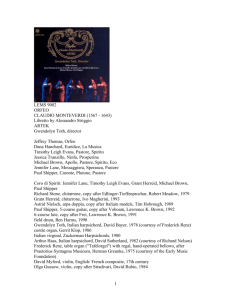

L'Orfeo Booklet

advertisement

476 2879 476 8030 L'Orfeo Favola in Musica Claudio Monteverdi Pinchgut Opera Tucker ❙ Macliver Whiteley ❙ McMahon Weymark ❙ Mills ❙ Fraser Cantillation Orchestra of the Antipodes Walker ANTIPODES is a sub-label of ABC Classics devoted to the historically informed performance of music from the Renaissance, Baroque and Classical periods. L'Orfeo Favola in Musica Music by Claudio Monteverdi 1567-1643 Libretto by Alessandro Striggio c.1573-1630 L’Orfeo was first peformed at the court of Duke Francesco Gonzaga in Mantua, 1607. This edition by Erin Helyard. Mark Tucker Sara Macliver Damian Whiteley Paul McMahon Brett Weymark Penelope Mills Josie Ryan Anna Fraser Paul McMahon/Brett Weymark, Jenny Duck-Chong, David Greco, Philip Chu, Craig Everingham, Belinda Montgomery, Raff Wilson, Daniel Walker Benjamin Loomes, David Greco Orfeo (Orpheus) La Musica (Music), Messaggiera (Messenger), Proserpina (Persephone) Caronte (Charon), Plutone (Pluto) Apollo Eco (Echo) Euridice (Eurydice) Ninfa (Nymph) Speranza (Hope) Pastori (Shepherds) Spiriti infernali (Spirits of Hell) Cantillation Orchestra of the Antipodes (on period instruments) Antony Walker conductor 3 CD1 [49’27] 1 Toccata 1’58 PROLOGO 2 Ritornello...Dal mio Permesso amato 6’16 La Musica % Mira, deh mira, Orfeo...Ahi, caso acerbo! 3’35 Pastore I, Messaggiera, Pastore VIII, Orfeo ^ In un fiorito prato...Ahi, caso acerbo! 4’05 Messaggiera, Pastore I & IV & Tu se’ morta 2’27 Orfeo ATTO PRIMO 3 In questo lieto e fortunato giorno Pastore I 1’34 4 Vieni Imeneo, deh vieni...Muse honor di Parnasso 1’40 * Ahi, caso acerbo!...Ma io ch’in questa lingua 4’14 Choro, Messaggiera ( Chi ne consola, ahi lassi? 2’02 Pastori I & VII Choro, Ninfa 5 Lasciate i monti...Ma tu, gentil cantor 2’19 ) Ahi, caso acerbo!…Ma dove, ah dove hor sono 4’13 Choro, Pastori I & VII Choro, Pastore II 6 Rosa del ciel...Io non dirò qual sia 3’03 CD2 1’30 ATTO TERZO 1 Sinfonia 1’34 2 Scorto da te mio Nume 1’25 Orfeo, Euridice 7 Lasciate i monti…Vieni Imeneo, deh vieni Choro 8 Ma s’il nostro gioir 1’23 Pastore III [62’36] Orfeo 3 Ecco l’atra palude 9 Alcun non sia 1’17 Pastori I & IV 3’02 Speranza 4 Dove, ah dove te’n vai...O tu ch’innanzi mort’a queste rive 0 Che poi che nembo rio 1’20 Pastori I, II & V 5 Possente Spirto ! E dopo l’aspro gel...Ecco Orfeo 1’19 Pastori VI & VII, Choro 6’17 Orfeo 6 Orfeo son io ATTO SECONDO @ Sinfonia...Ecco pur ch’à voi ritorno Orfeo 0‘49 £ Mira, ch’à se n’alletta...Dunque fà degno Orfeo 2’03 3’18 Orfeo, Caronte 3’07 Orfeo 7 Ben mi lusinga alquanto...Ahi, sventurato amante!...Sinfonia 2’45 Caronte, Orfeo Pastori I & IV, Choro 8 Ei dorme, e la mia cetra Orfeo $ Vi ricorda ò boschi ombrosi 2’16 Orfeo 4 5 2’09 9 Sinfonia a 7...Nulla impresa per huom 0 ! @ £ $ % ^ & * ( ) ¡ ™ # 4’04 Choro ATTO QUARTO Signor, quel infelice Proserpina Benchè severo ed immutabil fato Plutone O degli habitator de l’ombre eterne Spiriti I & II Quali grazie ti rendo...Tue soavi parole Proserpina, Plutone Pietade oggi et Amore...Ecco il gentil cantore Choro, Spirito I Ritornello...Qual honor di te fia degno...Rott’hai la legge Orfeo, Spirito II Ahi, vista troppo dolce...Torn’a l’ombre di morte Euridice, Spirito I Sinfonia a 7...È la virtute un raggio Choro ATTO QUINTO Ritornello...Questi i campi di Tracia Orfeo, Eco Ma tu anima mia Orfeo Perch’a lo sdegno...Padre cortese Apollo, Orfeo Saliam cantand’al cielo Apollo, Orfeo Vanne, Orfeo, felice a pieno Choro Moresca 1’26 Total Playing Time 112’03 6 2’49 2’12 1’09 1’57 0’42 3’22 2’05 3’56 5’10 3’59 3’49 1’12 1’01 Francesco Rasi, took it to the archbishop’s court at Salzburg where it was performed regularly between 1614 and 1619; and there were performances in Genoa and elsewhere in the Italian peninsula right up to the 1650s, when the work itself was now forty years old. What was it about L’Orfeo that ensured its place on the stage, and how did Monteverdi become so deliberately associated with the music of a new generation, having brought ‘new life’ to ‘theatrical music’? ‘Authenticity’ in Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo The canonising of Monteverdi and his music was a cultural process well under way by the 1640s, when the composer was in his seventies, lauded and celebrated in Venice. The unknown librettist of a now lost setting of Le nozze d’Enea in Lavinia (1640-41) wrote this encomium in the preface to the printed libretto: To this truly great man, this most noble art of music – and particularly theatrical music – knows itself to be so much in debt that it can confess that it is thanks to him that it has been brought to new life in a world more efficacious and perfect than it was in ancient Greece … For this Signor Monteverde [sic], known in far-flung parts and wherever music is known, will be sighed for in future ages, at least as far as they can be consoled by his most noble compositions, which are set to last as long as can resist the ravages of time any more esteemed and estimable fruit of one who is a wondrous talent in his profession. L’Orfeo was described at the time as a favola in musica (literally, a ‘musical fable’), and it heralded the beginning of the dissemination of a new theatrical or ‘representative’ style (stile rappresentativo) – a synthesis coaxed from the intellectual, philosophical and aesthetic discussions of the Florentine Academies and the older, more traditional dramatic models of the madrigal and intermedio. In what might be described as a searching for ‘authenticity’ in music (a concept that might strike us today as curiously modern), the debates of Florentine intellectuals in the late 16th and early 17th centuries led them, in their conscious search for newer musical forms and style, to review the world of ancient Greece, believing that the rendering of poetry into natural speech-like rhythms (which was understood to have been Greek practice) would create a new music wholly responsive to the needs of theatre. It was to be ‘authentic’ musical theatre – authentic In the case of L’Orfeo, it seems that Prince Francesco Gonzaga, who had organised the first performance, was already planning a repeat performance in Casale Monferrato (where he was governor) in Carnival 1609-10, not long after the Mantuan premiere in 1607; there were two printed editions of the music, an unusually lavish feat; the original Orfeo, the acclaimed tenor 7 as in the Greek authentikos, ‘of first-hand authority, original’. One of the many novel textures associated with the style was stile recitativo, a single sung line supported by chordal instruments that partly evoked the ancient instrumental conventions of lyre and kithara (lirone, chitarrone and so on). Monteverdi combined his skill as a madrigal composer with experiments in the new style to set Alessandro Striggio’s L’Orfeo for a Carnival entertainment for the Mantuan court in 1607. moreover, observing due propriety, serves the poetry so well that nothing more beautiful is to be heard anywhere. Ferrari’s deliberate evocation of three traditional pillars of Greek and Roman oratory – inventio (invention), dispositio (arrangement) and elocutio (style) – subtly acknowledges the ‘authenticity’ exemplified in this new or ‘second’ style (seconda pratica), with its emphasis on neoPlatonic ideals that music (harmonia and rhythmos) should follow the demands of the text, or original idea (logos). This particular favola in musica was understood to have reconciled and merged, in a unique and masterly manner, contrary and conflicting dramatic concerns (speech/song; realism/artifice; declamation/conversation; chorus/soloist and so on) – concerns that were to fascinate Monteverdi throughout his career. The Mantuan court theologian and poet Cherubino Ferrari wrote to Duke Vincenzio Gonzaga in August 1607: Striggio’s interpretation of the Orpheus myth owes much to Ovid’s Metamorphoses. The original ending, however, which he replaced with a traditional lieto fine (‘happy ending’), reflects a different narrative tradition. Renouncing the love of women, who are ‘pitiless and fickle, devoid of reason and all noble thoughts’, Orpheus flees the arrival of a group of drunken female revellers – the Bacchantes, disciples of Dionysus. They sing in praise of Bacchus and declare that Orpheus will eventually get the punishment he deserves. In other versions well known to the academicians present at the first performance, Orpheus is murdered and decapitated by the Bacchantes, the head continuing to lament for Eurydice