The Contagion of Nonviolent Conflict Between Autocracies

advertisement

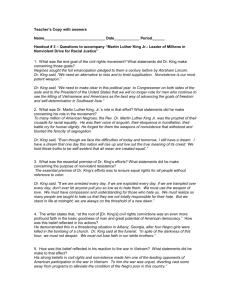

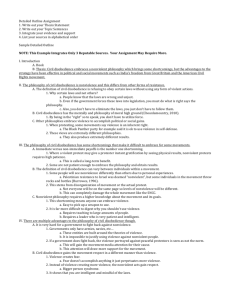

The Contagion of Nonviolent Conflict Between Autocracies⇤ Alex Braithwaite† Je↵rey Kucik‡ Jessica Maves§ September 29, 2012 ⇤ Paper to be presented at the Workshop on Data on Nonviolent Conflict, Uppsala (Sweden): October 11-12, 2012. This is a very rough draft. Please do not cite or circulate without permission. All remaining errors are our own. † Department of Political Science, University College London, alex.braithwaite@ucl.ac.uk ‡ Department of Political Science, University College London, j.kucik@ucl.ac.uk § Department of Political Science, Pennsylvania State University, jessica.maves@psu.edu 1 Introduction Domestic challenges to despotic governments appear to be contagious. Recent studies show that violent conflicts spread across borders in systematic ways (Buhaug & Gleditsch 2008; Braithwaite 2010; Maves & Braithwaite 2013). In this paper we ask: are nonviolent civil conflicts1 against autocratic regimes also contagious?2 If so, under what conditions? The unexpected eruption of the Arab Spring and its rapid spread highlight the importance of this question. The period from December 2010 to April 2011 was marked by the emergence of both violent and nonviolent conflicts across the majority of countries in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region. Each of these events seemed to contribute to contagion in the region, with rebels and opposition movements apparently motivated by actions taken by similar groups overseas3 — namely domestic organizations operating in comparable states (e.g., other autocracies). Contagion also helps explain the spread of Communist movements across East and Southeast Asia in the 1960s and 1970s, as well as the wave of protests and civil wars that accompanied democratization in post-Soviet Eastern Europe. It is cases such as these that motivate the present study.4 To answer the questions posed at the outset of this paper, we build upon the growing literature on the transnational causes of civil war (see, e.g., Lake & Rothchild 1998; Gleditsch 2007; Buhaug & Gleditsch 2008) and the emerging work on the efficacy of nonviolent resistance (c.f., Chenoweth & Stephan 2011). We o↵er two specific contributions. First, we argue that nonviolent movements inspire emulation within the family of autocracies. The occurrence of nonviolent movements signals to latent opposition groups (in other autocracies) that overcoming collective action problems is possible within the constraints facing domestic actors. Second, we recognize that these constraints vary. Not all would-be opposition groups have the same opportunities to act. Only in those autocracies where the opposition has had time to “mature” will the desire to emulate nonviolence 1 By ‘conflict’ we refer to campaigns in resistance to the established authority or government of the state. We employ this label with a view to referring to both violent and nonviolent forms. We use it interchangeably with resistance, instability, unrest, and rebellion. In this paper, we focus our attention upon accounting for patterns in nonviolent conflict. 2 We focus on autocracies in particular because this removes one source of variation and because autocracies are united in placing at least some constraints on the expression and activities of opposition groups. 3 Here, as is the case across the literature on contagion, “overseas” refers to other countries—both across oceans as well as across a land border. 4 Whilst we use the example of the Arab Spring to help motivate the research questions at the heart of our paper, we are not able to o↵er direct empirical analyses on the individual events of which it was comprised because of a lack of requisite data covering the period 2010—2012. 1 elsewhere translate into the ability to act domestically. We measure the opportunity to mature by looking at the length of time that an autocracy has had an elected national legislature. Elected legislatures provide the opposition opportunities to gain access to government. This, in turn, can lead to longer lasting, more ideologically coherent, and more experienced groups—i.e., the kind of groups that can e↵ectively overcome collective action problems once catalyzed by overseas examples. We test our argument using data on nonviolent campaigns within autocratic regimes between 1946 and 2006. Our models confirm the validity of our test hypotheses. They show, first, that nonviolence is contagious between autocratic states. When nonviolence occurs in one autocracy it significantly increases the likelihood of a movement occurring in another. Second, the results show that contagion is conditioned by the political context in which groups operate. While we assume that all domestic opposition groups look for exemplars of resistance outside of the state, our findings suggest that only those groups with long-established channels of opportunity (through which they oppose the regime) are able to convert the desire to emulate overseas nonviolence to action. The paper proceeds as follows. First, we discuss the dominant themes and logics of conflict contagion from the literatures on internal conflict and civil resistance. Second, we discuss the role of political institutions, opportunities, and opposition opportunities in the contagion of nonviolence. Third, we detail a research design to test the implications of our logic. Finally, we outline the results of our multivariate analyses and discuss their implications. 