View PDF - Oklahoma Water Policy

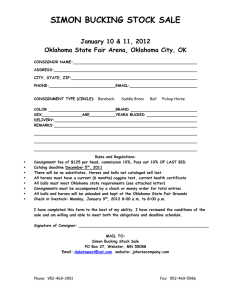

advertisement

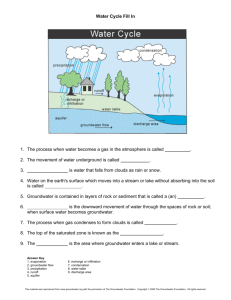

WATER LAW, WATER RIGHTS, HYDROPOLITICS PRIMER DRAFT Property of Richard Wheatley Company LLC OVERVIEW Groundwater Rights The Rule of Capture provides each landowner the ability to capture as much groundwater as they can put to a beneficial use, but they are not guaranteed any set amount of water. The advantage of this system is that it encourages economic development and maximum utilization of the resources. Another advantage of this system is that it leads to minimal government involvement in the operation of water wells. The primary disadvantage of this system is the potential for overproduction of the aquifer system that may result when each land owner attempts to protect the water right by drilling bigger, deeper wells. Because no landowner is given a quantifiable or set amount of production capacity, all landowners are encouraged to capture as much water as they can as quickly as they can. Riparian Rights Correlative groundwater rights represent limited private ownership rights similar to riparian rights in a surface stream. The amount of groundwater right is based on the size of the surface area which each landowner gets a corresponding amount of available water. Once adjudicated, this maximum of water right is set, but this right can be decreased if the total amount of available water decreases s is likely during a drought. Landowners may sue others for encroaching upon their groundwater rights and water pumped for use as on the overlying land takes preference over water pumped for use off the land. This system benefits those who have low demand for water buy own large expanses of property – such as ranches – and harms those who have a high demand for water without correspondingly large tracts of land – such as cities and some irrigators. Only California follows the correlative rights system for groundwater. Reasonable Use Rule The third system involving private ownership rights is the liability rule known as the American Rule or Reasonable Use Rule. This rule does not guarantee the landowner a set amount of water, but allows unlimited extraction as long as the result does not unreasonably damage other wells of the aquifer system. Usually this rule gives great weight to historical uses and prevents new uses that interfere with the prior use. The determination of who gets a well and how much water may be pumped is usually made by a court unless the state creates a regulatory agency to perform that function and the primary issue is “reasonableness” of the use. The advantage of this system is its flexibility in adjudicating competing uses of an aquifer system. Unfortunately, this same system can lead to excessive litigation because well owners may sue at any time to determine if a competing use is “reasonable,” a standard that may change with time. The reasonableness standard is also highly dependent on the location of the suit and who ends up in the jury pool. Marketing rights does not take place until the system is fully adjudicated’ new users do not purchase groundwater rights until they are sure they cannot obtain “free” water through litigation. Many states, especially in the western United States, claim ownership of groundwater and allocate the resource through an appropriative system just as they would a surface right. Typically water rights are appropriated based on each aquifers sustainable yield and once all rights are granted no further permits will be issued. Some states allow the permits to be marketed and some states do not. When the water is not owned by the state and the tort law proves be an inadequate means to prevent over production, states have created administrative regulatory agencies to allocate ground water rights between competing landowners. In this case the administrative law essentially supplants the tort law, making the tort remedy (or lack thereof) irrelevant. OKLAHOMA VIEW Surface/Stream Water Rights Water Allocation and Ownership Oklahoma’s early territorial lawmakers adopted the English Water Law Doctrine known as “Natural Flow.” The natural flow doctrine has two primary components (1) a prohibition against changing the quantity of water flowing in a stream and (20 a prohibition on polluting a stream. The owner of land owns water standing thereon or flowing over or under its surface but not forming a definite stream. Water running in a definite stream, formed by nature over or under the surface may be used by him as long as it remains there, but he may not prevent the natural flow of the stream or the natural spring from which it commenced its definite course, nor preserve nor pollute the same. The natural flow doctrine distinguished waters flowing on the surface but not forming a definite stream from water forming a “definite stream.” The concept of “definite stream” is still important in Oklahoma water allocation law because, as with the natural flow doctrine, the owner of the land still owns the surface water which is not a “definite stream,” A landowner has the right under Oklahoma law to do whatever he wills with this surface water because he absolutely owns it, However, if the water forms a definite stream this landowner may be required to obtain permission of the Oklahoma Water Resources Board (OWRB) to use the water. The land owner may also have a “riparian right” to reasonably use water from a stream which runs upon or about his land. The natural flow doctrine adopted by the territorial legislature was completely impractical because it did not allow for consumptive uses. Most economically beneficial uses are consumptive, so the natural flow doctrine was a hindrance to economic development and was quickly abandoned in favor of the “reasonable use” doctrine. The “reasonable use” doctrine allows a landowner whose land abuts a river (called a riparian) to make reasonable use of water so long as use does not unreasonably interfere with reasonable use of anther riparian landowner. To keep this confusing, the reasonable use doctrine is more commonly referred to as the “riparian doctrine” or “riparianism.” Riparianism remains an important principal in the law of water in Oklahoma today. While riparianism was developing in Oklahoma, another doctrine known as “prior appropriation” was also developing. Prior appropriation gives the senior user of water superior rights – first in time first in rights. Under prior appropriation, the first user to put water to use economically, beneficial