Journal of Cleaner Production 6 (1998) 269–275

Exploratory examination of whether marketers include stakeholders

in the green new product development process

Michael Jay Polonsky

a

a,*

, Jacquelyn A. Ottman

b

Department of Management, University of Newcastle, Newcastle, NSW 2308, Australia

b

J. Ottman Consulting, Inc., 1133 Broadway, New York, NY 10010, USA

Abstract

Many firms are attempting to make their products less environmentally harmful. However, marketers and others within the firm

often have limited environmental expertise. When attempting to ‘green’ its products, it is therefore important that the firm include

a broader set of stakeholders in the green new product development (NPD) process, as this ensures that all relevant environmental

issues are considered. This paper examines US and Australian marketers’ perceptions of stakeholders’ involvement in the green

NPD process to determine whether stakeholders with this broader environmental expertise are included. It also examines the specific

strategies US marketers within the study used to involve these groups in the green NPD process. It was found that the strategies

used were basic in nature and some additional strategies are suggested. 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

Keywords: New product development; Stakeholders; Green marketing

1. Introduction

It has been suggested that the 1990s is the decade of

the environment. Going green is not only good for the

environment, but it also provides a competitive advantage for businesses [1,2]. While an increased interest in

the environment has important ramifications for all

aspect of business, it may also require a substantial shift

in corporate culture [3], thus ensuring that environmental

objectives are core issues of consideration.

The literature suggests that marketers traditionally

play an active role in the development of all new products, green and non-green alike [4–6]. While this paper

assumes that marketers are key players in the new product development (NPD) process, it also recognises that

there are other key internal players as well. Given marketers’ zeal to market new innovative products and ideas,

it is therefore not surprising that they have been quick

to jump on the green bandwagon [7], developing and

promoting the environmental ‘benefits’ of their products

[5,6,8]. This has resulted in the development of new pro-

* Corresponding author. Tel.: 61-2-4921-5013; Fax: 61-2-49216911; E-mail: mgmjp@cc.newcastle.edu.au

0959-6526/98/$19.00 1998 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

PII: S 0 9 5 9 - 6 5 2 6 ( 9 7 ) 0 0 0 6 4 - 4

ducts, refinement of existing products or simply ‘promoting’ existing goods differently. However, in the past

many of these ‘new’ green products have failed in the

marketplace. This has occurred because: (1) they do not

substantively improve the product’s environmental performance; (2) the product’s environmental ‘benefit’ is

questionable; or (3) the product does not perform as well

as traditional products.

This is not to suggest that there are no truly environmentally innovative firms. Some firms and their products

have been recognised as less environmentally harmful

by leading environmental groups, as well as by various

industry associations. For example, within the American

Marketing Association’s (AMA) Edison Awards for new

product development, there is a special category for

recognising leading environmentally oriented products

[9,10]. The fact that there are a growing number of

entrants in this award category is one indication that

‘real’ environmental changes are taking place. Marketers

and others involved in the NPD process are integrating

the environment into the corporate culture and are not

simply tacking it on as an afterthought [9].

For ‘real’ environmental improvements to occur, marketers need to consider the environmental impacts of all

activities before the product is designed or modified

270

M.J. Polonsky, J.A. Ottman / Journal of Cleaner Production 6 (1998) 269–275

[5,6]. However, marketers will most likely will be

unfamiliar with all of the environmental intricacies of

their firm’s activities and would therefore need to obtain

input from various stakeholders with environmental

expertise [8]. As this information may not even be available within the firm, marketers may be forced to rely

heavily on a broad set of external stakeholders for

environmental input. Simply focusing on customers and

suppliers will be insufficient, as these groups frequently

do not have all the essential environmental information

needed to ensure that a product’s environmental harm

is reduced.

Some firms already involve a broad set of stakeholders

in their green NPD processes, including environmental

groups [11–13]. For example, in their quest to replace

polystyrene clamshell packaging, McDonalds consulted

with the Environmental Defense Fund. In another situation the Canadian retailer Loblaws asked Pollution

Probe to assist them in developing a range of environmental products [13,14], and it was an environmentalist

who first suggested to Church and Dwight that their Arm

and Hammer Brand could be used as an environmentally

preferable cleaning product.

