Juan Ortiz and the Origin of the “Pocahontas” Legend

advertisement

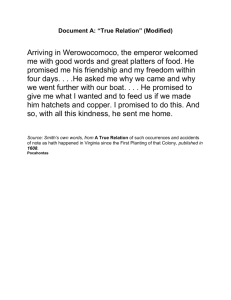

Juan Ortiz and the Origin of the “Pocahontas” Legend Summary A young and adventurous European is captured by natives while exploring the wilderness of the New World. He is brought before a chief, who orders a brutal execution for the wandering explorer. But before the sentence can be carried out, the chief’s own daughter throws herself onto the young European’s bound body and begs for mercy. Sound familiar? It should, because it is the legendary story of John Smith and Pocahontas that has been passed down for over three centuries. But did it ever really happen? And if so, did it really happen to John Smith, or did he “borrow” the story from another source? This lesson seeks to provide some answers to these centuriesold questions. Objectives Students will: 1.) compare and contrast the accounts of John Smith’s capture and subsequent rescue by the Indian princess Pocahontas, and Juan Ortiz’s ordeal in Florida in the 16th century; 2.) use primary and secondary sources to collect evidence pertaining to the authenticity of a legendary event in the historical record; 3.) complete T-chart notes based on evidence received from reading passages. U.S. History Period or Era This lesson can be implemented into any unit dealing with the early explorations and colonization of the Americas. Grade Level Upper elementary or middle school students. Materials Transparency of Picture A-4-1; “Captain John Smith is Saved by Pocahontas, 1608,” “The Juan Ortiz Story,” and “Did Smith Plagiarize Pocahontas Tale? Florida Account Predates Famous Encounter” reading passages, discussion questions, and T-chart notes Lesson Time This lesson can be completed in one class period, or can be divided into two different lessons. Lesson Procedures Procedures 1.) As students walk into the classroom, have the Overhead Transparency (included in the Activities section) projected for all students to see. Instruct the students to answer the three questions below Picture A-4-1 (Option: Have the students respond in their notebook to the following “Preview” question: “Have you ever heard of the legend of Pocahontas? If yes, explain what you know in 2-3 sentences.”) 2.) After allowing students sufficient time to answer the questions about Picture A-4-1, lead a discussion of their answers. Most of your students have probably seen the Walt Disney movie “Pocahontas,” and their answers will probably reflect this. After the discussion, explain to your students that in this lesson, they will find out a little more about the story behind the legend of Pocahontas and John Smith. 3.) Read the following to your students: John Smith was in big trouble. There he sat in the middle of the Virginia wilderness, miles from the struggling new colony of Jamestown, and about to be killed! He was a captured prisoner of Chief Powhatan’s tribes, and several warriors stood over him with clubs ready to crush his head. The story begins when Indians ambush Smith and two English companions. After killing his companions, the Indians take Smith to their chief, Powhatan. After two months in captivity, Powhatan determines to have the Englishman clubbed to death in a ritual ceremony. According to Smith, the plan is thwarted only when the chief’s teenage daughter, Pocahontas, throws herself between him and his attackers causing her father to relent. Smith published his account of the incident in 1624, seven years after the death of Pocahontas. It is the only description of the event we have and, while it is no doubt a legendary story, it was probably romanticized (if not entirely invented) by Smith. Some historians doubt its authenticity, saying that this mock "execution and salvation" ceremony was traditional with the Indians, and if Smith's story is true, Pocahontas' actions were probably one part of a ritual. At any rate, Pocahontas and Smith soon became close friends, and the account permanently etched its name in American folklore. 4.) Pass out the reading passage titled “Captain John Smith Is Saved by Pocahontas, 1608,” giving one copy to each student (you may want to group your students into mixed-ability pairs). Instruct your students to read the passage and answer the discussion questions provided. 5.) After ample time has been given to read and discuss this reading passage, pass out the second passage titled “Did Smith Plagiarize Pocahontas Tale? Florida Account Predates Famous Encounter.” Instruct your students to read this passage as well, and answer the discussion questions provided. 6.) After ample time has been given to read and discuss “Did Smith Plagiarize Pocahontas Tale? Florida Account Predates Famous Encounter,” pass out the reading passage titled “The Juan Ortiz Story.” 7.) Have your students fill out the T-chart reading notes provided with the lesson in pairs. Afterward, you may want to put pairs together for more brainstorming. 