2 Background The proposition that conflict is contagious features prominently in both pessimistic prognoses of regional instability and optimistic opining about the potential for waves of revolutions against autocrats. Indeed, both views of contagion featured in popular discussions of the course and likely outcomes of the Arab Spring. On the one hand, countries such as Egypt and Algeria were said to be ripe for mass-led democratic change in the aftermath of government overthrow in Tunisia. On the other hand, commentators spoke cautiously of the danger of bloodshed as uprisings against dictators in Libya and Syria took hold. Herein, we seek to explain cases of the contagion of nonviolence, 2 such as that from Tunisia to Egypt and Algeria.5 The onset of new civil conflict episodes of this kind is most commonly explained by factors prevalent within the state. Poverty (Collier & Hoe✏er 2002; Collier et al. 2003; Fearon & Laitin 2003), ethnic diversity/dominance (Horowitz 1985, Hegre & Sambanis 2006), and a lack of political opportunity (Elbadawi & Sambanis 2002; Miguel, Satyanath, & Sergenti 2004) are frequently cited as causes of civil strife and wars. Much of this literature focuses upon explaining the onset of challenges that rely upon violent tactics. Kubik (1998) and Koopmans (2007) theorize that restrictions on access to policymaking channels and government more generally should lead to the radicalization of opposition groups and the increased probability of protests and strikes, a few elements of nonviolent conflict. In part as an e↵ort to cover the shortfall of domestic theories of civil conflict in accounting for new onsets, recent scholarship has established some principles regarding the transnational causes of civil conflict (c.f., Hill, Rothchild, & Cameron 1998; Gleditsch 2007). Again, much of this literature focuses attention upon cases in which campaigns adopted predominantly violent tactics. As part of this, a body of quantitative studies (see, e.g., Salehyan & Gleditsch 2006; Buhaug & Gleditsch 2008) has built upon Lake and Rothchild’s (1998) comprehensive treatment of the international contagion of conflict. Contagion refers here (both in this literature in general and in the current paper, more specifically) to the e↵ect that an event in one country has in increasing the probability of a similar event occurring in another country; or to put it another way, a circumstance in which “[p]rior adoption of a trait or practice in a population alters the probability of adoption for remaining non-adopters.” (Strang 1991, 325). For Elkins and Simmons (2005), apparent clusters of interdependent but uncoordinated decision-making of various kinds—including the di↵usion of innovations, policies, democratic regimes, and conflicts—occur because of one or both of two possible mechanisms: (a) another’s adoption alters the value of the practice and/or (b) another’s adoption imparts information. We refer here to the second of these two mechanisms of contagion as emulation, and it is the primary focus of this paper with respect to nonviolence. The emulation of tactics being used overseas is identified frequently within literature on the spread of protests and other forms of 5 The examples from the Arab Spring suggest that violence and nonviolence may also share some form of contagion. This is not the focus of this paper—aside from the inclusion in our empirical models of a single parameter controlling for violence overseas. This certainly warrants further investigation in future research, however. 3 nonviolence (McAdam 1988; Hill, Rothchild, & Cameron 1998). Hill, Rothchild, and Cameron (1998) o↵er an account of protest that critiques logics omitting transnational factors. They note that domestic political opportunities for nonviolent protest are only very slowly dynamic and exhibit considerable uncertainty. As such, they argue political opportunity structures that are conducive to protest are insufficient on their own to account for mass mobilization. Rather, new onsets of protest require the addition of a crucial catalyst for mobilization—namely, the demonstration of utility elsewhere.6 The catalyzing influence of overseas exemplars is also commonly cited as being central to processes of the di↵usion of democracy, and the influence of democratization upon conflict onset. Huntington (1991) identifies a demonstration e↵ect at the core of the so-called “Third Wave” of democracy, and Starr (1991) argues that geographic proximity is key to enabling the dissemination of knowledge regarding the value of democratization. Gleditsch and Ward (2006) demonstrate that countries are more likely to democratize if their neighbors are democratic and that democratization often results from a change in the relative power of domestic actors and their evaluation of political institutions. They argue that this changed position and perception is influenced by forces that are external, rather than internal, to the country. Whether designed to establish the sources of the spread of violence, democracy, or—as is the case here—nonviolence, we suggest that each of these explanations of contagion actually neglects to explain when and why the desire to emulate will prove practicable. In particular, we expect that an increase in nonviolence overseas is likely to increase the desire to emulate at home; however, emulation is only possible for a subset of groups: those that benefit from a long-established opportunity to oppose the regime. 3 Theory We begin by making two assumptions about politics within autocratic states. We assume that within the general population there exists some underlying desire for change that could mature into 6 Fox (2004) o↵ers an assessment of the potential for contagion of both violent and nonviolent forms of opposition of the state. His analysis o↵ers a somewhat confounding set of results given the logic and findings of the wider literature. Focusing exclusively upon religious movements, Fox demonstrates that contagious e↵ects are observed only for violent activities and not for nonviolent alternatives. He suggests that this may be unique to religious campaigns given that violence plays an intrinsic role in most religions. 