as it floats down the River Hebrus to Lesbos. The final version of Monteverdi’s L’Orfeo, as represented in the two printed editions, ends with a deus ex machina and [Monteverdi] has shown me the words and let me hear the music of the play which Your Highness had performed, and certainly both poet and musician have depicted the inclinations of the heart so skilfully that it could not have done better. The poetry is lovely in conception [inventione], lovelier still in form [disposizione], and loveliest of all in elocution [elecuzione]; and indeed no less was to be expected of a man as richly talented as Signor Striggio. The music, 8 Orfeo’s ascent to heaven with his father Apollo – an ending not incompatible with the more gruesome versions, as it was generally recognised that Orpheus and Eurydice are eventually reunited in Elysium, whatever the earthly fate of the great singer. Two aesthetic entities, not yet reconciled, were being held up for judgment: the libretto (the favola) and the music. The libretto’s Humanistic tone on the perils of earthly love and the abandonment of reason is aptly summed up in the moralistic choruses; Musica herself in the Prologue outlines the central concern of the conjoining of text and music. Carter comments: Concerned with the in musica challenge of the favola, Striggio makes conscious efforts to incorporate musical imagery into the libretto with continual references to singing and dancing, and indeed, it was the sung nature of the drama that surprised and delighted the contemporary audience. ‘It should be unusual, as all the actors are to sing their parts … No doubt I shall be driven to attend out of sheer curiosity,’ wrote Carlo Magno to his brother Giovanni. The Prologue, delivered by Musica, goes straight to the core philosophy of the stile rappresentativo itself: after the obligatory and discreet homage to the Gonzagas (‘renowned heroes, noble blood of kings’) Musica proclaims her ability to calm the soul, to arouse it in anger, to inflame it with love. She invokes the Harmony of the Spheres before she is ‘spurred on by the desire to tell you of Orpheus’. Tim Carter, in his recent work Monteverdi’s Musical Theatre, interprets these neo-Platonic resonances as an invitation to witness and even assess a demonstration of these claims; in a way, Monteverdi and Striggio are putting the ‘representative’ style to the test. Keeping these messages separate resolves the apparent paradox that can cloud any interpretation of Orfeo, that an opera seemingly extolling the power of music should appear to end in failure, saved only by a contrived lieto fine. Orfeo’s failure is not one of eloquence: in effect, Musica gets Orfeo through the gates of Hades. Rather, it is one of moral fibre: Orfeo lacks the ability and experience to control his emotions by way of reason. The extraordinary Act III showpiece (‘Possente Spirto e formidabil nume’), written specifically for Rasi’s agile and formidable voice, fails, in all its heightened ornamental delivery in the grand antique poetics of the terza rima, to move Caronte (Charon), simply because pity, the god says, is not an emotion worthy of his valour. It is only Orfeo’s playing upon his lyre (represented by Monteverdi in a five-part string sinfonia) that sends him to sleep, enabling the musician to pass into Hades, his innate eloquence neither diminished nor vanquished. 9 Pluto’s test to Orfeo is one of virtue – a test he fails when, in his humanity, emotion overcomes reason. Orfeo in Act IV sees Amor as a god more powerful than Pluto; it is only by renouncing earthly love (i.e. Amor) and by embracing Apollo’s offer of the path of true virtue that he can attain the vaults of heaven. As Ovid pointed out, Orpheus’ only sin is that he loved too much. The Act III choruses fulfil the function of an Aristotelian chorus, reminding the audience of three other heroes who defied nature with their art and failed: Daedalus (who attempted to fly – ‘mocking the fury of the South and North winds’ – and lost his son Icarus), Jason (who ‘reaped a golden harvest’ but whose wife Creusa was murdered by Medea) and Phaeton (who tamed the Sun but drowned). Pride comes before a fall, just as it will for Orfeo. spheres of symmetry: the joyful dances and choruses orbiting Orfeo’s ecstatic ‘Rosa del ciel’ in Act I; the strophic refrains of Caronte in Act III; Orfeo’s song of joy at recovering Euridice before the second, fatal, death; his long, moving lament on the plains of Thrace; the final joyous duet with Apollo. Monteverdi’s specific orchestral directions colour the opposing scenes in traditional hues that would become a mainstay of the developing operatic tradition for more than a century to come: sackbuts and the grating regale for the underworld; harpsichords, winds and strings for the shepherds and nymphs; organ and chitarrone for heartfelt soliloquies, and so on. Ferrari placed Striggio’s poetic endeavours squarely within the framework of the rhetorical tradition, leaving to Monteverdi and music in general only the delivery of an ideal oration articulated by the ever-superior librettist. Returning to our anonymous 1640 encomium to the venerable master, we see just how much change had occurred in musical circles towards the reception of theatrical music. The popularity of L’Orfeo seems only attributable to an enthusiastic reception of this new attempt in the stile rappresentativo. The Orpheus myth was a convenient and fitting metaphor for the new efforts at conjoining music, drama and poetry, and the younger progressive princes saw in Monteverdi’s seconda pratica a kind of reflection of their own political innovations. Monteverdi’s setting of the libretto presents elements of recitative and madrigal in uniquely structured ways, artfully combined. Orfeo in all his glorious eloquence stands at the centre with ‘Possente Spirto’ – around him are arrayed other talent, adapting in such a way the musical notes to the words and to the passions that he who sings must laugh, weep, grow angry and grow pitying, and do all the rest that they command, with the listener no less led to the same impulse in the variety and force of the same perturbations. Claudio Monteverdi Claudio Giovanni Antonio Monteverdi was born in Cremona, in 1567. He was the son of a doctor and the eldest of five children. Not much is known about his youth. Claudio and his brother studied music with a Marc Antonio Ingegneri who was the cathedral composer, though there is no evidence that either sang in the choir. And so, by the mid-century, Monteverdi had become Orpheus; the supreme orator, the consummate musician, the inspired genius. In the words of Shakespeare, he: Monteverdi was a prodigy, publishing his first work, Cantiunculae sacrae, a volume of sacred songs, as a 15-year-old. His second book was published the following year and in 1584 his third book was published by the Venetian house which would become his main publisher, Vincenti & Amadino. Three years later, aged 19, he published his First Book of Madrigals. …with his lute made trees, And the mountain tops that freeze, Bow themselves, when he did sing: To his music, plants and flowers Ever sprung; as sun and showers There had made a lasting spring. (Henry VIII, Act III, scene i) In 1592, aged 25, Monteverdi was hired as a viol player to Vincenzo I, Duke of Mantua. Mantua was under the protection of the powerful Gonzaga family, and Monteverdi’s lot depended very much on the character of the ruling duke. The first Gonzaga Duke, Guglielmo, was wise, cultured, educated, talented and progressive; Vincenzo I, Guglielmo’s successor and Monteverdi’s boss, fell short of the ideal Renaissance monarch. An inconsistent, brutish ruler, he did however have a great love for drama and music and kept a stable of virtuoso performers to gratify his passion for display. Erin Helyard Now you, my Lords, tolerating the imperfection of my poetry, enjoy cheerfully the sweetness of the music of the never enough praised Monteverde, born to the world so as to rule over the emotions of others, there being no harsh spirit that he does not turn and move according to his 10 11 Duke Vincenzo promoted Monteverdi from viol player to singer, a much more senior position. The next year Monteverdi was disappointed when the maestro di cappella died and the vacancy was filled by Benedetto Pallavicino, an older, well-published musician whom Monteverdi nevertheless considered his inferior. Despite his own growing fame and the fact that he was the highest-paid court singer – and next in line for promotion – Monteverdi began to feel discontent. He married court singer Claudia Cattaneo in May 1599; when Pallavicino died in 1601, Monteverdi again applied for his position and was awarded the post, the same year that his son Francesco was born. opera. Claudia died in September of that year, after a long illness, and Monteverdi was left a widower with his two surviving children, sons aged six and three. He was 40 years old. He stopped composing, but was coaxed back by a letter promising fame and a prince’s gratitude. He buried his sorrows in work – a new opera (Arianna), an intermezzo and a ballet for the celebration of a royal wedding. Despite extremely stressful working conditions, his music was a great success. However, this could not alter his depression and Monteverdi went home to Cremona in such a collapsed state that his father wrote to the Duchess of Mantua with a request that Claudio be released from his duties. As he became more famous, his music was attacked by Bolognese theorist Giovanni Maria Artusi, who in 1600 and 1603 pointed to Monteverdi as a perpetrator of crimes against music. When the Fifth Book of Madrigals appeared in 1605, perhaps in reply to Artusi, opinion sided with Monteverdi. Not only was this fifth volume reprinted within a year, the publisher also reprinted all of Monteverdi’s earlier books. Two more children were born to Claudio and Claudia, and with their debts mounting, Monteverdi complained about irregular payment of his salary. In 1607 he presented L’Orfeo (commissioned for Carnival at Mantua), but had little opportunity to enjoy the triumph of his first 12 Monteverdi was not one to be left out. Aged 70, Monteverdi’s composing took on a new life. Arianna was revived in 1639 (though was subsequently lost); a series of new works followed, including Il ritorno d’Ulisse in patria. He published his Eighth Book of Madrigals and a collection of church music. In 1642, at the age of 75, he composed L’incoronazione di Poppea. with regularly employed singers, instrumentalists and many others for special events. Music had to be provided – composed, rehearsed, performed – for about forty festivals per year. In his mid-forties, he was in his prime not only in his own composition but also in how he took on his new job. He reorganised the chapel band, brought the choir up to strength, hired more musicians for more services and expanded the music library. After three years he was granted a ten-year contract. He was happy – financially comfortable, famous, appreciated by his employers, and loved by the public. The request was denied and Monteverdi was summoned to return, though with a substantial pay rise. By 1610 he was back in Mantua and obviously casting about for another job. The need to find this became urgent when, in 1612, Vincenzo died; his son Francesco ascended the throne and suddenly dismissed Monteverdi. After more than twenty years of service in the Gonzaga ducal court, Monteverdi returned to Cremona with the equivalent of one month’s salary in his pocket: his life savings. By 1620 Venice was a ferment of music composition – there were six composers employed by the Basilica itself. Monteverdi was in his fifties, secure in his job and venerated at home and abroad. As well as his church composition, he wrote solo motets, duets and other more easily performed works for various anthologies of church music. Heinrich Schütz visited from Germany in 1628 to learn from Monteverdi the new art of opera and church music. In 1630 the plague swept through Venice, killing 40,000 but sparing Claudio. He was worn down by the strain, however, and in 1632 was ordained a priest. The following year the maestro di cappella at San Marco in Venice died. Monteverdi applied for the post and was appointed on the spot. This new job was huge. The Basilica at San Marco was the largest musical establishment in Italy, Just when it seemed that his career was beginning to fade, Venice was evolving into a city of opera. In 1637 the first public opera house opened with Manelli’s Andromeda. Soon after, several others were opened and He died in Venice of a malignant fever on 29 November 1643. The city mourned him with an impressive funeral ceremony held in two churches, San Marco and Santa Maria dei Frari, where he was buried. His publisher Vincenti collected the manuscripts of all his unpublished church music and published them in 1651. Also that year, Poppea was performed in far-away Naples. Like many great composers of the Baroque, Monteverdi’s work was largely neglected after his death and regained full recognition only in the 20th century. Alison Johnston and Ken Nielsen 13 Penelope Mills Mark Tucker Sara Macliver David Greco Philip Chu Damian Whiteley Paul McMahon Brett Weymark Craig Everingham Raff Wilson Belinda Montgomery Josie Ryan Anna Fraser Jenny Duck-Chong Daniel Walker Benjamin Loomes Antony Walker 14 15 CD1 1 2 3 PROLOGO PROLOGUE LA MUSICA Dal mio Permesso amato à voi ne vegno, incliti Eroi, sangue gentil de regi, di cui narra la Fama eccelsi pregi, nè giunge al ver perch’è tropp’alto il segno. MUSIC I come to you from my beloved river Permessus, O great heroes, noble race of kings; Fame sings your splendid qualities, but falls short of the truth, so high is the mark. Io la Musica son, ch’à i dolci accenti sò far tranquillo ogni turbato core, et hor di nobil ira, et hor d’amore posso infiammar le più gelate menti. I am Music, who with sweet accents can calm every restless heart; and, now with noble anger, now with love, can inflame the most frozen minds. Io sù cetera d’or cantando soglio mortal orecchio lusingar talhora e in questa guisa a l’armonia sonora de la lira del ciel più l’alme invoglio. Singing to a golden lyre, I am sometimes wont to entice mortal ears, and thus, with the resounding harmonies of heaven’s lyre, I inspire the soul. Quinci à dirvi d’Orfeo desio mi sprona d’Orfeo che trasse al suo cantar le fere, e servo fè l’inferno à sue preghiere, gloria immortal di Pindo e d’Elicona. And now, spurred on by the desire to tell you of Orpheus, who drew the wild beasts with his singing and made Hell submit to his pleas – the immortal glory of Pindus and of Helicon – Hor mentre i canti alterno, hor lieti, hor mesti, non si mova augellin frà queste piante, nè s’oda in queste rive onda sonante, et ogni auretta in suo camin s’arresti. While I sing now of joy, now of sorrow, let no bird now move among these trees, nor any wave be heard upon these shores, and let every breeze stop in its path. ATTO PRIMO ACT ONE PASTORE In questo lieto e fortunato giorno ch’à posto fine à gl’amorosi affanni del nostro semideo cantiam, pastori, in sì soavi accenti che sian degni d’Orfeo nostri concenti. Oggi fatta è pietosa SHEPHERD I On this happy and fortunate day which has put an end to the pains our demigod has suffered for love, let us sing, shepherds, in such sweet accents that our refrains may be worthy of Orpheus. Today has been moved to pity 16 4 5 l’alma già sì sdegnosa de la bell’Euridice. Oggi fatto è felice Orfeo nel sen di lei, per cui già tanto per queste selve ha sospirato e pianto. Dunque in sì lieto e fortunato giorno c’hà posto fine à gli amorosi affanni del nostro semideo cantiam, pastori, in sì soavi accenti che sian degni d’Orfeo nostri concenti. the soul, once so scornful, of the lovely Eurydice; today Orpheus is made happy, in the embrace of her for whom he so often sighed and wept in these woods. So on this happy and fortunate day which has put an end to the pains our demigod has suffered for love, let us sing, shepherds, in such sweet accents that our refrains may be worthy of Orpheus. CHORO NINFE, PASTORI Vieni Imeneo, deh vieni, e la tua face ardente sia quasi un sol nascente ch’apporti à questi amanti i dì sereni e lunge homai disgombre de gl’affanni e del duol gl’orrori e l’ombre. CHORUS OF NYMPHS AND SHEPHERDS Come, Hymen, oh come! and let your flaming torch be like a sun rising to bring blissful days to these lovers; sweep far from them the horrors and shadows of suffering and grief. NINFA Muse honor di Parnasso, amor del cielo, gentil conforto à sconsolato core, vostre cetre sonore squarcino d’ogni nube il fosco velo: e mentre oggi propitio al nostro Orfeo invochiam Imeneo sù ben temprate corde sià il vostro canto al nostro suon concorde. NYMPH Muses, honour of Parnassus, beloved of Heaven, gentle comfort to disconsolate hearts, let your sonorous lyres strip the gloomy veil from every cloud: and, on this propitious day for our Orpheus, while we call on Hymen on well-tempered strings, let your song be in harmony with our playing. NINFE, PASTORI Lasciate i monti, lasciate i fonti, ninfe vezzose e liete, e in questi prati a i balli usati vago il bel piè rendete. NYMPHS AND SHEPHERDS Leave the mountains, leave the springs, you glad and graceful nymphs, and on these meadows turn your pretty feet to the familiar dances. 