These external groups usually have a better understanding of the relevant environmental issues and can

thus assist organisations in producing less environmentally harmful products. The involvement of more stakeholders in the formulation of environmental marketing

strategy should enable marketers to consider all of the

relevant environmental issues. However, including

additional stakeholders may result in product development and implementation processes becoming more

complex.

This paper is an exploratory examination of marketing

managers’ perceptions, to identify which stakeholders

they believe should be ‘involved’ in green product development and how they have involved these groups. This

is done through an examination of two separate samples.

The first involves an in-depth examination of US marketing managers whose products have won the Environmental Edison Award during 1993–1996. The second

involves examining Australian marketers’ attitudes

towards stakeholders in the green product development.

It is envisaged that the results will provide information

that can be used by marketing managers to include

environmental marketing stakeholders in green product

development in the future.

2. Background

New product literature identifies that there are many

areas where stakeholders can assist with NPD, with most

of the research examining the generation of new product

ideas. Traditionally, a broad range of stakeholders are

involved in the NPD process, including: buyers, cus-

tomers, R&D departments, company executives (e.g.

marketing, finance, manufacturing), competitors, freelance

investors,

government,

suppliers,

and

universities/scientific community [5,15,16]. Some

research has suggested that different types of industries

(high verses low technology industries) require the

involvement of different stakeholders [16]. The interaction between stakeholders and the firm is growing and

becoming more complex. To ensure that innovative products are developed, it is therefore necessary that firms

form strategic alliances with their stakeholders [17]. In

the green product area there are many ‘real world’

examples of where firms have worked with stakeholders

to develop such environmentally improved products

[11–14].

The degree of stakeholder involvement will vary by

situation and, while some stakeholders are not directly

involved in generation of new ideas, it is important for

them to be involved if the product is to succeed. For

example, financial bodies may be willing to share the

risk of developing a new product in return for a higher

stake in the investment [17]. While these stakeholders

may be essential to the NPD process, it is unclear

whether they play an active role in the generation of

new ideas. Furthermore, it is unclear whether marketers

traditionally consider how the firm could interact with

these ‘other’ stakeholders and thereby ensure the successful development of these new green products.

The involvement of internal stakeholders is also discussed extensively in the new product literature, with

some authors focusing on the use, management and

structure of new product or innovation teams [18,19].

Much of this work focuses on the specific types of structures that enable the firm to bring products to the market

more quickly, cheaply, or efficiently. Firms regularly

involve internal stakeholders who control key resources

or have specific expertise that makes the process more

effective, and there is no reason that the same

approaches could not be applied to deal with external

stakeholders [20].

The green NPD process appears to extensively involve

those external stakeholders [11–14]. One reason for this

is that environmental issues have traditionally not been

a ‘core’ function for most firms and even if they wanted

to be leaders in the environmental area they would not

have the necessary expertise to do so. External assistance

allows firms to keep pace with rapidly changing environmental technology and environmental regulation.

While it is recognised that a broad set of stakeholders

are important to green NPD, the authors have not found

any research that examines how these groups could or

should be incorporated into this process. However, there

is some work that examines specific cases [14,21].

Should organisations simply open lines of communication with stakeholders, actively include them in the

planning process, or form formal strategic alliances to

M.J. Polonsky, J.A. Ottman / Journal of Cleaner Production 6 (1998) 269–275

achieve some common objective? Alternatively, organisations could simply choose to ignore these environmental stakeholders and thus not incorporate them into the

process at all. Polonsky has suggested that there are four

broad types of approaches that can be adopted to include

stakeholders or address their interests [22]. Firms can

adopt a(n):

1. isolationist approach, where the firm attempts to

minimise the impact of a given stakeholder, without directly interacting with the stakeholder;

2. aggressive approach, where the firm attempts to

directly change the stakeholder’s views or ability

to influence organisational outcomes;

3. adapting approach, where the firm modifies its

behaviour according to the stakeholder’s interests; and

4. cooperative approach, where the firm attempts to

work with the stakeholder to achieve a desired set

of outcomes.

