Mixed jurisdictions : common law vs civil law (codified and

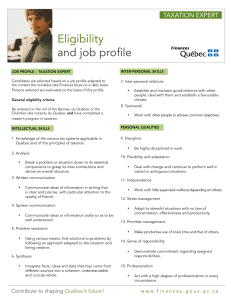

advertisement