8.) After the reading notes have been completed, lead a brief closing discussion on the validity of the legend of Pocahontas. Close the discussion by taking a poll of your students to see which category they all fall under: they believe John Smith’s story to be based in fact; they believe that while parts of John Smith’s story may be true, he more than likely embellished it to make it a better story; or none of John Smith’s story is true because he based the whole thing on the factual account of Juan Ortiz. Overhead Transparency: Picture A-4-1 Activities (from http://saturn.spaceports.com/~boomer/pocahontas/pocahontas-2.jpg) 1. What do you see in this picture? 2. Who are these people? 3. Do you know anything about the story or legend pertaining to these two people? If “yes,” explain it in 2-3 sentences. Captain John Smith Is Saved by Pocahontas, 1608 Captain John Smith was an adventurer. Born in London, England, in 1580, he grew up on his family’s farm. He then worked for a rich merchant until 1596, when, at age 16, he left his home in England to fight against Spain in support of Dutch independence from the Spanish Crown. He would spend the next eight years traveling far and wide as a soldier and a merchant: in 1598 he signed on as a crewmember of a Mediterranean merchant ship; in 1600 he joined Austrian forces fighting the Turks in Hungary. Captured by the Turks, Smith was enslaved and transported to Istanbul. He escaped by murdering his master, returned to Hungary and rejoined the fighting. Released from military duty with a large reward, Smith made his way back to England in 1604. By that time, he had visited Crete, Egypt, Greece, Rome, Venice, Transylvania, Russia, Hungary, and Turkey. Not satisfied with his earlier adventures, Smith soon grew restless. The Virginia Company had recently been granted a charter by King James I to colonize Virginia and Smith eagerly joined the expedition that left England in December 1606. The voyage lasted four months during which the boastful and abrasive Smith so irritated his fellow colonists that they placed him in irons. Arriving in Virginia in April 1607, the expedition leaders opened a locked box containing the names of seven men selected by the Virginia Company to govern the new colony. We can only Picture A-4-2: Captain John Smith imagine their shock when they discovered Smith’s name on the list. The new colonists named their outpost Jamestown, in honor of the King of England. It was the first permanent English settlement in America. The leaders set up the colony as a commune, where everyone shared things equally. Things went well at first, but soon a problem arose: some of the workers did not work as hard as the others. While some men labored to grow, hunt, and find food, others spent their time looking for gold. The people gathering the food began to feel resentful. That winter, as a result of many workers selfishly pursuing their own interests, there was not enough food to go around. Out of the original 93 colonists, 50 died from starvation and disease. Severe weather and Indian attacks also took their toll on the surviving colonists. Captain John Smith finally took over. He told the men, “He that will not work shall not eat!” Under John Smith’s leadership, they built twenty homes, dug a well, began fishing and hunting in regular shifts, expanded the fort, and started a community farm. They gave up the commune idea in favor of private ownership and free enterprise, where each man owned a plot of land to work himself. The colonists liked this idea. They all began to work hard because the land was theirs. Smith’s firm leadership (he was soon elected president of the colony) held the colonists together and saved the colony from extinction. In 1609, John Smith had an accident with a gunpowder bag. It caught fire, exploded, and burned his leg so badly that he had to return to England to recover. He never returned to Virginia. Without John Smith’s leadership, Jamestown suffered its worst winter in 1609-10. All hope seemed lost until another settler, John Rolfe, discovered that tobacco grew wonderfully well in Virginia. The Jamestown colony now had something to sell back in England. A lot of people heard the news and began settling in Jamestown. As for John Smith, he did return to the New World as part of an expedition to explore Maine and Massachusetts in 1614, giving the area the name New England. His independence and abrasiveness disqualified him from any further royal sponsorship and he spent the rest of his life in England writing of his adventures. He died in 1631 at age 51. Saved by an Indian Maiden (During the autumn of 1608, Smith and a small band of Jamestown men explored the area upriver, led by two native guides. Upon reaching a point where their barge could go no further, Smith, the two guides, and two Englishmen proceeded in a canoe. According to Smith’s later account, a band of over 200 natives attacked the barge and killed one of the Jamestown settlers. These same natives then followed Smith’s smaller group and surprised them, taking Smith prisoner but not before he had killed two of his attackers) The following