Malvina Matthews - Mississippi Department of Archives and History

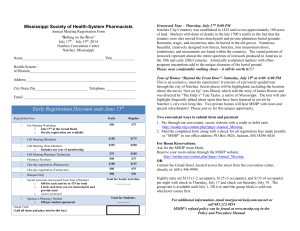

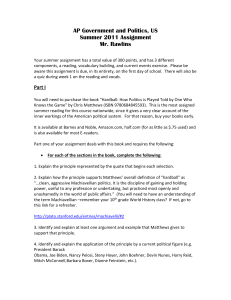

advertisement