Furthermore, Polonsky [21] has suggested that stakeholders can affect marketing behaviour/development in

three ways: directly threaten, directly cooperate, and

indirectly influence others to act. He also noted that at

any one time each stakeholder has varying levels of all

three influencing abilities [22]. Whether stakeholders

exert those abilities is another matter. Organisational

behaviour and strategy are therefore largely dependent

on how stakeholders behave [8,22]. A stakeholder who

has a low cooperating, low threatening and low indirect

influencing ability might only require that the firm monitor the stakeholder for changes in their behaviour.

Whereas if a stakeholder has a high level of these three

influencing abilities, the firm might be more likely to

formally include the stakeholder in the development process, or adopt behaviours consistent with the stakeholder’s concerns, thus getting them or keeping them

on-side.

3. Methodology

Two different samples were examined to determine

whether marketers believe that stakeholders have the

ability to influence green marketing activities and green

NPD processes. One sample was examined in more

depth to determine what specific strategies marketers use

to address stakeholders’ interests in the green NPD process.

The first sample surveyed US marketing managers

who had been involved in the development of products

winning the AMA’s Environmental Edison Award

[9,10]. These managers were asked to evaluate the

potential influence of 13 stakeholders in the development

and marketing of these green products (academics/

scientific community, competitors, employees/unions,

271

end customers, federal government, local community,

media, retailers/trade, shareholders/owners, special interest groups, state and local government, suppliers, top

management). Respondents were asked to rate stakeholders’ three influencing abilities on a seven-point

scale, where 1 is very high ability and 7 is very low

ability. The three questions were loosely based on the

work of Kreiner and Bhambri [23], who asked a similar

question regarding stakeholders’ attributed power [23].

The three questions asked managers to evaluate stakeholders’ direct threatening ability, direct cooperating

ability, and ability to indirectly influence others to act.

Using a seven-point scale, where 1 is very high ability

and 7 is very low ability, US respondents were also

asked to evaluate the importance of each group to the

new product process. Lastly, they were also asked to

briefly describe how they included or considered each

stakeholder or their interest when developing their green

product. In this way the US marketers provided detailed

information on specific approaches that had been used

to address stakeholders in the green NPD process.

The second sample was collected as part of a larger

study, where members of the Australian Marketing Institute in New South Wales were sent a survey relating to

stakeholder theory and its applicability to marketing.

Part of the survey asked respondents to evaluate a set of

eight stakeholders (competitors, customers, employees,

government, owners/ stockholders, special interest

groups, suppliers, top management) regarding a hypothetical scenario, in which they were responsible for the

development of a green product. The questions used to

evaluate stakeholders’ influence were similar to those

administered to US marketers. Given that this sample

was based on a hypothetical scenario, a smaller set of

stakeholders was examined and respondents were not

asked to rate stakeholders’ importance or provide a discussion of processes used to include stakeholders in the

green NPD process.

4. Results

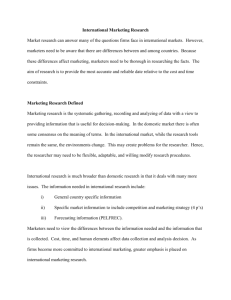

The quantitative results of the survey are summarised

in Table 1. This lists the mean value for US respondents

for the question relating to stakeholders’ overall importance to the green NPD process (column 1), the mean

value of stakeholders’ ability to influence organisational

outcomes for both samples (columns 2–4), and the number of influencing abilities for which there was general

agreement between the two samples (column 5). The

lower the mean value, the higher the perceived influence

and importance; mean values of less than 3.5 are classified as high (H) and mean values equal to or greater than

3.5 are classified as low (L).

