John R. Commons and the Foundations of

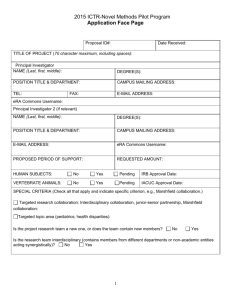

advertisement