4 a mass movement against the regime. In other words, there exists an inherent grievance against the government. We also assume that the leader(ship) of the state (the autocrat) prioritizes holding onto power and that this limits their interest in moving towards full democratization (Gandhi and Przeworski 2007; Magaloni 2008). Starting from those assumptions, we argue that two mechanisms help account for the potential contagion of nonviolent conflict across borders and for the escalation of grievance to conflict. First, external catalysts can encourage action at home by providing domestic groups with examples of successful mobilization abroad. In particular, we expect that potential nonviolent movements will pay most attention to events occurring in structurally-equivalent states (i.e. where opposition groups face similar conditions and struggles). Maves and Braithwaite (2013) demonstrate that this is true with respect to the contagion of civil wars, and we anticipate the same principle applies to nonviolent conflict as well. As such, this analysis focuses on the contagion of nonviolence among autocratic regimes. Second, the domestic institutional context determines the extent to which opposition groups, motivated by overseas activity, can e↵ectively overcome their own collective action problems. 3.1 Why Would Nonviolence Spread? There are strong theoretical reasons to expect that nonviolent conflict di↵uses around the global in a systematic manner. Existing research shows that actors seeking reform emulate examples of successful mobilization across a variety of policy domains. Emulation is shown to be the catalyst of, for instance, the imitation of innovation and policy adoption between U.S. states (Simmons & Elkins 2004, Volden 2006), the di↵usion of democratic institutions between countries globally (Starr 1991, O’Loughlin et al 1998), and the development of regional zones of peace and cooperation (Gleditsch 2002). In each of these areas, emulation results from information that hints at increases in incentives—i.e., from the prospect of an improvement in conditions (Elkins & Simmons 2005). Similar dynamics ought to apply to the contagion of nonviolence. A key premise of the logic of cross-national contagion is that opposition actors are inspired by actors overseas that have themselves challenged their governments. Examples of successful mobilizations abroad encourage latent domestic opposition groups to act. These examples show domestic groups that action is possible for groups who are constrained by non-democratic institutions and, by extension, who face 5 significant collective action problems. There are numerous sources of the collective action problem facing opposition groups. Chief among them are the costs that individuals bear when participating in an opposition movement. Individuals (or indeed groups) may not want to risk participating in opposition movements because of the repercussions doing so may have for their livelihoods and safety. Lost employment and potential imprisonment are just two of the risks that an individual may have to take in order to participate. These risks are then exacerbated by uncertainty over the outcome of an opposition movement. Ending up on the losing side of a campaign increased the likelihood of paying a high cost for participation. However, these costs are relatively low for nonviolent movements. To begin with, Chenoweth & Stephan (2011) argue and robustly demonstrate that nonviolent campaigns have a participation advantage over violent insurgencies, which is an important factor in determining campaign outcomes. The moral, physical, informational, and commitment barriers to participation are much lower for nonviolent resistance than for violent insurgency, which helps to attract greater levels of popular participation than violent conflict (Kurzman 1996; Chenoweth & Stephan 2011) Nonviolence is also associated with a relatively high likelihood of success. Existing research demonstrates quite starkly that a greater proportion of campaigns leading to the successful removal of governments and significant changes to state policies rely on nonviolent resistance (Chenoweth & Stephan 2011). The level and depth of participation is critical to determining the outcome of a resistance movement (DeNardo 1985; Lichbach 1994; Weinstein 2007; Wickham-Crowley 1992) and nonviolence consistently encourages greater participation because it has fewer associated costs and barriers (Kurzman 1996). Higher levels of (diverse) participation bring tactical and strategic advantages. Of 259 campaigns (of the 323 for which data were available), 80 nonviolent and 179 violent campaigns have very di↵erent average participation levels: 50,000 and 200,000, respectively. Moreover, 20 of the largest 25 campaigns were nonviolent (Chenoweth & Stephan 2011: chapter 2). The collective action problems that have to be overcome for nonviolent mobilizations are significantly lowers than those associated with violence. This has important implications for the contagion of political unrest. Existing work shows that violent movements spread across countries systematically. Domestic groups’ observations of violent movements in comparable countries increases the likelihood of violent action at home. Nonviolent movements are associated with lower barriers, and 6 should therefore also di↵use readily around the globe. We contend, therefore, that contagion depends upon the individual actor’s observation of (i) relatively low costs for participation and (ii) the belief that action can be successful. We argue that these precursors for contagion are likely in nonviolent movements. All else being equal, therefore, we expect that: Hypothesis 1. Nonviolent conflict spreads between autocratic states. 