excerpt was taken from Captain Smith’s own account of his rescue. Throughout the following account, Smith refers to himself in the third person: “…finding he was beset with 200 savages, two of them he slew, still defending himself with the aid of a savage his guide, …yet he was shot in his thigh a little, and had many arrows that stuck in his clothes; but no great hurt, till at last they took him prisoner.” “Six or seven weeks those barbarians kept him prisoner, …He demanding for their captain, …they brought him to Powhatan, their emperor. Here more than two hundred … stood wondering at him, as he had been a monster … Before a fire upon a seat like a bedstead, he [Powhatan] sat covered with a great robe, made of raccoon skins, and all the tails hanging by. On either hand did sit a young (girl) of sixteen or eighteen years, and along on each side the house, two rows of men, and behind them as many women, with all their heads and shoulders painted red, many of their heads bedecked with the white down of birds, but every one with something, and a great chain of white beads about their necks. At his [Smith’s] entrance before the king, all the people gave a great shout. The queen … was appointed to bring him water to wash his hands, and another brought him a bunch of feathers, instead of a towel to dry them …, a long consultation was held, but the conclusion was, two great stones were brought before Powhatan: then as many as could laid hands on him, dragged him to them, and thereon laid his head, and being ready with their clubs to beat out his brains, Pocahontas, the king's dearest daughter … got his head in her arms, and laid her own upon his to save his from death: whereat the emperor was contented he should live…” “Two days after, Powhatan having disguised himself in the most fearfulest manner he could, caused Captain Smith to be brought forth to a great house in the woods, and there upon a mat by the fire to be left alone. Not long after, from behind a mat that divided the house was made the most (miserable) noise he ever heard; then Powhatan, more like a devil than a man, with some two hundred more as black as himself,… told him now they were friends, and presently … [Powhatan] would give him the county of Capahowosick, and for ever esteem him as his son Nantaquoud.” Picture A-4-3: A portrait of Pocahontas during her stay in London *It is believed that John Smith and Pocahontas had a father-and-daughter relationship during John Smith’s stay at Jamestown. She was a young girl, maybe thirteen years old at the most. Her original name was Mataoka. She came to visit the colonists often and would playfully turn handsprings and somersaults in the streets of Jamestown. Her nickname, Pocahontas, meant “wanton child who can never be found because she is always off playing somewhere.” Years later, when friendly relations between Pocahontas’ tribe and the English settlers turned into outright hostility, she was captured and held for ransom in Jamestown. Learning that her old friend John Smith was no longer there (in fact, she was told that he had died), Pocahontas met John Rolfe, who was by then a wealthy tobacco farmer. They fell in love, and after she converted to Christianity, they were married. This marriage helped to ensure the return of friendship between the local natives, led by Pocahontas’ father Powhatan, and the English in Jamestown. In the spring of 1616, Pocahontas, her husband, and their young son Thomas sailed to England in order to seek more financial support for the colony. While there, she met King James I, the royal family, and the best of the rest of London society. Even more shocking, she saw her old friend John Smith, who she had been told was dead. In March 1617, Rolfe, his wife Pocahontas (who had been christened Rebecca after her Christian conversion), and their son set sail to return to Virginia. It was soon apparent, however, that Pocahontas would not survive the voyage home. She was deathly ill from pneumonia or possibly tuberculosis. She was taken ashore, and, as she lay dying, she comforted her husband, saying, "all must die. 'Tis enough that the child liveth." She was buried in a churchyard in Gravesend, England. She was 22 years old. “Did Smith Plagiarize Pocahontas Tale? Florida Account Predates Famous Encounter” By Bill Kaczor, Associated Press writer (http://www.s-t.com/daily/07-95/07-11-95/0711APpocahontas.HTML ) When the Indian chief ordered the execution of a European captive, the chief's daughter persuaded him to spare the white man's life. Does that sound like the story of Captain John Smith, the Jamestown colonist, which has been retold in the popular Walt Disney movie "Pocahontas"? Actually, it happened in Florida nearly 80 years before Smith set foot in Virginia: the European was Spaniard Juan Ortiz, and the Indian maiden was known as Ulele. Many historians doubt that young Pocahontas ever saved Smith's life and some contend the Englishman probably made up the story after reading previously published accounts of Ortiz's ordeal. Not until