17 6 Qui miri il sole vostre carole più vaghe assai di quelle, ond’à la Luna, la notte bruna, danzano in ciel le stelle. Let the sun here gaze on your round-dances, far more lovely than those danced to the moon in the dusky night by the stars in heaven. pegno di pura fede à me porgesti. Se tanti cori havessi quant’occh’hà il ciel eterno, e quante chiomè han questi colli amenni il verde Maggio, tutti colmi sarieno e traboccanti di quel piacer ch’oggi mi fà contento. in a pledge of pure faith! If I had as many hearts as eternal heaven has eyes, or as these hills have leaves in green May, every one would be full and overflowing with the joy that is making me happy today. Poi di bei fiori per voi s’honori di questi amanti il crine, c’hor dei martiri de i lor desiri godon beati al fine. Then with fine flowers crown the heads of these lovers, who now, far from the torments of their desires, rejoice in bliss forever. EURIDICE Io non dirò qual sia nel tuo gioir, Orfeo, la gioia mia, che non hò meco il core, ma teco stassi in compagnia d’Amore. Chiedilo dunque à lui s’intender brami quanto lieta gioisca, e quanto t’ami. EURYDICE I can’t tell you how joyful it makes me to see you rejoice, Orpheus, because my heart is no longer with me, but with you, in the company of Love. Ask him, then, if you want to know how happy it is, and how much it loves you. PASTORE Ma tu, gentil cantor, s’à tuoi lamenti già festi lagrimar queste campagne, perc’hora al suon de la famosa cetra non fai teco gioir le valli e i poggi? Sia testimon del core qualche lieta canzon che detti Amore. SHEPHERD II But you, sweet singer, if your laments once made these fields weep, why doesn’t the sound of your famous lyre now make the valleys and hills rejoice with you? Let some joyful song inspired by Love bear witness to your heart. NINFE, PASTORI Lasciate i monti… NYMPHS, SHEPHERDS Leave the mountains… Vieni Imeneo, deh vieni… Come, Hymen, oh come!… ORFEO Rosa del ciel, vita del mondo, e degna Prole di lui che l’Universo affrena, sol, che’l tutto circondi e’l tutto miri, da gli stellanti giri, dimmi: vedestù mai di me più lieto e fortunato amante? Fu ben felice il giorno, mio ben, che pria ti vidi, e più felice l’hora che per te sospirai, poi ch’al mio sospirar tu sospirasti: felicissimo il punto che la candida mano ORPHEUS Rose of heaven, life of the world and true heir of him who governs all the universe, O sun who encompasses all and sees all, from your great circling among the stars, tell me: have you ever seen a lover happier and more blessed than me? That day was truly happy, my love, when I first saw you, and happier still the hour when I sighed for you, because at my sighing, you sighed too: happiest of all was the moment when you gave me your milk-white hand PASTORE Ma s’il nostro gioir dal ciel deriva come dal ciel ciò che quà giù n’incontra, giust’è ben che devoti gl’offriam’incensi e voti. Dunqu’al tempio ciascun rivolga i passi a pregar lui ne la cui destra è il mondo, che lungamente il nostro ben conservi. SHEPHERD III But if our joy comes to us from heaven, as does everything we meet here on earth, then it is right and proper that, with devotion, we offer up incense and vows. So let each of us turn our steps to the temple to pray to him who holds the world in his right hand, that he may long preserve our wellbeing. PASTORI Alcun non sia che disperato in preda si doni al duol, ben chè tall’hor si assaglia possente sì che nostra vita inforsa. SHEPHERDS I & IV Let no-one fall prey to despair or give himself to grief, even if sometimes it assails us with such force that it threatens our lives. Che poi che nembo rio gravido il seno d’atra tempesta inorridito hà il mondo, dispiega il sol più chiaro i rai lucenti. SHEPHERDS I, II & V For when the clouds, pregnant with dark storms, have terrified the world, the sun shows his shining beams more clearly. 18 7 8 9 0 19 ! @ £ E dopo l’aspro gel del verno ignudo veste di fior la Primavera i campi. SHEPHERDS VI & VII And after the bitter cold of naked winter, Spring clothes the fields with flowers. NINFE, PASTORI Ecco Orfeo cui pur dianzi furon cibo i sospir bevanda il pianto, oggi felice è tanto che nulla è più che da bramar gli avanzi. NYMPHS, SHEPHERDS Here is Orpheus, who only a short time ago ate the bread of sighs and drank the water of tears: today is so happy that he could wish for nothing more. ATTO SECONDO ACT TWO Sinfonia ORFEO Ecco pur ch’à voi ritorno care selve e piagge amate, da quel sol fatte beate per cui sol mie nott’han giorno. ORPHEUS Here am I with you again, dear woods and beloved shores blessed by the sun which alone has changed my night into day. PASTORE Mira, ch’à se n’alletta l’ombra Orfeo de que’ faggi hor ch’infocati raggi Febo da ciel saetta. SHEPHERD I Look how those beech trees invite us into their shade, Orpheus, now that Phoebus’ fiery rays are shooting down from heaven. Sù quel’herbosa sponde posianci, e in varii modi ciascun sua voce snodi al mormorio de l’onde. SHEPHERD IV Let’s lie down on these grassy banks and each in his own way let his voice run free to the murmuring of the waves. DUE PASTORI In questo prato adorno ogni selvaggio nume sovente hà per costume di far lieto soggiorno. SHEPHERDS I & IV In this flowery meadow it has often been the custom of the woodland gods to pass happy hours. Qui Pan, Dio de’ pastori, s’udì talhor dolente rimembrar dolcemente Here Pan, God of the shepherds, was sometimes heard sadly and sweetly recalling 20 $ % suoi sventurati amori. Qui le Nappee vezzose, (schiera sempre fiorita) con le candide dita fur viste a coglier rose. his unhappy loves. Here the graceful nymphs (always garlanded with flowers) were seen to pick roses with their white hands. NINFE, PASTORI Dunque fà degno Orfeo, del suon de la tua lira questi campi ove spira aura d’odor Sabeo. NYMPHS AND SHEPHERDS So, Orpheus, dignify with the sound of your lyre these fields where breezes waft the perfumes of Arabia. ORFEO Vi ricorda ò boschi ombrosi, de’ miei lunghi aspri tormenti, quando i sassi ai miei lamenti rispondean fatti pietosi? ORPHEUS Do you remember, O shady woods, my long and bitter torments, when the stones, moved to pity, responded to my laments? Dite, allhor non vi sembrai più d’ogni altro sconsolato? Hor fortuna hà stil cangiato et hà volto in festa i guai. Tell me, did I not then seem to you more wretched than anyone? Now Fate has changed her tune and turned my griefs into revels. Vissi già mesto e dolente, hor gioisco e quegli affanni che sofferti hò per tant’anni fan più caro il ben presente. My life then was sad and sorrowful, but now I rejoice, and those miseries I suffered for so many years make my present good fortune all the more dear. Sol per te, bella Euridice, benedico il mio tormento. Dopò’l duol vi è più contento, dopò’l mal vi è più felice. Only because of you, fair Eurydice, do I bless those torments; after pain, one is the more contented, after misfortune, one is the happier. PASTORE Mira, deh mira, Orfeo, che d’ogni intorno ride il bosco e ride il prato. Segui pur col plettr’aurato d’addolcir l’aria sì beato giorno. SHEPHERD I Come, look now, Orpheus, how all around you the woods and the fields are laughing! Continue then with your golden plectrum, to sweeten the air of this blessed day. 21 MESSAGGIERA Ahi, caso acerbo! Ahi, fat’empio e crudele! Ahi, stelle ingiuriose! Ahi, ciel avaro! MESSENGER Ah, bitter chance! Ah, evil and cruel fate! Ah, malignant stars! Ah, greedy heavens! PASTORE Qual suon dolente il lieto dì perturba? SHEPHERD I What mournful sound disturbs this happy day? MESSAGGIERA Lassa, dunque, debb’io, mentre Orfeo con sue note il ciel consola con le parole mie passargli il core? MESSENGER Alas, must I then, while Orpheus charms the heavens with his music, pierce his heart with my words? PASTORE Questa è Silvia gentile, dolcissima compagna della bell’Euridice: ò quanto è in vista dolorosa! Hor che fia? Deh sommi dei, non torcete da noi benigno il guardo. SHEPHERD VIII This is the gentle Sylvia, sweetest companion of the fair Eurydice; Oh, how sad she looks! What is happening? Ah, great gods, don’t turn your kindly gaze away from