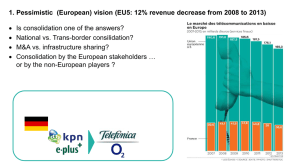

SUBSTANTIVE CONSOLIDATION

advertisement