after Pocahontas died in 1617 did the story show up in a revised account of Smith's adventures. Some historians dismiss Smith as a "blowhard" and self-promoter. One biography is titled "The Great Rogue." "It's something nobody can prove one way or the other," said historian William Coker. "But on the other hand the evidence, I think, leans pretty heavily in favor of him borrowing the story." In 1528, Timucuan Indians (of the Uzita village) captured Ortiz and three other Spaniards who were searching for missing explorer Panfilio de Narvaez near Tampa Bay. "The first thing they did was . . . use them for target practice," said Dr. Coker, an emeritus professor of history at the University of West Florida. Three of the Spaniards were killed by arrows but Ortiz survived, he said. Hirrihugua, chief of the Uzita village, had a score to settle with the Spanish because Narvaez had cut off his nose and killed his mother by throwing her to a pack of dogs. The chief saved Ortiz for a special torture called "barbacoa," a word that survives as "barbecue." Ortiz was strung up over a fire to be roasted alive but Ulele pleaded with her father to spare his life. The chief's wife joined in the appeal and he relented. However, the chief again threatened to have Ortiz killed. Before his sentence could be carried out, Ulele helped Ortiz escape to the village of a neighboring chief, Mocoso. Ortiz lived there in relative peace until he encountered Hernando de Soto's expedition 11 years later. Ortiz, covered with tattoos as was the Timucuan custom, joined the Spaniards as an interpreter. He and de Soto both died during the winter of 1541-42 in present-day Arkansas, near the Mississippi River. A de Soto survivor known as the Gentleman of Elvas included the Ortiz rescue in his account of the expedition published in Lisbon, Portugal, in 1557. An English translation was printed about 1605. A Spanish account by Garcilasco de la Vega appeared in 1601. "Lisbon and London were on good terms," Mr. Coker said. "There's no question in my mind that copies of the book in Portuguese, Spanish and English were in London early on and early enough for Smith to have made a thorough study of them." Smith encountered Pocahontas in 1607 and returned to England two years later. Pocahontas married another colonist, John Rolfe, in 1614 and they moved to England in 1616. She died a year later. Smith's tale of rescue, never written about by any other colonists, does have supporters. Some say he may have left out the rescue initially to avoid scaring away potential colonists. Others say his first writings were heavily edited, possibly deleting the Pocahontas story. But Helen Roundtree of Old Dominion University in Norfolk, Va., has another reason for doubting the Pocahontas rescue story. It claims that Pocahontas' father, Powhatan, planned to bash out his brains with stones. The Indians of that time and place would have used a slower, more torturous method of death, she said. The Juan Ortiz Story So, if John Smith actually did make up the entire episode about Pocahontas saving his life, from where did he get the idea? Recently, historians have mentioned the incredible true story of a young Spanish sailor named Juan Ortiz as the possible origin of the Pocahontas legend. But in order to understand the story of Juan Ortiz, one must first become familiar with the exploits of Panfilo de Narvaez, a Spanish conquistador who led a doomed attempt to explore and conquer Florida in the early 16th century. Panfilo de Narvaez, a veteran Spanish soldier in the early years of conquest in the Caribbean, was a favorite of Charles V, the king of Spain. In June 1527, de Narvaez set sail from Spain with 600 men and five ships on a mission to conquer and govern Spanish land claims from the Rio Grande to Florida. After stops in the Caribbean, he sailed with 400 men and eighty horses. On Good Friday, April 15th, 1528, de Narvaez’s ships landed near present-day Clearwater on the Pinellas peninsula, on the west side of Tampa Bay. After raising the flag of Spain and taking possession of all of the surrounding land in the name of his king, de Narvaez and his men encountered members of the nearby Uzita tribe. Following them to their village, de Narvaez’s men discovered some crude gold ornaments. Immediately, the Spaniards began a campaign of torture and enslavement of the peaceful Uzita tribe. In the search for gold and silver, natives were made to serve as guides and burden bearers. When the tribe’s chief proved unwilling or unable to reveal the location of any treasure, he was forced to watch as his mother was torn to shreds before his eyes by fierce war dogs that accompanied the Spaniards. De Narvaez then ordered the nose of the chief to be cut off in order to get him to tell of hidden gold. As a result, the chief made up a story of how a great tribe to the north, the Apalachee, ruled a great kingdom of riches in the Tallahassee Hills. With visions of treasure and glory equal to that of his contemporaries Pizarro and Cortes, de Narvaez and his