effort would be necessary than under a “one size fits all” regime - requiring more costs, instead of trimming them. Overlapping disclosures. Finally, some of those who are of the information overload persuasion believe that relief could be found if a financial report didn’t repeat the same information throughout its course. The best example might be when information in a footnote is also found in a Management’s Discussion & Analysis. (This happened quite frequently when SFAS No. 106 was being implemented for the first time by firms.) It’s certainly true that this situation indicates poor financial journalism, but it’s far from making financial statements unusable. While this might be a waste of newsprint and paper, it shouldn’t be confusing to most readers. It might be annoying at worst, particularly when the information in one area is more thorough or clearer than in another. In its prospectus, the Board notes that some observers believe that the accounting profession could contribute to disclosure effectiveness in two ways. One proposed remedy would be increased recognition of transactions in financial statements in lieu of disclosure: for instance, requiring the capitalization of all leases with a life greater than one year instead of allowing operating and capital treatment. Preparers might favor such an approach when it has a beneficial effect on financial statements (like recognizing deferred tax assets) but resist financial statement recognition when it is less flattering (such as in recognizing stock compensation cost). The second proposed way the accounting profession could improve disclosure effectiveness would be to sharpen the consideration of materiality, making less material disclosures unnecessary. The trouble with this idea is that materiality is a concept that relates well to income statement and balance sheet amounts, but not disclosures. For example, consideration of materiality might address the question of whether or not a charge is significant related to net income or stockholders’ equity. How does such a concept relate to the disclosures that describe the nature of say, a deferred tax asset? A deferred tax asset on the balance sheet begs the question of how long such an asset will be retained by a firm; its expiration provides users with information about cash flows and earnings, which is useful for investors to know. The balance sheet amount alone can’t convey such information; neither can a miniature footnote. ******** The Board merely raises these issues as a trial balloon to see what kind of reaction arises from the user, preparer and auditor communities. The latter two groups will almost certainly respond with ways that financial statement disclosures could be overhauled; users, at least in large quantities, are less likely to do so. Even if they are satisfied with current disclosure effectiveness - and many of them are - concerned users should at least respond in some fashion to the Board. The deadline for comments is November 30, 1995. III. The SEC Initiative -6The SEC has released a proposed rule, “Use of Abbreviated Financial Statements in Documents Delivered to Investors Pursuant to the Securities Act of 1933 and Securities Exchange Act of 1934". The Commission has become quite interested in the disclosure effectiveness issue, and its concern seems to be focused on the use of financial statements by individual rather than institutional investors. Its proposed solution is to permit companies to send abbreviated financial statements to shareholders, while still requiring complete financial statements - and footnotes - to be filed with Form 10-K, which would be available to interested parties upon request. What constitutes “abbreviated financial statements”? The boxes below and on the facing page show what would go into abbreviated financial statements - and what would be left out. The inform- What Would Go Into Abbreviated Financial Statements... Balance sheets, statements of income and cash flows, and changes in stockholders’ equity would be the same as currently reported. Required footnote disclosures: 1. Basis of presentation. 2. Accounting policies. 3. Changes in accounting principle. 4. Restatements and reclassifications (Error corrections and changes in reporting entity as well). 5. Changes in accounting estimate. 6. Business combinations. 7. Discontinued operations. 8. Circumstances identified in explanatory language added to the auditor’s report. 9. Loss contingencies. 10. Events of default under credit agreements. 11. Related party transactions. 12. Bankruptcies and quasi-reorganizations. 13. Subsquent events. Source: Securities & Exchange Commission Release Nos. 33-7183; 34-35893; IC-21166 ation provided by the abbreviated financial statements would not be likely to satisfy a professional investor. Though abbreviated financial statements are a commendable effort to increase the involvement of shareholders by increasing their readability, there are a few troubling issues raised by them: 1. It’s difficult to see how the preparation of two sets of statements will make cost savings for preparers. 2. If it isn’t a dividend check, many individual shareholders will always pitch into the trash can anything that a company sends them - no matter how readable it may be. Efforts to make such statements more user-friendly may be largely wasted on a portion of the individual investor population. 3. Creating abbreviated financial statements effectively creates two “brands” of financial -7statements: “regular” and “deluxe”. At no cost to the shareholder, the “deluxe” version must be provided. Those individuals who become aware of the dichotomy may automatically always prefer the “deluxe” version, whether they need it or not - simply because it’s free. That will increase costs. 