The US data represents responses from six of the 15

272

M.J. Polonsky, J.A. Ottman / Journal of Cleaner Production 6 (1998) 269–275

Table 1

US and Australian marketing managers’ perceptions of stakeholders’ importance and involvement; mean response and level: ⬍ 3.5 ⫽ high (H),

ⱖ 3.5 ⫽ low (L)

Stakeholder group

a

Academics/scientific

community

Competitors

Employees/unions

End customers

a

Federal government

a

Local community

a

Media

a

Retailers/trade

Shareholders/owners

Special interest

groups

State and local gov.

Suppliers

Top management

a

1. Importance 2. Direct threatening ability

USA

USA

6.3 L

5.0 L

3.8

4.7

1.5

6.2

5.7

5.5

2.3

3.8

6.2

3.7

5.8

3.3

2.5

5.7

3.7

1.8

3.7

4.7

L

L

H

L

L

L

H

L

L

5.7 L

3.3 H

3.0 H

L

Lb

Hb

H

L

L

H

L

L

4.0 L

2.8 H

1.8 Hb

AUST

3. Direct cooperating ability

4. Indirect influencing ability 5. Consistency

in influencing

abilities

(columns 2–4)

USA

USA

AUST

3.7 L

2.6 H

3.5 Lb

2.5 Hb

Lb

L

Hb

L

L

H

H

Lb

L

3.3 H

3.3 H

4.8

4.3

2.8

4.7

6.3

1.7

1.7

5.0

4.8

3.3 H

3.7 L

2.2 Hb

5.5 Lb

3.5 L

2.3 Hb

AUST

3.8 H

4.7 Lb

2.6 H

2.3 Hb

Hb

L

Hb

L

L

H

H

Lb

L

2.4 Hb

3.4 H

2.0 Hb

2 of 3

1 of 3

3 of 3

3.5 L

2.9 H

3.2

5.7

3.3

4.0

5.5

1.7

1.8

4.5

4.7

3.9 L

2.5 H

2 of 3

0 of 3

3.6 Lb

3.3 H

2.2 Hb

4.8 L

4.8 Lb

4.3 L

3.0 H

3.8 Lb

2.8 H

1 of 3

1 of 3

2 of 3

These stakeholders were not examined by the Australian sample.

Australian and US managers’ perceptions are consistent in regard to this stakeholder’s influencing ability.

b

US marketing managers (40% response rate) whose products won Environmental Edison Awards between 1992

and 1996. One responding company did not provide strategies (i.e. they did not complete the open-ended

questions) and one non-responding firm, who had won

the award twice, indicated that the information asked for

was confidential. Thus, there may, in fact, be some nonrespondent bias, as some firms may have implemented

detailed processes for dealing with their stakeholders,

but were not willing to communicate them to the authors.

When rating the importance of stakeholders (column

1) to the green NPD process, US managers felt that four

of the 13 stakeholders were important (end consumers,

retailers, suppliers, top management), which represents

three of the eight stakeholder groups that were examined

in both samples. US respondents also felt that six of the

stakeholders (scientific community, employees, local

community, owners, special interest groups, local

government) had a low influencing ability for all three

criteria (columns 2–4). The US respondents identified

that competitors, federal government and suppliers were

‘high’ on only one influencing ability. Their attitude

towards suppliers was interesting, as it would be

expected that ‘important’ stakeholders would also have

a substantial influencing ability. Of the remaining four

stakeholders, the media and top management were rated

as ‘high’ on two influencing criteria. End consumers and

retailers were rated as ‘high’ on all three influencing

abilities and were also rated as important to the green

NPD process.

The Australian sample was based on a survey of 1370

members of the Australian Marketing Institute (119

responses, 8.77% response rate). While respondents

were given the opportunity to provide additional stakeholders to this list, only nine ‘additional’ stakeholders

were identified, with none suggested by more than five

respondents. A statistical examination of early and late

respondents indicated that there was no non-response

bias.

In contrast to the US sample, on average, the Australian respondents rated all stakeholders as ‘high’ on at

least one of the three influencing abilities (columns 2–

4). Only two stakeholders are evaluated as ‘low’ on two

influencing abilities, owners (‘low’ on cooperate and

indirect influence) and suppliers (‘low’ on threat and

indirect influence). It appears that Australian marketers

believe that all eight stakeholders can influence the

development and marketing of green products, as all are

rated as ‘high’ on at least one criterion. Consequently,

these groups’ interests should be addressed in the new

product process, and one might expect that they would

participate in the green NPD process.