us! MESSAGGIERA Pastor lasciate il canto, ch’ogni nostra allegrezza in doglia è volta. MESSENGER Shepherds, leave off your singing, for today all our joy is turned to grief. ORFEO D’onde vieni? Ove vai? Ninfa che porti? ORPHEUS Where have you come from? Where are you going? Nymph, what is it you bring? MESSAGGIERA A te ne vengo Orfeo messagiera infelice di caso più infelice e più funesto. La tua bella Euridice... MESSENGER I come to you, Orpheus bearing sad tidings of the saddest and most grievous ill-fortune. Your beautiful Eurydice... ORFEO Ohimè che odo? ORPHEUS Alas, what am I hearing? MESSAGGIERA La tua diletta sposa è morta. MESSENGER Your beloved bride is dead! 22 ^ ORFEO Ohimè. ORPHEUS Alas! MESSAGGIERA In un fiorito prato con l’altre sue compagne, giva cogliendo fiori per farne una ghirlanda à le sue chiome, quand’angue insidioso, ch’era fra l’erbe ascoso, le punse un piè con velenoso dente. Ed ecco immantinente scolorissi il bel viso e ne’ suoi lumi sparir que’lampi, ond’ella al sol fea scorno. Allhor noi tutte sbigottite e meste le fummo intorno richiamar tentando gli spirti in lei smarriti con l’onda fresca e co’possenti carmi. Ma nulla valse, ahi lassa, ch’ella i languidi lumi alquanto aprendo, e te chiamando Orfeo, dopò un grave sospiro, spirò fra queste braccia, ed io rimasi pieno il cor di pietade e di spavento. MESSENGER In a flowery field with her companions she was walking around gathering flowers to make a garland for her hair, when a treacherous serpent hidden in the grass pierced her foot with its poison fang. And behold, straight away her lovely face grew pale, and in her eyes, the light that once put the sun to shame grew dim. Then we, all horrified and sad, gathered around her, trying to call back her failing spirit with cool water and powerful charms: but all was in vain, alas! For, half-opening her heavy eyes, and calling to you, Orpheus, after a deep sigh she died in these arms, and I was left with my heart full of pity and fear. PASTORE Ahi, caso acerbo!… SHEPHERD I Ah, bitter chance!… SECONDO PASTORE A l’amara novella rassembra l’infelice un muto sasso che per troppo dolor non può dolersi. SHEPHERD IV At this bitter news the poor man seems a mute stone, his grief so great that he cannot grieve. Ahi, ben havrebbe un cor di tigre o d’orsa chi non sentisse del tuo mal pietade, privo d’ogni tuo ben, misero amante. SHEPHERD I Ah, surely he would have the heart of a tiger or a bear who felt no pity for your pain, bereft of your beloved, O wretched lover! 23 & * ( ORFEO Tu se’ morta, mia vita, ed io respiro? tu se’ da me partita per mai più non tornare, ed io rimango? Nò, che se i versi alcuna cosa ponno, n’andrò sicuro a più profondi abissi e intenerito il cor del Rè de l’Ombre, meco trarròtti a riveder le stelle. O se ciò negheràmmi empio destino, rimarrò teco in compagnia di morte, A dio terra, à dio cielo, e sole, à dio. ORPHEUS You are dead, my life, and am I still breathing? You have gone from me, shall never return to me, and I am still here? No, for if my verses can do anything, I shall surely go down to the deepest abysses and melt the heart of the King of Shadows, bringing you back with me to see the stars once again. Or, if evil fate denies me this, I shall stay with you in the company of death: Farewell to earth, to sky, to sun, farewell. NINFE, PASTORI Ahi, caso acerbo!… NYMPHS, SHEPHERDS Ah, bitter chance!… Non si fidi huom mortale di ben caduco e frale che tosto fugge, e spesso a gran salita il precipizio è presso. Mortal man, do not put your trust in fleeting, fragile happiness which soon is fled, and often the highest leap lands on the precipice. MESSAGGIERA Ma io ch’in questa lingua hò portato il coltello c’hà svenata ad Orfeo l’anima amante, odiosa à i Pastori et à le Ninfe, odiosa à me stessa, ove m’ascondo? Nottola infausta il sole fuggirò sempre e in solitario speco menerò vita al mio dolor conforme. MESSENGER But I, whose tongue carried the knife that bled dry the loving soul of Orpheus: hateful to the shepherds and to the nymphs, hateful to my very self, where shall I hide? An ill-omened bat, I shall forever flee the sun and in some solitary cave lead a life befitting my grief. PASTORI Chi ne consola, ahi lassi? O pur chi ne concede negl’occhi un vivo fonte da poter lagrimar come conviensi in questo mesto giorno, quanto più lieto gia tant’hor più mesto? SHEPHERDS I & VII Who will console us, alas? Or rather, who will lend to our eyes a living spring, that we may weep as is fitting on this sad day, all the sadder for having been so glad? 24 ) 1 2 Oggi turbo crudele i due lumi maggiori di queste nostre selve, Euridice e Orfeo, l’una punta da l’angue, l’altro dal duol trafitto, ahi lassi, ha spenti. Today, a cruel twist of fate has put out the two greatest lights of these our woods, Eurydice and Orpheus, the one stung by a serpent, the other, alas, transfixed with grief. NINFE, PASTORI Ahi, caso acerbo!… NYMPHS, SHEPHERDS Ah, bitter chance!… PASTORI Ma dove, ah dove hor sono de la misera Ninfa le belle e fredde membra, dove suo degno albergo quella bell’alma elesse ch’oggi è partita in su’l fiorir de’ giorni? Andiam Pastori, andiamo pietosi à ritrovarle, e di lagrime amare il dovuto tributo per noi si paghi almeno al corpo esangue. SHEPHERDS I & VII But where, ah, where now are the beautiful, cold limbs of the wretched nymph, where the worthy dwelling-place chosen by that sweet soul which today has departed in the flower of youth? Come, shepherds, let us go in pity to find her and in bitter tears let us pay due honour at least to her bloodless body. PASTORI Ahi, caso acerbo!… SHEPHERDS Ah, bitter chance!… CD2 ATTO TERZO ACT THREE Sinfonia ORFEO Scorto da te mio Nume Speranza, unico bene de gl’afflitti mortali, omai son giunto a questi mesti et tenebrosi regni ove raggio di sol giamai non giunse. Tù mia compagna e duce ORPHEUS Escorted by you, my Goddess, Hope, only solace of afflicted mortals, at last I have arrived in these sad and shadowy lands where no ray of sunlight has ever reached. You, my companion and guide, 25 3 4 in così strane e sconosciute vie regesti il passo debole e tremante, ond’oggi ancora spero di riveder quelle beate luci che sol’à gl’occhi miei portan’ il giorno. along such strange and unknown paths have supported my weak and trembling steps, where today I hope once more to see again those beautiful eyes which alone can bring daylight to my own. SPERANZA Ecco l’atra palude, ecco il nocchiero che trahe l’ignudi spirti a l’altra riva dove hà Pluton de l’ombre il vasto impero. Oltre quel nero stagn’, oltre quel fiume, in quei campi di pianto e di dolori, Destin crudele ogni tuo ben t’asconde. Hor d’uopo è d’un gran core e d’un bel canto. Io fin qui t’hò condotto, hor più non lice teco venir, ch’amara legge il vieta. Legge scritta co’l ferro in duro sasso de l’ima reggia in sù l’orribil soglia ch’in queste note il fiero senso esprime, Lasciate ogni speranza ò voi ch’entrate. Dunque, se stabilito hai pur nel core di porre il piè nella città dolente, da te me’n fuggo e torno a l’usato soggiorno. HOPE Here is the dark marsh, here is the helmsman who ferries naked souls to the far shore where Pluto rules his vast empire of shadows. Beyond that black swamp, beyond that river, in those fields of weeping and of pain, cruel Fate is hiding your beloved from you. Now there is need of courage and of sweet singing. I have led you this far, but I may not come any further with you; harsh law forbids it, a law engraved with iron in hard stone over the dreadful threshold of the deepest realm, which expresses its cruel message in these words: ‘Abandon all hope, ye who enter here!’ Therefore, if you are resolved in your heart to set foot in this city of pain, I must flee from you and return to familiar surrounds. ORFEO Dove, ah dove te’n vai, unico del mio cor dolce conforto? Poi che non lunge homai del mio lungo camin si scopr’il porto, perche ti parti e m’abbandoni, ahi lasso, sul periglioso passo? Qual bene hor più m’avanza se fuggi tù, dolcissima Speranza? ORPHEUS Where, ah where are you going, only sweet comfort of my heart? Since not far away now I see the gate that ends my long journey, why do you depart and leave me alone, alas, at this perilous threshold? What good remains for me now if you, dearest Hope, are fled? CARONTE O tu ch’innanzi mort’a queste rive temerario te’n vieni, arresta i passi. CHARON O you who, not yet dead, are come recklessly to this shore, come no farther. 