4. Making more information available to one group of shareholders than another is not fair, nor should such an informational schism contribute to improved markets. Firms always carry on discussions with analysts with the overriding specter of providing selective disclosure to one analyst or group of analysts, and try assiduously to avoid falling into such a trap. Contrary to current corporate mores, providing abbreviated financial statements to one group of shareholders and fullfledged financial statements to another group is the application of selective disclosure on a grand scale. And A Sample Of Disclosures To Be Left Out... 1. Restrictions on cash; information about compensating balance arrangements. 2. Inventory information: classes, LIFO information, long-term contract terms & conditions, billed & unbilled amounts. 3. Investment securities: types, maturities, realized/unrealized gains or losses, sales & transfers. 4. Loan impairment information. 5. Depreciable assets: classes, depreciation expense, depreciable lives. 6. Intangible assets: classes, amounts and reasons for significant changes; writeoffs; amortization periods. 7. Equity method investments: nature, % of ownership, market value, investee’s summarized financial information. 8. Amount of assets subject to lien. 9. Lease information: Operating leases - expense, commitments, future minimum lease payments, contingent rentals, terms and effects of sale-leasebacks. Capital leases - related assets, interest portion of obligation, future minimum lease payments. 10. On & off-balance sheet financial instruments: terms & characteristics of financial instruments, notional amounts, concentrations of credit risk, fair value disclosures. Hedging activities: nature, offsetting amounts. Derivatives: nature, terms objectives, characteristics. 11. Pension post-employment & post-retirement plan information: plan description, expense details, assets, obligations, assumptions (discount rate, compensation increase rate, earnings rate, health care cost trend rate). 12. Income taxes: components of tax expense, deferred tax assets/liabilities, valuation allowance, reconciliation of effective income tax rate, carryforward information. 13. Redeemable preferred stock: preference details, redemption terms and amounts. 14. Stockholders’ equity: preference details, redemption terms, conversion features, voting rights, dividend restrictions. 15. Stock options & warrants: granted, exercised, terminated & exercisable. Changes in terms or exercise prices. 16. Employee stock ownership plans: plan details, compensation expense, shares allocated & committed to be released. 17. Commitments. 18. Gain contingencies. 19. Nonmonetary transactions. 20. Transfers of receivables with recourse. 21. Cash flows: cash interest & taxes paid, noncash transactions, sales, purchases & maturities of investment securities. 22. Research & development costs. 23. Restructuring charges: nature & basis, description of major actions, amounts expensed by category, employee info. 24. Segment, geographic & currency translation information. -8Disclosures to be omitted that are not yet presented (pending implementation of accounting standards): 25. Accounting for impaired long-lived assets: description of assets and circumstances leading to impairment; amount of loss; where loss is located in income statement; segment affected, if applicable. 26. Accounting for stock options: any disclosures required by pending FASB statement. 5. By excluding the MD&A, some interesting disclosures might never find their way into the abbreviated financial statements. Suppose a firm has an extremely lucrative contract that constitutes a significant part of their earnings, and it expires a week before year end. The following year’s earnings will be adversely affected by the loss of the contract. It wouldn’t need to be disclosed, because its expiration is not a subsequent event. Yet there is nothing in the required abbreviated financial statement package that would address such a forward-looking event. 6. Of the most concern to analysts: by sanctioning certain disclosures as necessary for effective shareholder communication, there is an implied statement that all other disclosures are unnecessary for effective communication. Suppose abbreviated financial statements became widely prevalent. The audience to which they are addressed does not usually complain about lack of disclosures, so their silence might be construed as acceptance. If abbreviated financial statements are then hailed as a success, the next logical step in improving disclosure effectiveness might be to remove many disclosures from Form 10-K. Analysts may be complacent about abbreviated financial statements because the desirable information will still be available in Form 10-K. However, analysts ought to pay attention because abbreviated financial statements could eventually trigger erosion in the information content of the beloved 10-K. Other facets of the SEC proposal: • In prescribing the format of abbreviated financial statements, the SEC is also seeking comment from users as to whether or not such statements would be useful in all disclosure documents required to be delivered to investors that contain financial statements - including prospectuses and registration statements. Full financial statements would have to be made available, however. Timeliness of delivery could become an issue for investors. • There is a safe harbor provision that protects abbreviated financial statement preparers from liability if they deliver such statements in accordance with the proposed rules. That is, an investor could not successfully claim that abbreviated financial statements were misleading because they omitted a certain disclosure that was contained in the full financial statements. • An alternative approach to abbreviated financial statements is also suggested in the proposal: summary financial statements. These reports would contain condensed balance sheets, income statements, and cash flow statements - for a minimum of two years. Footnotes would be optional, with reliance on a narrative review to provide the same kind of information in everyday language. This is to be accomplished without providing a full MD&A. • Currently, proxy rules require firms to provide full audited financial statements to shareholders prior to the election of directors. As