An examination of column 5 of Table 1 suggests that

there is broad agreement across samples regarding

respondents’ perceptions of stakeholders’ influencing

abilities. Of the eight stakeholders common to both

samples, there was agreement on at least two of the three

dimensions for half the groups. For example, respondents in both samples felt that consumers had a high

level of all three influencing abilities. While respon-

M.J. Polonsky, J.A. Ottman / Journal of Cleaner Production 6 (1998) 269–275

dents’ views are not identical, they are consistent for half

the items (12 of 24). When disagreement does occur, US

marketers who had developed green products believed

that the various stakeholders were less influential in the

green NPD process than their Australian counterparts.

In examining the detailed responses relating to specific strategies used to address stakeholders’ interests

(US sample only as Australians were not asked this

question), few concrete suggestions were put forward.

Most of the suggested strategies were generalist in nature

and broadly related to monitoring and understanding the

wider business environment. For example, regarding the

federal government, one respondent stated ‘FTC marketing advertising guidelines are the only place we pay

attention.’ In addition, the broad strategies that were suggested did not focus on the ‘important’ stakeholders. For

example, there were no suggestions made for dealing

with top management, and those relating to suppliers

were less than innovative (i.e. ‘we rely on them for

raw materials’).

Given that these products are supposed to have an

environmental ‘advantage’ over competing products, the

researchers would have expected that firms would have

actively involved stakeholders with appropriate scientific

and/or environmental expertise. In the US sample, three

of the six respondents suggested that they ‘actively’

worked with the scientific/academic community to

develop their products and none of the respondents suggested that they worked with environmental groups, who

are supposedly environmental experts, to develop the

firm’s products.

This is not to suggest that marketers did not involve

any stakeholders in the green NPD process. For example,

one firm suggested that it was their employees’ innovations that motivated the product’s development, and

another two stated they liked to involve employees in

the development process when possible. All the respondents also suggested that final customers were very

important and they tried to identify their needs and work

with them when possible. Two respondents went even

further and suggested that customers need to understand

the products’ environmental benefits. This suggests that

the firms may not be simply reacting to the business

environment, but may be proactive in their activities and

try to shape stakeholders’ perceptions.

While not found within the study, the literature and

popular press report many cases were firms work with

stakeholders in a range of ways to develop less environmentally harmful products. While respondents did not

suggest that they extensively involve external stakeholders with environmental expertise in the green NPD

process, there are many other firms who appear to be

taking such approaches. These include: hiring environmental stakeholders as consultants [24]; forming task

forces combining firms and green groups [12];

developing strategic alliances with green groups [13,14];

273

having stakeholders undertake lobbying to change regulations; or simply opening the tendering process to

include green groups [13].

5. Implications and conclusions

The results of this study suggest that marketers are

not necessarily learning from others (even competitors)

who are developing green products. Another possibility

is that firms are in the beginning of the greening process

and do not require external participation to make real

environmental improvements and thus develop an

environmental competitive advantage [1]. But as firms

further develop their greening activities, they will require

additional expertise to enable more substantial environmental improvements. Alternatively, it might be that

some of these activities are occurring, but are outside

the domain of marketing. If the latter suggestion is true,

it implies that marketers are not as integral to the NPD

process as the literature suggests.

From the two samples it appears that, overall, marketers believe the stakeholders examined have varying

abilities to influence the development of green products.

Consequently, it would therefore be expected that all

environmental stakeholders would be involved in the

green NPD process. However, based on the US

responses, it does not seem that marketers actively

involve these or any other groups in the green NPD process and, thus, it is unclear if the ‘green’ products on the

market are as environmentally benign as they could be.

Some marketers are attempting to ‘involve’ stakeholders in the green NPD process, by adapting their

firm’s behaviour to address stakeholders’ interests.