26 5 6 7 Solcar quest’onde ad huom mortal non dassi, nè può co’ morti albergo haver chi vive. Che? Voi forse, nemico al mio Signore, Cerbero trar da le tartaree porte? O rapir brami sua cara consorte d’impudico desire acceso il core? Pon freno al folle ardir, ch’entr’al mio legno non accorrò più mai corporea salma, sì de gli antichi oltraggi ancor ne l’alma serbo acerba memoria e giusto sdegno. It is not given to mortal man to plough these waves, nor may the living find shelter with the dead. What? Perhaps, an enemy of my master, you seek to drag Cerberus from the doors of Tartarus? Or do you want to ravish his beloved consort, your heart consumed with indecent desires? Put a stop to your foolhardiness, for no living body shall I ever allow to enter my boat, for the ancient affronts still awaken in my soul bitter memories and just resentment. ORFEO Possente Spirto e formidabil nume, senza cui far passaggio à l’altra riva alma da corpo sciolta in van presume: ORPHEUS Mighty Spirit, awe-inspiring God, without whom no bodiless soul can presume to cross to the far shore: Non vivo io nò, che poi di vita è priva mia cara sposa, il cor non è più meco, e senza cor com’esser può ch’io viva? I am not alive, for my beloved bride is deprived of life, my heart is no longer with me, and with no heart, how can I be alive? A lei volt’hò il camin per l’aër cieco, a l’inferno non già, ch’ovunque stassi tanta bellezza il paradiso hà seco. I have made my way to her through the blind air, yet not to Hell, for wherever dwells such beauty, there is Paradise. Orfeo son io che d’Euridice i passi seguo per queste tenebrose arene, ove già mai per huom mortal non vassi. O de le luci mie luci serene, s’un vostro sguardo può tornarmi in vita, Ahi, chi niega il conforto à le mie pene? Sol tu, nobile Dio, puoi darmi aita, nè temer dei, che sopr’un’aurea cetra sol di corde soavi armo il dita contra cui rigid’alma in van s’impetra. I am Orpheus, following Eurydice’s steps through these shadowy lands, where no mortal man has ever trod. O clear light of my eyes, if one glance from you can restore me to life, ah, who would deny me comfort in my pain? You alone, noble God, can help me, nor should you be afraid, for on a golden lyre my fingers are armed only with sweet strings against which the obdurate soul hardens itself in vain. CARONTE Ben mi lusinga alquanto dilettandomi il core, CHARON I am indeed rather charmed, my heart delighted, 27 sconsolato cantore, il tuo piant’el tuo canto. Ma lunge, ah lunge sia da questo petto pietà, di mio valor non degno affetto. O unhappy singer, by your lament and your song. But far, ah, far from this breast be pity, a sentiment unworthy of my dignity. ORFEO Ahi, sventurato amante! Sperar dunque non lice ch’odan miei prieghi i cittadin d’Averno? Onde qual’ ombra errante d’insepolto cadavero infelice, privo sarò del cielo e de l’inferno? Così vuol empia sorte ch’in questi orror di morte da te cor mio lontano, chiami tuo nome in vano, e pregando e piangendo io mi consumi? Rendetemi il mio ben, Tartarei Numi. ORPHEUS Alas for me, unhappy lover! Then may I not hope that the people of Avernus may hear my pleas? Like the wandering shade of an unburied, hapless corpse, shall I be denied both heaven and hell? Does evil Fate wish it thus, that in this horror of death, far from you, my dear heart, I shall call your name in vain, and waste away with begging and weeping? Give me back my love, Gods of Tartarus! Ei de l’instabil piano arò gl’ondosi campi, e’l seme sparse di sue fatiche, ond’aurea messe accolse. Quinci perchè memoria vivesse di sua gloria, La fama à dir di lui sua lingua sciolse, chei pose freno al mar con fragil legno, che sprezzò d’Austr’e d’Aquilon lo sdegno. 0 Sinfonia 8 Ei dorme, e la mia cetra se pietà non impetra ne l’indurato core, almen il sonno fuggir al mio cantar gli occhi non ponno. Sù dunque, a che più tardo? Temp’è ben d’approdar su l’altra sponda, s’alcun non è ch’il nieghi, Vaglia l’ardir se foran van’i preghi. È vago fior del tempo l’occasion, ch’esser dee colta à tempo. Mentre versan quest’occhi amari fiumi rendetemi il mio ben, Tartarei Numi. 9 Sinfonia a 7 He sleeps, and though my lyre could wring no pity from that hardened heart, at least his eyes could not escape from slumber at my singing. So then, why wait any longer? It is high time I head for the far shore, if there is no-one to hinder me, let courage prevail, since prayers were in vain. Opportunity is a delicate flower of time which must be plucked at the right moment. While bitter streams flow from these eyes, give me back my love, Gods of Tartarus! ! SPIRITI INFERNALI Nulla impresa per huom si tenta in vano, nè contro lui più sà natura armarse. SPIRITS OF HELL Nothing attempted by man is in vain, nor has nature any defences against him. 28 He has tilled the rolling fields of the shifting plains, and scattered the seeds of his labour, reaping a golden harvest. And so, to keep the memory of his glory alive, Fame has loosed her tongue to speak of him who has tamed the sea in a fragile bark, mocking the fury of the South and North Winds. ATTO QUARTO ACT FOUR PROSERPINA Signor, quel infelice che per queste di morte ampie campagne và chiamand’Euridice, ch’udit’hai tù pur dianzi così soavemente lamentarsi, moss’hà tanta pietà dentr’al mio core ch’un’altra volta io torno a porger preghi perchè il tuo Nume al suo pregar si pieghi. Deh, se da queste luci amorosa dolcezza unqua trahesti se ti piacqu’il seren di questa fronte che tù chiami tuo cielo, onde mi giuri, di non invidiar sua sorte à Giove, pregoti, per quel foco, con cui già la grand’alma Amor t’accese, fa ch’Euridice torni a goder di quei giorni che trar solea vivend’in feste e in canto, e del miser Orfeo consola’l pianto. PERSEPHONE My Lord, that wretched man who wanders these vast fields of the dead calling for Eurydice, whom you have just heard lamenting so sweetly, has stirred such pity in my heart that once again I come to appeal to Your Divinity to hear his prayers. Oh, if from these eyes you have ever drawn the sweetness of love, if ever you have taken delight in this calm brow which you call your heaven, by which you swore to me never to envy the fate of Jove, I implore you, by that very fire with which Love set your great soul aflame, let Eurydice return to enjoy those days that she used to spend in feasting and song, and console the tears of the wretched Orpheus. PLUTONE Benchè severo ed immutabil fato contrasti, amata sposa, a i tuoi desiri, pur null’homai si nieghi a tal beltà congiunta a tanti prieghi. PLUTO Though a stern and unyielding fate opposes your wishes, beloved bride, let nothing be denied to such beauty allied with so many prayers. 29 La sua cara Euridice contra l’ordin fatale Orfeo ricovri. Ma pria che trag’il piè da questi abissi non mai volga ver lei gli avidi lumi, che di perdita eterna gli sia certa cagion un solo sguardo. Io così stabilisco. Hor nel mio Regno fate o Ministri il mio voler palese, sì che l’intenda Orfeo e l’intenda Euridice ne di cangiar l’altrui sperar più lice. His beloved Eurydice shall be returned to Orpheus, against fate’s decree. But while he yet treads these abysses he shall not turn his eager eyes to her, for eternal loss shall certainly result from even a single glance. Thus I ordain. Now, ministers, make my will known throughout my kingdom, so that Orpheus understands it and Eurydice understands it and let no-one hope to change it. SPIRITI INFERNALI O degli habitator de l’ombre eterne possente Rè legge ne sia tuo cenno, che ricercar altre cagioni interne di tuo voler nostri pensier non denno. SPIRIT I O mighty King of all inhabitants of eternal darkness, you nod your head and it is law, for it is not given to us to seek the deeper workings of your will. Trarrà da quest’orribili caverne sua sposa Orfeo, s’adoprerà suo ingegno si che no’l vinca giovenil desio, ne i gravi imperi suoi sparga d’oblio. SPIRIT II Will Orpheus carry his bride from these dread caverns, will he employ his intelligence to resist youthful desire and to remain mindful of the stern commands? PROSERPINA Quali grazie ti rendo hor che sì nobil dono conced’a preghi miei, Signor cortese? Sia benedetto il dì che pria ti piacqui, benedetta la preda e’l dolc’inganno, poi chè per mia ventura feci acquisto di tè perdendo sole. PERSEPHONE What thanks can I give you now that you have granted such a noble gift to my prayers, my gentle Lord? Blessed be the day I first pleased you, blessed the abduction and the sweet deception, since it was my good fortune, losing the sun, to gain you. PLUTONE Tue soavi parole d’amor