3.2 The Conditioning E↵ects of Domestic Institutions Our first hypothesis rests squarely upon the well established conclusion that the barriers to and costs associated with participation in nonviolence are low, or at least are lower than those associated with participation in violent campaigns. However, as much as an opposition group may wish to emulate exemplars of nonviolence overseas, they require time, e↵ort, and resources to be able to recruit the large numbers required to sustain a nonviolent campaign. An organization must have been founded. Some experience with opposition is required. Time is required to facilitate the development of trust within the movement. In sum: opposition groups need more than the desire to mobilize. They also need the opportunity. We argue that opposition movements must “mature” in order for emulation of nonviolence to be a practicable option. Indeed, much of the literature addressing the onset of civil conflict wrestles with how rebels are able to overcome key collective action problems that undermine the kind of mobilization and participation upon which resistance movements depend (Lichbach 1995, Weinstein 2005). The social movement literature o↵ers at least two major accounts of mobilization that are germane to understandings of conflict onset and contagion. Political opportunity structure (POS) arguments center upon the fundamental premise that collective action is encouraged (or, indeed, discouraged) by the characteristics and dimensions of the prevailing political environment— including but not limited to key institutions of government (c.f., Tarrow 1998). POS theories have been very widely employed; it has been claimed that, “most contemporary theories of revolution start from much the same premise, arguing that revolutions owe less to the e↵orts of insurgents than to the work of systemic crises which render the existing regime weak and vulnerable to challenge from virtually any quarter” (DeNardo 1985: 24). By contrast, resource mobilization theories (RMT) 7 tend to argue that mobilization occurs most efficiently when resources converge around a set of shared preferences. Within autocratic states, the maturation of an opposition requires political opportunities which a↵ord citizens a chance to identify and organize with others who hold similar beliefs and grievances. The presence of a legislature in an autocracy provides an indication that opposition forces are at least minimally organized and can no longer be bought o↵ with rents (Gandhi and Przeworski 2006). As Maves and Braithwaite (2013) argue, elected legislatures provide openings in the structures of an autocratic state that are regularly associated with the absence of violent conflict when the state resides in a conflict-free neighborhood, but with the contagion of violent conflict when the state resides in a conflict-ridden neighborhood.7 They demonstrate that this is the case because these institutional structures serve as a sufficient concession by the dictator to the opposition when the balance of power still rests firmly with the regime, but violence in other states increases the opposition’s strength relative to the regime. With respect to the emulation of nonviolence, the longevity of these institutional openings and opportunities (rather than their mere existence) plays a crucial role. In order for movements and campaigns to achieve a critical threshold sufficient to sustain a large-scale challenge against the autocrat requires an adequate maturation period. Returning to the example of the Arab Spring, countries with young or nonexistent elected legislatures experienced the onset of violent conflict: Libya has been without an elected legislature since 1969, and Bahrain only established their legislature in 2003. Conversely, countries that had a long history of elected institutions a↵ording the opposition a chance to mature organizationally tended to be faced with nonviolent challenges. Egypt has had a popularly-elected legislature since 1964, and Tunisia since 1958. Hypothesis 2. The likelihood of emulation of nonviolent conflicts between autocracies is conditioned by the longevity of political openings, with states enjoying a longer period of maturation for opposition movements most likely to be a↵ected by contagion. 7 For example, peace prevailed in Niger following the establishment of an elected legislature. However, this peace was short-lived. In 1991 the Tuaregs, unhappy about the regime’s unwillingness to make further compromises with respect to autonomy, initiated a civil war against the Nigerien government, aided in large part by arms flows and inspiration from other conflicts in the region. Importantly, though, not all autocratic legislatures are windowdressings. As an illustration of this point, the o↵er to give the Jordanian Muslim Brotherhood’s political organization more control over the legislative agenda concerning religious issues was sufficient to cause the group to call o↵ massive protests against the regime (Schwedler 2006). 8 4 Research Design Our tests employ explanatory variables relating to conflict experience and institutional design within autocracies. Accordingly, we limit our analyses to autocracies. While a variety of data sets exist to assess dimensions of (and di↵erences among) autocratic regimes, we use the data collected by Cheibub, Gandhi, and Vreeland (2010; henceforth CGV) due to its wealth of information about the institutions in these regimes. In keeping with the CGV definition, we code autocracies as those regimes in which at least one of the following conditions is not met: both the legislature and the executive are elected, multiple political parties outside the influence of the regime exist and compete in these elections, and executive power has been handed over peacefully between parties as the result of elections.8 140 countries are represented in this population of autocracies from 1946 to 2006, with the country-year as our unit of observation. Dependent Variable This paper explores the e↵ect of nonviolence overseas and political opportunities at home on the prospects for nonviolent challenges against local autocrats. The dependent variable is a binary indicator of whether a new campaign of nonviolence against the government breaks out in an autocracy i in year t. We code this variable as “1” for every country-year in which a new campaign onset is predominantly nonviolent and “0” otherwise. We utilize data from Chenoweth and Stephan (2011) detailing 323 cases of violent and nonviolent resistance between 1900 and 2006. These data include details of e↵orts to achieve regime change, the expulsion of foreign occupiers, and/or secession. We include only the cases of nonviolence in our analyses, although we do control for the occurrence of violence overseas. We observe 142 onsets of nonviolent resistance in autocracies in the post-WWII period; 49 of these break out in autocracies without an elected legislature, while the remaining 93 are fought in autocracies with an elected legislature. Explanatory Variables We construct a measure of conflict in the population of autocracies that captures the rate of conflict 8 Because of this last rule, countries like Botswana and South Africa, as well as Japan and Mexico for most of the period in this study, are considered to be non-democratic. Dropping the few countries which do not experience executive turnover does not a↵ect our results. 