use has a superior right to his allocation of water in case of a shortage. Theoretically, under riparianism, all similar riparian users would be cut back proportionally (i.e. reasonably) in times of shortage. Under prior appropriation doctrine the senior user could completely shut off water to the junior user to ensure that the senior user r3eceived his entire allocate amount of water. In 1963, the Legislature attempted to reconcile these two systems of water allocation by allowing OWRB to bring suit in district court to adjudicate the priorities to water in the states stream systems. Any rights to use water which were not asserted at these proceedings were foreclosed. However the Legislature did leave a small remnant of riparianism which allowed a riparian landowner to use water for domestic and household purposes. The fundamental rule in Oklahoma however became “Prior Appropriation” under which each person knew the quantity of water to which he was entitled and his priority among water users on a given stream system. Franco-American Charolaise LTD v Oklahoma Water Resources Board which held that adjudication to determine water priorities unconstitutionally took riparian owners vested water rights without just compensation shattered any sense of clarity which the 1963 adjudication of rights had provided. What is clear is that water deals will now have to account for the possibility of a riparian owner asserting previously unused riparian rights. Riparian landowners arguably do not have to apply for a permit to put stream water to use. The riparian owner could merely begin using the water subject to later court decision that the use is “unreasonable.” Groundwater Allocation Anyone proposing to use groundwater except for domestic purposes must apply for an appropriate permit. The landowner must demonstrate a beneficial use which dos not constitute waste. If the landowner does this the landowner must be given an allocation of groundwater. The amount of groundwater which a landowner can use is proportional to the maximum annual yield of the formation according to the following formula. “His proportionate share shall be that percentage of the total annual yield of the basin or subbasin, previously determined to be the maximum annual yielded …. Which is equal to the percentage of land overlying the ???? groundwater basin of subbasin which he owns or leases.” Four types of groundwater allocation permits are available. (1) regular, (2) temporary, (3) special, (4) provisional temporary. (4) is available only for 60 days and is nonrenewable but can be granted immediately by OWRB. The regular permit can only be issued after OWRB has completed a hydrologic survey of the formation from which the water is to be drawn. To date only a few of the "major” groundwater formations in Oklahoma have been surveyed. Until the hydrologic surveys are completed for a given formation, only “temporary” permits can be issued. However these nominally temporary permits are renewed annually. Two sweeping federal laws asserted control over all waters of the country. The Clean Water Act and the Safe Drinking Water Act. The Environmental Protection Agency was given the authority to enforce theses acts. Because of the “local” nature of water, substantial regulating, enforcement and permitting powers were delegated to the states. As a result, the Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality, the Oklahoma Water Resources Board, the Oklahoma Department of Agriculture, Food and Forestry, the Oklahoma Corporation Commission and the Oklahoma Department of Mines control the use of water. Other waters of the state are impounded in lakes owned and operated by either the Wildlife Department, cities, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the Grand River Dam Authority, the Division of State Parks, the U.S Forest Service or the Oklahoma Gas and Electric Company. The State of Oklahoma is a party to four interstate stream compacts involving all the surface water that flows into or out of Oklahoma. Those compacts are: the Canadian River Compact, the Kansas-Oklahoma-Arkansas River Compact, the ArkansasOklahoma-Arkansas River Compact and the Red River Compact. All uses of surface and groundwater in Oklahoma for other than domestic/household purposes must be permitted by the OWRB GROUNDWATER use is a legal property right tied to ownership of the land. Applicants must satisfy four legal requirements in order to obtain a groundwater permit. • The applicant owns or leases the land from which the water will be drawn. • The dedicated land overlies a groundwater basin. • The water will be put to beneficial use. • Waste of the water will not occur. SURFACEWATER is publicly owned. Before permitting its use, the OWRB must determine that: • Unappropriated water is available in the amount applied for. • The applicant has a present or future need for the water. • The applicant intends to put the water to a beneficial use. • The proposed use would not interfere with domestic/existing appropriative uses. • If use of the water is to occur outside the stream system of origin, it would not interfere with existing or proposed beneficial uses within the stream system. OKLAHOMA WATER FACTS (Courtesy of OWRB) • Oklahoma has approximately 78,500 miles of rivers and streams. • Oklahoma contains approximately 1,120 square miles of water in its lakes and ponds. • Oklahoma has approximately 11,600 miles of shoreline. • The Ogallala aquifer contains about 87 million acre feet of water in storage. The aquifer supports approximately 3,200 high capacity wells and 206,000 acres of irrigated land. • Irrigation, is the number one use of water in Oklahoma, water supply is second followed by livestock watering. • The majority of the state’s surface water (approximately 60 per cent) is used for public water supply, followed by thermoelectric power generation and irrigation. • Irrigation accounts for 72 per cent of Oklaoma’s groundwater withdrawals. • An estimated 34 million acre-feet of water (11 trillion gallons flows out of the state each year through Oklahoma’s two major river basins, the Red and the Arkansas. Approximately 18 times the states total annual water usage. • One acre-foot of water (the amount of water required to cover one acre of land to a depth of one foot) equals 325,851 gallons or 43,560 cubic feet. Your source for permitting. Oklahoma Water Resource Board (OWRB) Oklahoma Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) Oklahoma Corporation Commission (OCC) Oklahoma Department of Mines (ODM)