soldiers began a long march north toward the Panhandle. Because of his brutal treatment of the Uzita people and other natives that were encountered along the way, the de Narvaez expedition would damage Spanish-Indian relations for decades. They left behind a legacy of violence and trickery. Upon reaching the Tallahassee Hills, de Narvaez would find only poor farming villages. Ordered to return to Cuba for provisions and come back to outfit the band of conquerors, de Narvaez's fleet returned to Tampa Bay, but found no sign of the expedition that was still marching through Apalachee territory. After searching for their captain and his men up and down the Gulf Coast of Florida, they ended their search and returned to Cuba. De Narvaez's wife soon hired a group of sailors to find her husband. Upon reaching Charlotte Harbor, the agreed-upon rendezvous point for de Narvaez and his ships a year earlier, the rescuers were heartened by what appeared to be a note placed on a stick on a deserted beach. Thinking that it may have been a note left by de Narvaez or a member of his expedition, several men rowed a boat to shore to investigate further. One of these men was the eighteen-year-old Juan Ortiz. The note was a trap that had been set, of all people, by Hirrihigua, the same chief who had watched his own mother be ripped to shreds by de Narvaez’s dogs…the same chief whose nose had been cut off because he would not reveal the source of his tribe’s gold. Needless to say, Hirrihigua, in his anger, sought revenge on Juan and the other captured Spaniards for his earlier treatment at the hands of de Narvaez. First, he made one of the hostages run around the village square while Indians shot arrows into his body; then, he had the others tied to trees and used for target practice. For Ortiz, though, Hirrihigua had a special torture in mind, since he believed the young Spaniard to be a son of the despised de Navaez. Hirrihigua had Juan tied to a barbacoa (a smoking and drying rack for foods and hides, a word that survives today as “barbeque”) and placed over a fire to be slowly cooked to death. However, Hirrihigua’s wife and two of his daughter’s begged for the young Spanish boy’s life, throwing themselves at the feet of the chief. Begrudgingly, Hirrihigua relented. Suffering greatly from his burns (which scarred him for the rest of his life), he was attended by the village’s medicine man. Although Juan was spared that day, he was made a slave and given the most despised jobs, such as keeping animals away from a temple that doubled as a burial place for the village’s dead. It was understood that if a predator took even one body, Ortiz’s death sentence would be carried out. Meanwhile, Hirrihigua’s hatred toward the young boy continued to grow. Many times he had Juan tortured and threatened to carry out his death sentence, only to be persuaded by his wife and daughters to stop. Picture A-4-4: A reenactment of Ortiz being placed on a barbacoa. (http://www.angelfire.com/fl3/calderonsco/school.html ) The chief’s eldest daughter, Ulele, decided that she and her mother and sisters could no longer protect Juan from her father’s rage, so she helped him escape to the village of a neighboring village ruled by Ulele’s fiancé, Mocoso. Ortiz lived in relative peace for the next ten years under the protection of Chief Mocoso. Hirrihigua, meanwhile, was so enraged by his daughter’s betrayal that he forbade her to ever marry Mocoso. In 1539, another expedition, this one led by Hernando de Soto of Spain, explored the interior forests and swamps of Florida. Some of de Soto’s men encountered a tattooed man; thinking that he might be a hostile native, they prepared to run him through with their weapons. Imagine their surprise when the man made the sign of the Cross and spoke Spanish to them! After eleven years living among the natives in Florida, Juan Ortiz had finally been found by the expedition of Hernando de Soto. Having learned the different native languages after years of captivity, Ortiz served de Soto as a guide and interpreter during de Soto’s travels around Florida and the Southeast. Both Ortiz and de Soto died near the Mississippi River in the winter of 1541-42, but not before Ortiz had told his story to one expedition member known only as the Gentleman of Elvas. The only thing known about this man was that he was a Portugese adventurer who survived the expedition, returned to Portugal, and published an account of the de Soto expedition, including a description of the Ortiz rescue, in 1557…twenty-three years before John Smith was even born! An English version was published in 1605. Two years later, John Smith met Pocahontas, and the rest is…history. Discussion Questions for “Captain John Smith Saved by Pocahontas, 1608” 1. Based on the reading, would you consider Captain Smith’s early life to have been one full of travel and adventure? Explain your answer. 2. Why did Smith’s fellow travelers on the way to Virginia in 1606-07 place him in irons? Do you think that the colonists regretted their decision to do this later? Why or why not? 3. Was John Smith a good leader for the colony of Jamestown? Support your answer with evidence from the passage. 