Branding Children: Marketing Techniques

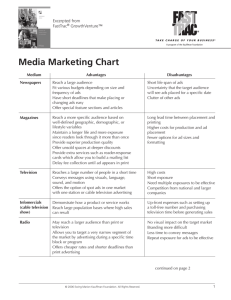

advertisement