9 amongst structurally-equivalent countries. The emulation mechanism of contagion is expected to work most efficiently when valid reference groups are observable by potential adopters. This is because potential adopters are likely to pay attention first to events and policies in similar countries or contexts (Elkins & Simmons 2004: 45); that is to say that the observation of similar cases nearby (in a social sense) reflects a cognitive heuristic in the calculation of utilities. For example, the Otpor resistance movement in Serbia, which was integral in the 2000 removal of Slobodan Milosevic from office, is said to have inspired several similar movements around the world, including the Bolga movement in Uzbekistan opposing the dictator Islam Karimov, and the April 6 Youth Movement, which has been active in Egypt in recent years. Practically, this is measured as the percentage of all other autocracies in the international system that experienced an ongoing campaign of nonviolence in the previous year. This continuous variable conceptualizes a “neighborhood” as being comprised of countries that are institutionally similar to one another, thereby providing a means to test the potential for emulation between opposition groups faced with analogous political conditions.9 Again, these data are drawn from Chenoweth and Stephan (2011). This variable, Nonviolence Overseas, serves as our primary explanatory variable for tests of Hypothesis 1, and it is one of the constituent terms in our test of Hypothesis 2, which requires an interaction term.10 The other constituent term in the interaction needs to capture di↵erent legacies of opposition formation and types of institutional designs within autocracies. In an ideal scenario, we would operationalize the concept of longevity of oppositional opportunity by measuring organizational characteristics of the population of potential rebels and opposition movements within the state that might choose to challenge the authority of the central government. Unfortunately, what little data exists on rebel groups typically only characterizes those groups whose ambitions to raise arms are actually realized (see, e.g., Cunningham et al. 2009). These data are not, therefore, available for those latent challengers who are not able or willing (for whatever reason) to actually engage in 9 While we recognize that physical distance may be important, we believe it to be secondary to having a more substantive reference group. Given that we cannot empirically consider the composition of opposition groups given the lack of available data, the best alternative is to look at a similarity of situational contexts. However, our results are robust to model specifications using a physical distance-based measure in place of this measure of structural equivalence. 10 We preference employment of a non-geographic measure of the neighborhood both because of the reference group concept of Elkins and Simmons—as noted above—and because there are some quite stark examples of alleged emulation across considerable geographic ranges. 10 a campaign of resistance. Thus, we opt to identify a proxy for this concept. In doing so, we prioritize a measure that (i) is available for the full set of autocratic states11 , (ii) is available throughout a long temporal domain12 , and (iii) reflects a period of time during which opposition movements may plausibly have been able to mature sufficiently to mount and sustain a nonviolent challenge against the government. For this purpose we rely upon a measure that characterises openings and opportunities in the political institutions of the state. Specifically, we measure the number of years for which a state’s current elected legislature has been in place. We do so by drawing upon one measure from the CGV dataset. Their indicator variable Closed is a three-category coding of the nature of the country’s legislature. This variable is coded “0” if the legislature does not exist, “1” if the legislature is appointed, and “2” if the legislature is elected. From this, we first generate a dummy variable to indicate whether the autocracy had an elected legislature on 1 January of the observed year.13 We then generate from this a measure, Age of Legislature, which counts the number of years that the state has had an elected legislature. This variable ranges from 0 (the state does not have an elected legislature) to 62 years with an elected legislature. Control Variables We include a standard set of control variables from studies of civil conflict onset in both of our model specifications. First, we include the natural log of GDP per capita, lagged one year. Economic development typically has a robust negative relationship with the probability of violent conflict onset and there is good reason to suspect that the same relationship would hold for nonviolence, too. Second, we use the natural log of the population of a country, which is expected to be positively correlated with the likelihood of all varieties of conflict onset. Both of these variables come from Maddison (2010). Third, we include an indicator of the level of violent conflict in the population of autocratic states 11 Data on freedoms and rights to associate and organize tend only to be available for a subset of countries and their measurement commonly relies upon media reporting, which is often highly unreliable in autocratic states. 