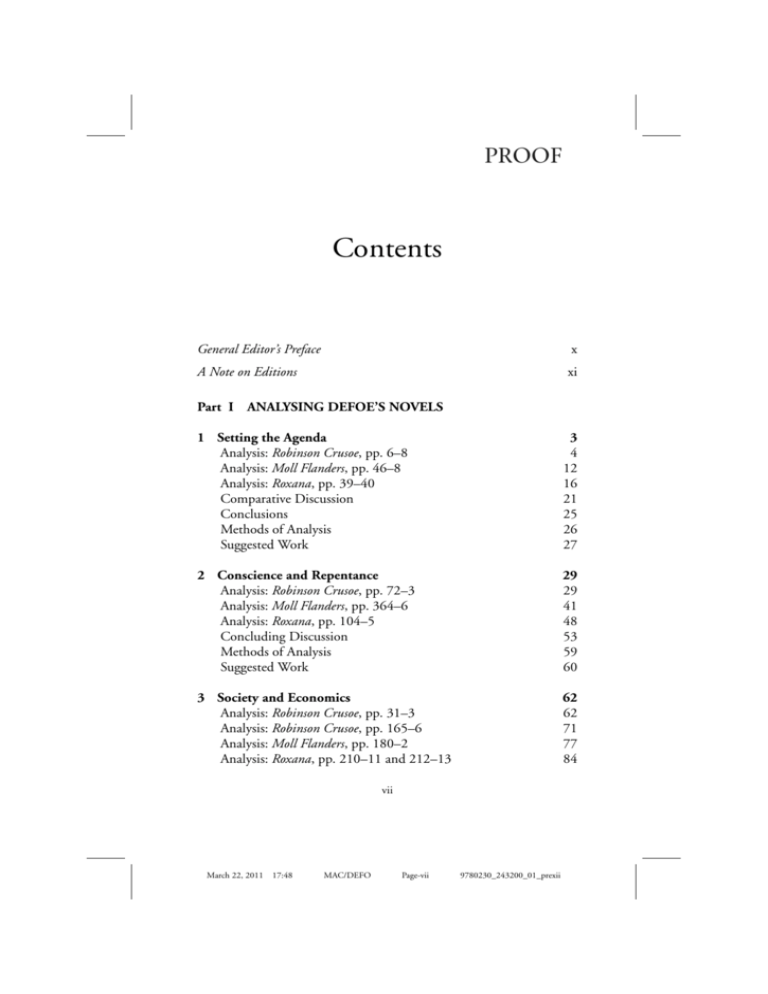

Contents - Palgrave Higher Education

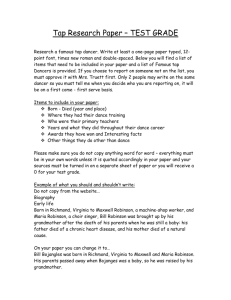

advertisement