4. According to the writer, why did the commune system not work for the colony of Jamestown? What did Smith do to fix this problem? 5. Read Captain Smith’s own account of his capture, imprisonment, and near-death experience at the hands of Powhatan. How long was he a captive of the natives? How do you think he felt? If he was scared, do you think he showed his fear? 6. What evidence in Smith’s account of Pocahontas shows that Powhatan was a very powerful chief? 7. In 2-3 sentences, give a brief biographical sketch of Pocahontas according to the reading passage. Discussion Questions for “Did Smith Plagiarize Pocahontas Tale?” 8. How many years before John Smith’s tale of Pocahontas became public did the ordeal of Juan Ortiz take place? 9. Based on this passage, do you think that the writer believes Smith’s account of his rescue, or do you think that he believes that Smith made it up? Use evidence from the passage to explain your answer. Discussion Questions for “The Juan Ortiz Story” Why did Juan Ortiz come to Florida? How was he captured? Why did Hirrihigua, chief of the Uzita, want to kill Ortiz? Was revenge a motive? If so, explain how. After Ortiz was rescued by Ulele, how was he treated by Hirrihigua afterwards? When it became clear to Ulele that Hirrihigua was going to finally have Ortiz put to death, what did she do? What did Hirrihigua do in response? 14. Who finally “found” Ortiz? Was this a lucky find for both? Explain your answer. 15. What became of Juan Ortiz? 10. 11. 12. 13. Reading Notes on the Legend of Pocahontas Similarities between the John Smith account and the Juan Ortiz account Evidence that refutes the account of John Smith Assessment 1.) Have your students create a “DVD cover” for the “real” story of Pocahontas, except that this one includes a title and visuals that illustrate important details about the story of Juan Ortiz and Ulele. Have students include “quotes” from critics; colored pictures from the Internet, magazines, or hand-drawn; and some writing that describes some of the action described in the factual account of Juan Ortiz. Have your students use real DVD covers for examples. 2.) True or false. Pocahontas was not a real person. Instead, she was entirely made up by an English explorer named John Smith in the hopes of selling books. 3.) True or false. Though Pocahontas and John Smith were very close, she ended up marrying a wealthy tobacco planter named John Rolfe. 4.) It is believed that John Smith may have gotten the idea for the Pocahontas legend by reading the real account of a Spanish sailor named _____ _______, who was captured by natives in Florida almost eighty years before John Smith met Pocahontas. a. Panfilo de Narvaez b. Juan Ortiz c. Hernando de Soto d. Juan Ponce de Leon 5.) Following are a list of names from the story of Pocahontas. In the spaces to the right, fill in the names of their counterparts from the real-life ordeal of Juan Ortiz: Hero: Indian princess: Indian chief: Coutry of origin: Pocahontas legend John Smith Pocahontas Powhatan England Juan Ortiz story a. ??????????? b. ??????????? c. ??????????? d. ??????????? Here are your choices: a. Juan Ortiz, Juan Ponce de Leon, Hernan Cortes, Francisco Pizarro b. Ulele, Uzita, Mocoso, Hirrihigua c. Uzita, Timucuan, Hirrihigua, Osceola d. France, Spain, Portugal, United States Resources http://www.apva.org/history/pocahont.html -Pocahontas biography http://www.apva.org/history/jsmith.html -John Smith biography http://www.s-t.com/daily/07-95/07-11-95/0711APpocahontas.HTML - “Did Smith Plagiarize Pocahontas Tale? Florida Account Predates Famous Encounter” http://www.angelfire.com/fl3/calderonsco/school.html http://saturn.spaceports.com/~boomer/pocahontas/pocahontas-2.jpg http://www.floridahistory.org/floridians/conquis.htm -“Florida of the Conquistador” http://www.ancientnative.org/juan.htm -“The Story of Juan Ortiz” http://1st-history-of-the.us/inset44a.html -“De Soto’s Background” (for another fascinating true story about a young Spaniard living with natives in the wilderness of Florida, go to http://www.keyshistory.org/Fontenada.html and read the first-hand account of Hernando D’Escalante Fontaneda) Fleming, F.P. “The Story of Juan Ortiz and Uleleh.” The Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 1, no. 2. Gannon, Michael V. “Altar and Hearth: The Coming of Christianity.” The Florida Historical Quarterly, vol. 44, no. 1 & 2. Gannon, Michael, Ed. The New History of Florida. University Press of Florida: Gainesville, FL. 1996. “How John Smith Saved Jamestown!” USA Studies Weekly (a weekly newspaper for young students of United States history), Vol. 5, Issue 2; Series A (Explorers to the Civil War), 2003-2004. Judge, Joseph. “Between Columbus and Jamestown: Exploring Our Forgotten Century.” National Geographic, March 1988; 330-63. Tebeau, Charlton W. A History of Florida. University of Miami Press: Coral Gables, FL. 1971.