12 Again, data on freedoms and rights to associate and organize tend to only be available for the period post-1980 or so. 13 As was true in Maves and Braithwaite (2013), we use the more restrictive coding of ‘elected’ (rather than appointed) legislatures only, as the process of elections suggests that the dictator has made an additional concession to the opposition by foregoing his ability to hand-pick members of the institution, and as a result he may not have much else to give in order to appease the opposition—short of democratizing completely. 11 in the previous year. This variable captures the weighted minimum distance between autocracy i and civil wars in other autocracies j, by normalizing the inverse of the distance between autocracies i and j by the sum of the inverse distances between i and all other autocracies j.14 Higher values of this variable indicate that most autocracies in the international system experienced violent conflict, or—more likely—that an autocracy or set of autocracies in close proximity to i were host to a civil war in the previous year. The data on civil wars come from the Uppsala/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset (Gleditsch et al. 2002, Harbom and Wallensteen 2010), which defines an internal armed conflict as fighting between the government of a country and one or more internal opposition group(s) resulting in at least 25 deaths per year. Fourth, we control for the proportion of neighbors that are coded as democracies in the CGV dataset to account for the level of democracy in the neighborhood, lagged one year. Neighbors are defined as those countries whose territories are separated by not more than 950 km.15 We use data from the CGV dataset rather than the oft-employed Polity data because the latter has been shown by Vreeland (2008) to be endogenous to the process of civil war onset, and thus it cannot produce reliably unbiased results. We expect that countries in more democratic neighborhoods should be less likely to experience the onset of nonviolent campaigns than their counterparts in more autocratic neighborhoods. We are mindful, though, that this relationship may not be quite as strong as that typically found in models of violent campaigns. Fifth, we construct a binary variable to indicate the end of the Cold War period, as this has been shown to increase not only the likelihood of countries democratising their institutions of government but also the likelihood of mass protests and conflict. Last, we include a variable that accounts for the number of years since the autocracy last experienced a nonviolent campaign. We also include the squared and cubic polynomials of this variable to control for the possibility of temporal non-monotonicity (Carter and Signorino 2010). Summary statistics of the variables used in this study are reported in Table 1. 14 Further detail on the conceptual and operational definitions and construction of this variable is available in Maves and Braithwaite (2013) as well as the study by Buhaug and Gleditsch (2008). 15 We also constructed this variable using higher minimum distance constraints, as well as more specific institutional characteristics—namely, the proportion of autocratic neighbors with elected legislatures. Results were consistent for all measures used. 12 5 Discussion of results The results of our multivariate analyses are detailed in Table 2. To assess the validity of our hypotheses, we present a pair of tests to address two related questions. First, we investigate whether the occurrence of nonviolence in other autocracies increases the likelihood of nonviolence in the home autocracy (Model 1). Second, we look more closely at the conditioning e↵ect that domestic opportunities to organize against the government have upon this contagion (Model 2). Both models are specified as probit regressions, with the same set of control variables and robust standard errors clustered by country. Model 1 includes the independent measures of legislature age (our proxy for the opposition maturation concept) and nonviolence overseas. Model 2 additionally includes the interaction of these two component parts. Table 2 about here The coefficient on Nonviolence Overseas is positive and strongly significant in Model 1, which supports the idea that nonviolence is contagious and thereby provides strong initial confirmation of Hypothesis 1. A one standard deviation increase in the proportion of autocracies overseas that experienced nonviolence in the previous year (this reflects an increase from 4.7% to 8.4% of autocracies) is associated with a 38 percent increase in the predicted probability of the onset of a new nonviolent campaign at home. This same model returns a negative but statistically insignificant coefficient on the parameter estimate of Age of Legislature, which suggests that, ceteris paribus, the longevity of the opportunity to oppose the regime does not have an independent bearing upon the likelihood of nonviolent onset across the whole population of autocracies. However, it is possible that the e↵ect of this variable changes across contexts: namely, that older legislatures (and, in keeping with our theory, the longevity of opportunities for opposition) decrease the likelihood of nonviolent conflict when opposition groups are not particularly inspired to dramatically challenge the status quo, whereas the occurrence of nonviolent conflict elsewhere inspires emulation—which is especially possible when a group exist in an autocracy with long-running opportunities for opposition. In Model 2, once we additionally include the interaction between these two key explanatory variables, we find some consistency and an important change in the factors predicting the onset of nonviolence in autocracyi . Specifically, while the coefficient on Nonviolence