l’antica piaga PLUTO Your sweet words re-open the old wound of love $ % @ £ 30 rinfrescan nel mio core; così l’anima tua non sia più vaga di celeste diletto, si ch’abbandoni il marital tuo letto. in my heart; so let your soul no longer be distracted by heavenly delights that cause you to forsake your marriage bed. SPIRITI INFERNALI Pietade oggi et Amore trionfan ne l’inferno. SPIRITS OF HELL Today Pity and Love have triumphed in Hell. Ecco il gentil cantore, che sua sposa conduce al ciel superno. SPIRIT I Here is the noble singer, leading his bride to heavenly heights. Ritornello ORFEO Qual honor di te fia degno, mia cetra onnipotente, s’hai nel Tartareo regno piegar potuto ogni indurata mente? Luogo havrai fra le più belle imagini celesti ond’al tuo suon le stelle danzeranno co’gir’hor tard’hor presti. ORPHEUS What honour could do you justice, my all-powerful lyre, since you have been able to bend every obdurate mind in the kingdom of Tartarus? You shall have a place among the fairest images of heaven, where at your sound the stars will dance in rounds, now slow, now fast. Io per te felice à pieno vedrò l’amato volto, e nel candido seno de la mia donn’oggi sarò raccolto. Filled with happiness, thanks to you, I shall see the beloved face and be gathered today into the white breast of my lady. Ma mentre io canto ohimè chi m’assicura ch’ella mi segua? Ohimè chi mi nasconde de le amate pupille il dolce lume? Forse d’invidia punte le Deità d’Averno perch’io non sia qua giù felice à pieno mi tolgono il mirarvi luci beate e liete, che sol col sguardo altrui bear potete? But while I sing, alas, how can I know for sure that she is following? Alas, who is concealing from me the sweet light of her beloved eyes? Perhaps, stung by jealousy, the Gods of Avernus, to prevent me from finding such happiness here below, are depriving me of the sight of you, O blessed, happy eyes which with a single glance have the power to bring bliss? 31 ^ Ma che temi, mio core? Ciò che vieta Pluton comanda Amore. A nume più possente, che vince huomini e dei, ben ubidir dovrei. (Quì si fa strepito dietro alla Scena) Ma che odo, ohimè lasso? S’arman forse à miei danni con tal furor le Furie innamorate per rapirmi il mio ben, ed io’l consento? (qui si volta) O dolcissimi lumi, io pur vi veggio, io pur... ma qual eclissi ohimè v’oscura? But what do you fear, my heart? What Pluto has forbidden, Love commands. I must obey a mightier god, who rules over both gods and men. (A noise is heard off-stage) But what do I hear, ah me? Can it be that the love-crazed Furies are arming themselves in a frenzy to do me injury, to rob me of my love, and I am letting it happen? (He turns) O sweetest eyes, now I see you now, now I...But alas, what eclipse wraps you in darkness? UNO SPIRITO Rott’hai la legge, e se’ di grazia indegno. SPIRIT II You have broken the law, and are unworthy of mercy. EURIDICE Ahi, vista troppo dolce e troppo amara; Così per troppo amor dunque mi perdi? Et io misera perdo il poter più godere e di luce e di vista, e perdo insieme tè d’ogni ben più caro, mio consorte. EURYDICE Ah, vision too sweet and too bitter! Thus, for having loved too much, you lose me now? And I, wretched woman, lose the power to ever again enjoy either light or sight, and with that I lose you, dearest of all treasures, my spouse. UNO SPIRITO Torn’a l’ombre di morte infelice Euridice, nè più sperar di riveder le stelle ch’omai fia sordo à preghi tuoi l’inferno. SPIRIT I Turn back to the shadows of death, unhappy Eurydice, and do not hope to see the stars again, for now all Hell will be deaf to your prayers. ORFEO Dove te’n vai, mia vita? Ecco io ti seguo. Ma chi me’l nieg’, ohimè: sogn’, o vaneggio? Qual occulto poter, di questi orrori, da questi amati orrori ORPHEUS Where are you going, my life? Look, I will follow you. But who is holding me back, alas: am I dreaming, or raving? What occult power among these horrors, these beloved horrors, 32 mal mio grado mi tragge, e mi conduce a l’odiosa luce? & * drags me away against my will, and leads me to the loathsome light? Sinfonia a 7 SPIRITI INFERNALI È la virtute un raggio di celeste bellezza, preggio de l’alma ond’ella sol s’apprezza: Questa di temp’oltraggio non tem’, anzi maggiore nell’huom rendono gl’anni il suo splendore. Orfeo vinse l’inferno e vinto poi fù da gl’affetti suoi. Degno d’eterna gloria fia sol colui c’havrà di se vittoria. SPIRITS OF HELL Virtue is a ray of celestial beauty, prize of the soul, which alone knows its worth: She has no fear of the ravages of time, rather, in man the years render her splendour all the greater. Orpheus conquered Hell and then was defeated by his own emotions. Only the man who conquers himself is worthy of eternal glory. ATTO QUINTO ACT FIVE Ritornello ORFEO Questi i campi di Tracia, e quest’è il loco dove passomm’il core per l’amara novella il mio dolore. Poiche non hò più spene di ricovrar pregando piangendo e sospirando il perduto mio bene, che poss’io più? se non volgermi à voi, selve soavi, un tempo conforto a’ miei martir, mentr’al ciel piacque, per farvi per pietà meco languire al mio languire. Voi vi doleste, o monti, e lagrimaste voi, sassi, al dipartir del nostro sole, et io con voi lagrimerò mai sempre, e mai sempre dorròmmi, ahi doglia, ahi pianto. ORPHEUS These are the gardens of Thrace, and this the place where my heart was pierced with the bitter news of my sorrow. Now that I no longer have any hope that my prayers, my tears and my sighs might recover the treasure I have lost, what can I do but turn to you, sweet woods, who once brought comfort to my suffering, when heaven was pleased to make you languish with me for pity of my languishing? You grieved, O mountains, and you wept, stones, when our sun departed, and I shall now weep with you for ever and forever give myself over to sorrow, ah grief, ah tears. 33 ( ECO Hai pianto. ECHO Your tears! ORFEO Cortese Eco amorosa che sconsolata sei, e consolarmi voi ne’ dolor miei, benchè queste mie luci sien già per lagrimar fatte due fonti, in così grave mia fera sventura non ho pianto però tanto che basti. ORPHEUS Gentle, loving Echo, disconsolate yourself, you seek to console me in my suffering; though these eyes of mine have already through weeping become two springs, in this my heavy, harsh misfortune I have not tears enough. ECO Basti. ECHO Enough. ORFEO Se gl’occhi d’Arg’avessi, e spandessero tutti un mar di pianto, non forà il duol conforme à tanti guai. ORPHEUS If I had the eyes of Argus and could pour out a sea of tears, the sorrow would not match such woe. ECO Ahi. ECHO Oh! ORFEO S’hai del mio mal pietade, io ti ringrazio di tua benignitade. Ma mentr’io mi querelo deh, perchè mi rispondi sol con gl’ultim’accenti? Rendimi tutt’integri i miei lamenti. ORPHEUS If you pity my plight, I thank you for your kindness. But while I am making accusations, oh, why do you answer me only with the last word? Give me back my laments in full. Ma tu anima mia se mai ritorna la tua fredd’ombra à quest’amiche piaggie, prendi da me queste tue lodi estreme, c’hor à te sacro la mia cetra e’l canto. Come à te già sopra l’altar del core lo spirto acceso in sacrifizio offersi. Tu bella fusti e saggia, e in te ripose tutte le grazie sue cortese il cielo, But you, my soul, if ever your cold shade returns to these friendly slopes, accept from me these last praises which I dedicate to you now, my lyre and my song, just as once on the altar of the heart I offered my burning spirit to you in sacrifice. You were beautiful and wise, and on you heaven poured all its kind graces, 34 ) mentre ad ogn’altra de suoi don fù scarso, d’ogni lingua ogni lode à te conviensi ch’albergasti in bel corpo alma più bella, fastosa men quanto d’honor più degna. Hor l’altre donne son superbe e perfide ver chi le adora, dispietate instabili, prive di senno e d’ogni pensier nobile, ond’à ragion opra di lor non lodansi, quinci non fia giamai che per vil femina Amor con aureo stral’ il cor trafiggami. yet was miserly in its gifts to all other women; you are worthy of all praise from all tongues for your lovely body sheltered an even lovelier soul, all the more worthy of honour for lacking ostentation. Now other women are proud and deceitful, pitiless and fickle towards those who love them; they lack good sense and noble thoughts, hence it is right that they should receive no praise, so let it never be that for a worthless woman Love’s golden arrow should transfix my heart. APOLLO Perch’a lo sdegno et al dolor in preda cosi ti doni, ò figlio? Non