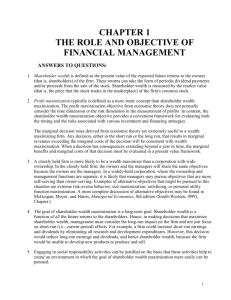

Shareholder Wealth Maximization and its

advertisement