Overseas remains 13 positive and statistically significant, the coefficient on Age of Legislature remains negative but dramatically increases in statistical significance. In the presence of the term capturing the interaction of these two continuous variables, these coefficients can only cautiously be interpreted as reflecting the impact of the variable when its counterpart is equal to 0. Accordingly, this model indicates, first, that increases in levels of nonviolence overseas do have a positive influence upon the probability of nonviolence at home amongst the set of autocracies without an elected legislature—those autocracies for which Age of Legislature is equal to zero. Second, this model shows that autocracies with older legislatures (and, therefore, potentially more mature opposition movements) are much less likely to observe the onset of nonviolence when other autocracies in the world are free from nonviolent conflict. These are both interesting conclusions, and the first point is still consistent with the logic of our first hypothesis. More pertinent to the task at hand, however, is the interpretation of the coefficient on the interaction term. This is positive and strongly significant, indicating that the contagious e↵ect of nonviolence overseas (Hypothesis 1) exists most strongly at older ages of the elected legislature within the autocracy. This finding appears consistent with the conditioning logic underlying Hypothesis 2. It appears as if nonviolence is most likely to spread to those autocracies in which there potentially exists a mature opposition movement practiced in opposing the government. Given that both of our explanatory variables of interest are continuous, however, it is crucial and certainly more informative to view predicted probabilities (detailing the substantive e↵ects of the variables) in graphical form. As an example, we plot the predicted probability of nonviolent onset based on the specification from Model 2. Figure 1 details the predicted probability (on the y-axis) of the onset of a new nonviolent campaign at home that is associated with increases in the proportion of autocracies overseas experiencing nonviolent challenges (the x-axis). The graph compares this relationship for low (25th percentile = 0 years) and high (75th percentile = 16 years) illustrative values of the age of the elected legislature–our measure of the opportunity for opposition maturation. Figure 1 about here Figure 1 demonstrates, as expected by Hypothesis 1, that the predicted probability of nonviolence at home increases consistently as the proportion of autocracies globally experiencing nonviolent challenges increases. This is the case in both autocracies with young (the dashed green line) 14 and old (the solid orange line) elected legislatures. Importantly, whilst the confidence intervals associated with the two illustrative predictions remain marginally overlapped across the full range of values of nonviolence overseas, the point predictions themselves do diverge quite notably as the proportion of autocracies overseas experiencing nonviolence increases. As predicted by Hypothesis 2, the e↵ect of nonviolence overseas appears to be conditioned by the age of the domestic political context. In years with relatively low levels of nonviolence occurring overseas, autocracies with older elected legislatures actually appear to experience lower levels of nonviolence at home than do those with young legislatures. However, in years with higher levels of nonviolence overseas, this relationship is reversed: those autocracies with older elected legislatures—i.e., those with the more durable opportunities for opposition maturation—are actually more likely to experience nonviolence at home. 6 Concluding remarks This article tests whether nonviolent conflicts spread between states in a systematic manner. The literature on civil conflict demonstrates that violence is contagious. There are strong theoretical reasons to expect that nonviolence follows similar patterns. By comparison, nonviolent forms of resistance are much more likely to motivate mass participation and, not coincidentally, to achieve their goals than are their violent campaigns. These two traits imply that opposition groups have much more manageable collective action problems to overcome. When they observe a successful mobilization overseas, latent domestic opposition groups can choose to act against their own regime. However, not all groups are a↵orded the same opportunities to emulate examples in other autocracies. The domestic political constraints in which groups operate vary significantly and this variation has important implications for whether a group can mobilize. Our analysis demonstrates that the net e↵ect of nonviolence overseas is positive—i.e., nonviolence is contagious. However, this e↵ect is not equal for all autocracies. The conditional relationship between domestic politics and overseas events is such that in addition to having an example to follow, emulation requires the opportunity for the existence of a sufficiently mature opposition in order for emulation (and, thus, contagion) to be realized. The results o↵er a number of contributions as well as opening new avenues for future research. 15 First, they show that nonviolent movements are contagious. This is a nontrivial finding given the important implications nonviolence has for mass mobilization, successful campaign outcomes, and durable peace. Nonviolence is significantly more likely to lead to the successful resolution of a conflict and longer term stability. Second, we help specify the conditions under which the desire to mobilize translates into political action. Domestic institutional contexts play an important role in conditioning the efficacy of examples of successful movements overseas. Only when domestic opposition groups have had time to “mature” can we expect to observe clear patterns of emulation. This final point suggests that more work has to be done before we fully understand how political institutions shape the likelihood of conflict onset via contagion. Work already exists in the areas of interstate and civil war on the role played by (non-)democratic institutions. However, we know comparatively little about how domestic political institutions amplify, or dampen, cross-national sources of conflict outbreak. 