è, non è consiglio di generoso petto servir al proprio affetto. Quinci biasmo e periglio già sovrastar ti veggio onde movo dal ciel per darti aita: hor tu m’ascolta e n’havrai lode e vita. APOLLO Why do you give yourself over to scorn and grief like this, my son? It is not wise, not wise for a generous heart to be a slave to its own passions. Since I see blame and peril already overcoming you, I have come from heaven to bring you help: listen to me, and you shall have praise and life. ORFEO Padre cortese, al maggior uopo arrivi, ch’a disperato fine con estremo dolore m’havean condotto già sdegn’e amore. Eccomi dunque attento a tue ragioni, celeste padre; hor ciò che vuoi m’imponi. ORPHEUS Kind father, you have come in my hour of greatest need, for already, with the uttermost grief, scorn and love were leading me to desperate ends. See how I am attentive to your words of reason, heavenly father; now impose on me what you will. APOLLO Troppo, troppo gioisti di tua lieta ventura, hor troppo piagni tua sorte acerba e dura. Ancor non sai APOLLO Too much, too much you rejoiced in your glad fortune; now too much you bemoan your hard and bitter fate. Have you not yet learned 35 Come nulla qua giù diletta e dura? Dunque se goder brami immortal vita Vientene meco al ciel ch’a sè t’invita. how nothing delightful here below will last for long? So if you want to enjoy immortal life, come with me to heaven, which welcomes you. Cantillation Antony Walker, Music Director Alison Johnston, Manager Orchestra of the Antipodes Antony Walker, Music Director Alison Johnston, Manager ORFEO Si non vedrò più mai de l’amata Euridice i dolci rai? ORPHEUS Shall I never again see the sweet eyes of my beloved Eurydice? Violin Sophie Gent APOLLO Nel sole e nelle stelle vagheggerai le sue sembianze belle. APOLLO In the sun and the stars you will be able to admire her fair likeness. Sopranos Anna Fraser Belinda Montgomery Alison Morgan Josie Ryan Jane Sheldon ORFEO Ben di cotanto padre sarei non degno figlio, se non seguissi il tuo fedel consiglio. ¡ ™ ORPHEUS Of such a father I would not be a worthy son if I did not follow your faithful counsel. APOLLO, ORFEO Saliam cantand’al cielo, dove ha virtù verace degno premio di sè, diletto e pace APOLLO, ORPHEUS Let us ascend singing to heaven, where true virtue has its just reward, delight and peace. CORO DI SPIRITI Vanne, Orfeo, felice a pieno a goder celeste honore, la ve ben non mai vien meno, la ve mai non fu dolore, mentr’altari incensi e voti noi t’offriam lieti e devoti. CHORUS OF SPIRITS Go now, Orpheus, filled with happiness, to enjoy celestial honours; where good never fails, where there has never been any sorrow, while we offer you altars, incense and vows in gladness and devotion. Così va chi non s’arretra al chiamar di nume eterno, così grazia in ciel impetra chi qua giù provò l’inferno, e chi semina fra doglie d’ogni grazia il frutto coglie. # So it is for the one who does not hesitate at the call of the eternal god, thus the one who has tasted hell here below is filled with grace in heaven, and the one who sows in tears reaps the fruits of all grace. Moresca Altos Jenny Duck-Chong Anne Farrell Natalie Shea Arthur Robinson, Perth, Australia, 1998, after Amati Elizabeth Pogson Anonymous, after Sebastian Klotz Viola Nicole Forsyth Tenor viola by Ian Clarke, Biddeston, Australia, 1998, after Giovanni Paolo Maggini, ‘Dumas’, c.1680 Tenors Philip Chu Benjamin Loomes Daniel Walker Brett Weymark Raff Wilson Viola da gamba Daniel Yeadon Basses Daniel Beer Corin Bone Craig Everingham David Greco G & M Lyndon-Jones, St Albans, UK, 1992, after various originals Cornetto Danny Lucin Serge Dalmas, Paris, France, 2002, after various originals Gregory Rogers Serge Dalmas, Paris, France, 1998, after various 17th-century originals Sackbut Scott Kinmont Alto sackbut by John Webb, Wiltshire, UK, 1995, after various Italian instruments Warwick Tyrrell Petr Vavrous, Prague, Czech Republic, 2002, after Bertrand, c.1720 Alto and tenor sackbuts by John Webb, Wiltshire, UK, 1995, after various Italian instruments Anthea Cottee Robert Collins Gary D. Bridgewood, London, UK, 1987; bow by Juta Walsher, Oxford, 1996 Tenor sackbut by Frank Tomes, England, 1991, after Georg Neuschel, 1557 Violone Kirsty McCahon Nigel Crocker Anonymous copy after Maggini, 17th century. Used courtesy of Winsome Evans and the Department of Music, University of Sydney Recorder Matthew Ridley Melissa Farrow Renaissance recorders by Michael Grinter, Victoria, Australia; Peter Kobliczek, Germany; David Coomber, Auckland, New Zealand; and Paul Whinray, Auckland, New Zealand, after 16th-century originals Translation: Natalie Shea 36 Curtal Simon Rickard 37 Tenor sackbut by John Webb, Wiltshire, UK, 1995, after various Italian instruments Glenn Bardwell Tenor sackbut by Rainer Egger, Switzerland, 2000, after Sebastian Hainlein, 1632 Bass Sackbut in F by Frank Tomes, England, 1992 after Issac Ehe, 1612 Baroque Harp Marshall McGuire Italian double harp by Tim Hobrough, Scotland, 1989, after Trabaci, c.1600 Harpsichord Erin Helyard ‘Strato’, William Bright, near Barraba, Australia, 2002, after Johannes Ruckers, 1624, 1638 and 1640; lid painting by Rupert Richardson. Used courtesy of the Powerhouse Museum, Sydney Neal Peres da Costa ‘Baron’, William Bright, near Barraba, Australia, 1998, after Johannes Ruckers, 1624, 1638 and 1640; lid painting by Rupert Richardson. Used courtesy of the Australian Chamber Orchestra Chamber organ Erin Helyard Bernhard Fleig, Switzerland, 1996. Used courtesy of Sydney Grammar School Samantha Cohen Theorbo by Klaus Jacobsen, London, 1999 Baroque guitar by Lars Jonsson, Dalarö, Sweden, 1999 Percussion Richard Gleeson Instruments include calfskin-head Premier tenor and bass drums; calfskinhead Lefima field drum with gut snares; calfskin-head Lefima davul and tambourine; fishskin-head maple Cooperman Riq jingled drum; tamburello; Turkish cymbal Tuning: A440 Temperament: 1/4 comma meantone of 1523 Lute/Theorbo/Guitar Deborah Fox Baroque guitar by Jaume Bosser, Barcelona, Spain, 1999, after various 17th-century Italian makers Theorbo by Michael Schreiner, Toronto, Canada, 2000, after Kaiser, Italy, 1611 Tommie Andersson Lute by Richard Earle, Basel, Switzerland, 1983, after Venere, Padua, Italy 1582 Theorbo by Peter Biffin, Armidale, Australia, 1995, after various 17thcentury Italian makers Baroque guitar by Peter Biffin, Armidale, Australia, 1989, after Stradivarius, Cremona, Italy, 1680 Chitarrino by Alexander Hopkins, Mallorca, Spain, 2004 after Dias, 1586 Executive Producers Robert Patterson, Lyle Chan Recording Producer, Editor and Mastering Virginia Read Recording Engineers Christian Huff-Johnston, Virginia Read Project Coordinator Alison Johnston Editorial and Production Manager Natalie Shea Cover and Booklet Design Imagecorp Pty Ltd Cover Image Jean Cocteau Orphée à la lyre © 1960, used with kind permission of the Comité Jean Cocteau Back Cover Map Image Johannes Van Keulen, Oost Indien (detail), c.1689 Portrait of Claudio Monteverdi Bernardo Strozzi, used with kind permission of Tiroler Landesmuseum Ferdinandeum, Innsbruck Photography Gerald Jenkins (Mark Tucker), Steven Godbee (Paul McMahon), Michael Chetham (Belinda Montgomery), Simon Hodgson (Antony Walker, Penelope Mills, Anna Fraser and all production photographs), Ed Hughes (all others). 2005 Australian Broadcasting Corporation. © 2005 Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Distributed in Australia by Universal Music Group, under exclusive licence. Made in Australia. All rights of the owner of copyright reserved. Any copying, renting, lending, diffusion, public performance or broadcast of this record without the authority of the copyright owner is prohibited. For Pinchgut Opera’s production of L’Orfeo Director Mark Gaal Repetiteurs Erin Helyard and Deborah Fox Designers Mark Gaal and Alice Lau Lighting Designer Bernie Tan Production Manager Andrew Johnston Assistant Conductor Erin Helyard Stage Manager Sarah Smith Design Associate Brendan Blakely Costume Supervisor Tirion Rodwell Assistant Director Tanya Goldberg Language Coach Nicole Dorigo Harpsichord tuning and maintenance Terry Harper Chamber organ tuning and maintenance Manuel S. Da Costa For Pinchgut Opera Artistic Directors Erin Helyard and Antony Walker Artistic Administrator Alison Johnston Marketing Manager Anna Cerneaz Chair Elizabeth Nielsen Recorded live 1, 3, 5 and 6 December 2004 at City Recital Hall, Angel Place, Sydney. www.pinchgutopera.com.au 38 39