an alternative to the plan of replacing full financial statements with abbreviated financial statements, the Commission proposes the rescission of those rules, in order to give firms the most flexibility in communicating with their shareholders. The only requirements would be those of a firm’s particular state law and the trading market for its securities. All of these proposals are bold departures from the existing system. Would investors consider them to be improvements? The Commission wants to know; the deadline for comments is October 10, 1995. -9IV. Second Thoughts While standard setters, accounting firms and regulators hurl themselves at the issue of revamping the basic investor information package, one question begs to be addressed: aren’t existing financial statements simply doing what they should be doing - reporting the events that have occurred over a period of time? Put it another way: firms operate in a more complex, different world now than they did thirty years ago, or even twenty years ago - and they engage in more complex, difficult transactions than they did then. If financial statements seem dense, it may be that they are doing their job - which is to reflect the circumstances in which firms operate. In his Wall Street Journal editorial, Mr. Groves cited a nonscientific survey made by Ernst & Young of the 1972, 1982 and 1992 annual reports of 25 large well-known firms. The findings: from 1972 to 1992, the total pages of annual reports increased an average of 83%; the average number of pages of footnotes increased 325%; and the average number of pages of Management’s Discussion and Analysis increased 300%. Those figures are presented as evidence that disclosures have become too unwieldy. -10- A Look At General Electric General Electric is a complex set of businesses - regarded as well-run, and with many moving parts. How different is the GE of today compared to the GE of thirty years ago? 1965 1994 Total assets: Industrial Credit - $4.3 billion $1.1billion $50.8 billion ($11.0 billion, after inflation) $153.6 billion ($33.2 billion, after inflation) Earnings: Industrial Credit - $345 million $10 million $2,641 million ($571 million, after inflation) $2,085 million ($451 million, after inflation) Business segments: Consumer Products Industrial Components & Materials Heavy Capital Goods Aerospace & Defense Products GE Credit Corporation Total pages in annual report: 33 Aircraft Engines Appliances Broadcasting Industrial Products & Systems Materials Power Generation Technical Products & Services GE Capital Services 65 GE’s industrial assets have increased 156% after inflation; its credit-based assets have swelled by 2,918%. Industrial earnings, after inflation, have risen 66%; credit-based earnings grew 4,410%. The number of identifiable business ran from five to eight (nine, if the 1994 “All Other Businesses” is included). Even if the business mix had remained the same, the sheer growth of the firm would suggest increased complexity. In turn, one would expect a more detailed annual report. Even though the 1994 annual report addressed many things that didn’t exist in 1995 -derivatives and postretirement benefit obligations, among many others, the annual report only doubled. Maybe a doubling of the annual report seems excessive, but not when the information obtained is compared to the increased complexity of the entity. Or are they? Might not the tremendous growth of the companies themselves, and the various businesses in which they currently operate, contribute a great deal to the volume of information presented? In 1972, how many of those firms had the international scope of operations they now possess? How many were using derivative financial instruments? How many were involved in leasing transactions as a means of financing? How significant were the promises they had made to their workers for pension, postretirement and postemployment benefits? How many different kinds of businesses did the firms own in 1972 compared to 1992? How liberally were stock options doled out in 1972? How significant was the legal liability of the firms for environmental damages in 1972 compared to 1992? The answers to all of these questions would very likely indicate that a different corporate world (kinder and gentler?) existed in 1972 versus 1992. Disclosure - and accountingstandards have evolved in response to changes in the business world, and that world is what’s reflected in financial statements of the here and now. Complaining that the financial reporting system has become too complex is like shooting the -11messenger when there’s bad news delivered. Legislating away information cannot turn back the hands of time to a simpler world. R.G. Associates, Inc. The Fidelity Building 210 N. Charles Street, Suite 1325 Baltimore, MD 21201 Phone: (410) 783-0672 Fax: (410) 783-0687 Internet: jciesielski@accountingobserver.com Website: www.accountingobserver.com NOTE: R.G. Associates, Inc. is registered as an investment adviser with the State of Maryland. No principals or employees of R.G. Associates, Inc. have performed auditing or review engagement procedures to the financial statements of any of the companies mentioned in the report. Neither R.G. Associates, Inc., nor its principals and employees, are engaged in the practice of public accountancy nor have they acted as independent certified public accountant for any company which is mentioned herein. These reports are based on sources which are believed to be reliable, including publicly available documents filed with the SEC. However, no assurance is provided that the information is complete and accurate nor is assurance provided that any errors discovered later will be corrected. Nothing in this report is to be interpreted as a “buy” or “sell” recommendation. The information herein is provided to users for assistance in making their own investment decisions. R.G. Associates, Inc., and/or its principals and employees thereof may have positions in securities referred to herein and may make purchases or sales thereof while this report is in circulation.