While on the surface this may seem to suggest that firms

have a market-oriented approach to product design, it

assumes that the stakeholders’ ‘interests’ are indeed the

most environmentally appropriate. But what if the stakeholders are wrong? For example, because of consumer

concern over greenhouse gases, McDonalds replaced its

polystyrene clamshell packaging with coated paper

[13,14]. However, there has been some scientific debate

whether this was environmentally a better decision. For

Mcdonalds it was easier to modify their behaviour to

address consumers’ interests, rather than to change consumers’ attitudes towards polystyrene.

Thus, ‘listening’ to a given stakeholder group may be

a reactive strategy, whereas working with stakeholders

to identify appropriate solutions may ensure that key

environmental issues are identified and addressed. There

are several examples where firms have worked with

green groups to develop less environmentally harmful

products [12–14,22]. In these cases the solutions do not

simply address a key stakeholder’s interests, but rather

they consider alternatives that address all groups’ objectives. Such an approach requires that stakeholders are

274

M.J. Polonsky, J.A. Ottman / Journal of Cleaner Production 6 (1998) 269–275

formally integrated into the green NPD process and not

considered as an external force. In this study none of the

strategies suggested by US marketers indicated that they

use an integrative approach to green NPD.

This study highlights that, while marketers in the US

and Australia believed various stakeholders were

important to the green NPD process, these stakeholders’

interests were not formally included in the green NPD

process. Some of the approaches suggested by US marketers suggest that they do not work in total isolation.

For example, one firm suggested they work with the

scientific community and another suggested they work

with their employees to develop green products. However, working with stakeholders may be different than

addressing their needs, especially if ‘working with’

means hiring these groups as employees and/or paid consultants. A cooperative approach would hopefully ensure

that the objectives of external stakeholders and the firm

are met. As such, a process requires that there is extensive formal communication between the parties and not

simple reaction on the part of the firm to some perceived ‘problem’.

None of the US respondents suggested that they use

innovative cooperative arrangements. As mentioned

earlier, such practices include having firms working with

stakeholders who have environmental expertise to solve

specific business problems. Interestingly, the US respondents did not believe that any of these ‘environmental

experts’ (governmental bodies, special interest groups,

scientific community) had a ‘high’ ability to influence

the green NPD process and might explain why they were

not involved. On the other hand, the Australian respondents reported that all these environmental experts could

significantly affect the firms’ green NPD process

(although this was in relation to a hypothetical scenario).

Cooperative arrangements not only ensure products

are less environmentally harmful, but have added benefits [10] that include additional credibility in the marketplace and improvement of others’ perceptions of the

firms and their products [13]. None of the respondents

suggested that stakeholders could proactively be used to

influence others in this way. This result is especially surprising given the fact that respondents believed many of

the stakeholders examined (6/8 in the Australian and

4/13 in the US) had a ‘high’ indirect influencing ability.

This is especially surprising given that this practice has

previously been successfully used by many other organisations. Thus, it appears that the respondents are not

learning from others operating in the green product area.

One would have expected that firms which had won a

green product award would be leaders, both in the development of green products and in the application of strategies to facilitate their development. Although, as was

suggested earlier, this might simply mean that firms are

making the ‘easy’ environmental improvements and thus

do not need external expertise, but will need it in the

future when they tackle the more substantial environmental problems [1].

Firms are not the only ones to benefit from these

alliances, as the resulting products and marketing programmes educate consumers and the wider population

on specific environmental issue/problems and solutions.

In addition, the alliance partners may undertake part of

the firm’s work by educating potential consumers on the

green product’s specific environmental benefits. In this

way cooperation helps the firm and its stakeholders in

achieving their objectives.

While it appears that marketers realise the importance

of some stakeholders in the development of green products, it is unclear if marketers actively involve many,

if any, of these stakeholders. Furthermore, it is not clear

that those involved in the green NPD process are

included in the most effective fashion. From this study,

it appears that firms simply try to adopt to stakeholders’

interests. Such a process may seem to be market-oriented. However, by not interacting with their stakeholders, some benefits are potentially overlooked. These

include involving these stakeholders in the marketing

process and achieving stakeholders’ objectives and

environmental objectives as well.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this work have been presented at

the International Association of Business and Society

Eighth Annual Conference 1997 and the Eighth Biannual

World Marketing Congress 1997. We would also like to

thanks Professor D. Huisingh, Gary Mankelow and the

anonymous reviewers at JCP for their useful feedback

in the revision of this work.

References

[1] Porter ME, Van Der Linde C. Green and competitive: ending the

stalemate. Harvard Business Review 1995;73(5):120–34.

[2] Menon A, Menon A. Enviropreneurial marketing strategy: the

emergence of corporate environmentalism as market strategy.

Journal of Marketing 1997;61(1):51–67.

[3] Clair JA, Milliman J, Whelan K. Toward an environmentally

sensitive ecophilosphy for business management. Industry and

Environmental Crisis Quarterly 1996;9(3):289–326.

[4] Urban GL, Hauser JR. Design and marketing of new products.

Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1993.

[5] Bhat VN. Green marketing begins with green design. Journal of

Business and Industrial Marketing 1993;8(3):26–31.

[6] McDaniel SW, Rylander DH. Strategic green marketing. Journal

of Consumer Marketing 1993;10(3):4–10.

[7] Anonymous. Spurts and starts: corporate role in ’90s environmentalism hardly consistent. Advertising Age 1991;62(46):GR14–6.

[8] Polonsky MJ. A stakeholder theory approach to designing

environmental marketing strategy. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing 1995;10(3):29–46.

M.J. Polonsky, J.A. Ottman / Journal of Cleaner Production 6 (1998) 269–275

[9] Ottman JA. Mandate for the 90s: ‘green corporate image’. Marketing News 1995;29(29):8.

[10] Ottman JA. Edison award for corporate environmental achievement. Marketing News 1996;30(10):15.

[11] Bendell J, Murphy D. Strange bedfellows: business and environmental groups. Business and Society Review 1997;98:40–4.

[12] Lober DJ. Explaining the formation of business–environmentalist

collaborations: collaborative windows and the paper task force.

Policy Sciences 1997;30(1):1–24.

[13] Mendleson N, Polonsky MJ. Using strategic alliances to develop

credible green marketing. Journal of Consumer Marketing

1995;12(2):4–18.

[14] Stafford ER, Hartman CL. Green alliances: strategic relations

between businesses and environmental groups. Business Horizons

1996;39(2):50–9.

[15] Cooper RG, Kleinschmidt EJ. An investigation into the new product process: steps, deficiencies and impact. Journal of Product

Innovation Management 1986;3(1):71–85.

[16] Karakaya F, Kobu B. New product development process: an

investigation of success and failure in high-technology and nonhigh technology firms. Journal of Business Venturing

1994;9(1):46–66.

[17] Millson MR, Raj SP, Wilemon D. Strategic partnering for

[18]

[19]

[20]

[21]

[22]

[23]

[24]

275

developing new products. Research–Technology Management

1996;29:41–9.

Lamb W. From experience: building balanced innovation teams.

Journal of Innovation Management 1985;2:93–100.

Prasad L, Rubenstein AH. Power and organizational politics during new product development: a conceptual framework. Journal

of Scientific and Industrial Research 1994;53(6):397–407.

Harrison JS, St John CH. Managing and partnering with external

stakeholders.

Academy

of

Management

Executive

1996;10(2):46–60.

Polonsky MJ. Stakeholder management and the stakeholder

matrix: potential strategic marketing tools. Journal of Market

Focused Management 1996;1(3):209–29.

Westley F, Vredenburg H. Strategic bridging: the collaboration

between environmentalists and business in the marketing of green

products.

Journal

of

Applied

Behavioral

Science

1991;27(1):65–90.

Kreiner P, Bhambri A. Influence and information in organisation

stakeholder relationships. Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy 1991;12:3–36.

Ottman JA. Private groups, government act as consultants. Marketing News 1996;30(10):15.

![Your [NPD Department, Education Department, etc.] celebrates](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/006999280_1-c4853890b7f91ccbdba78c778c43c36b-300x300.png)