16 References Braithwaite, Alex. 2010. “Resisting infection: How state capacity conditions conflict contagion.” Journal of Peace Research 47(3): 311–319. Buhaug, Halvard; Gleditsch, Kristian Skrede. 2008. “Contagion or Confusion? Why Conflicts Cluster in Space1.” International Studies Quarterly 52(2): 215–233. Carter, David B., and Curtis S. Signorino. 2010. “Back to the Future: Modeling Time Dependence in Binary Data.” Political Analysis 18(3): 271–292. Cheibub, Jose Antonio, Jennifer Gandhi, and James Raymond Vreeland. 2010. “Democracy and Dictatorship Revisited.” Public Choice 143(1): 67–101. Chenoweth, Erica, and Maria J. Stephan. 2011. Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict. New York: Columbia University Press. Collier, Paul, and Anke Hoe✏er. 2002. “On the Incidence of Civil War in Africa.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 46(1): 13–28. Collier, Paul, V.L. Elliott, Havard Hegre, Anke Hoe✏er, Marta Reynal-Querol, and Nicholas Sambanis. 2003. Breaking the Conflict Trap: Civil War and Development Policy, Volume 1. World Bank. Cunningham, David E., Kristian Skrede Gleditsch, and Idean Salehyan. 2009. “It Takes Two: A Dyadic Analysis of Civil War Duration and Outcome.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 53(4): 570–597. DeNardo, James. 1985. Power in Numbers. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. Elbadawi, Ibrahim, and Nicholas Sambanis. 2002. “How Much War Will We See?: Explaining the Prevalence of Civil War.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 46(3): 307–334. Elkins, Zachary, and Beth Simmons. 2005. “On Waves, Clusters, and Di↵usion: A Conceptual Framework.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 598(1): 33– 51. 17 Fearon, James D., and David D. Laitin. 2003. “Ethnicity, Insurgency, and Civil War.” American Political Science Review 97(1): 75–90. Fox, Jonathan. 2004. “Is Ethnoreligious Conflict a Contagious Disease?” Studies in Conflict and Terrorism 27(2): 89–106. Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski. 2006. “Cooperation, Cooptation, and Rebellion under Dicatorships.” Economics & Politics 18(1): 1–26. Gandhi, Jennifer, and Adam Przeworski. 2007. “Authoritarian Institutions and the Survival of Autocrats.” Comparative Political Studies 40(11): 1279–1301. Gleditsch, Kristian S. 2007. “Transnational Dimensions of Civil War.” Journal of Peace Research 44(3): 293–309. Gleditsch, Kristian S., and Michael D. Ward. 2006. “Di↵usion and the International Context of Democratization.” International Organization 60(4): 911–933. Gleditsch, Kristian Skrede. 2002. All International Politics is Local: The Di↵usion of Conflict, Integration, and Democratization. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. Gleditsch, Nils Petter, Peter Wallensteen, Mikael Eriksson, Margareta Sollenberg, and Håvard Strand. 2002. “Armed Conflict 1946–2001: A New Dataset.” Journal of Peace Research 39(5): 615–637. Harbom, Lotta, and Peter Wallensteen. 2010. “Armed Conflicts, 1946—2009.” Journal of Peace Research 47(4): 501–509. Hegre, Håvard, and Nicholas Sambanis. 2006. “Sensitivity Analysis of Empirical Results on Civil War Onset.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 50(4): 508–535. Hill, Stuart, Donald Rothchild, and Colin Cameron. 1998. “Tactical Information and the Di↵usion of Peaceful Protests.” In The international Spread of Ethnic Conflict: Fear, Di↵usion, and Escalation, ed. David A. Lake, and Donald S Rothchild. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Horowitz, Donald L. 1985. Ethnic Groups in Conflict. Berkeley: University of California Press. 18 Huntington, Samuel P. 1991. The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. Koopmans, Ruud. 2007. “Protest in Time and Space: The Evolution of Waves of Contention.” In The Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, ed. David A. Snow, Sarah A. Soule, and Hanspeter Kriesi. Blackwell Publishing Ltd. Kubik, Jan. 1998. “Institutionalization of Protest During Democratic Consolidations in Central Europe.” In The Social Movement Society: Contentious Politics for a New Century, ed. David S. Meyer, and Sidney Tarrow. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield. Kurzman, Charles. 1996. “Structural Opportunity and Perceived Opportunity in Social-Movement Theory: Evidence from the Iranian Revolution of 1979.” American Sociological Review 61(1): 153–170. Lake, David A., and Donald S Rothchild. 1998. The international spread of ethnic conflict: fear, di↵usion, and escalation. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. Lichbach, Mark. 1995. The Rebel’s Dilemma. Ann Arbor, MI.: University of Michigan Press. Maddison, Angus. 2010. “Dataset: Statistics on World Population, GDP, and Per Capita GDP, 1–2008 AD.” http://www.ggdc.net/MADDISON/oriindex.htm . Magaloni, Beatrice. 2008. “Credible Power-Sharing and the Longevity of Authoritarian Rule.” Comparative Political Studies 41: 715–741. Maves, Jessica, and Alex Braithwaite. 2013. “Autocratic Institutions and Civil Conflict Contagion.” Journal of Politics forthcoming. McAdam, Doug. 1988. “Micro-mobilization Contexts and Recruitment to Activism.” In From Structure to Action: Social Movement Participation Across Cultures, ed. Bert Klandermans, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Sidney Tarrow. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Miguel, Edward, Shanker Satyanath, and Ernest Sergenti. 2004. “Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict: An Instrumental Variables Approach.” Journal of Political Economy 112(4): 725–753. 19 O’Loughlin, John, Michael D. Ward, Corey L. Lofdahl, Jordin S. Cohen, David S. Brown, David Reilly, Kristian S. Gleditsch, and Michael Shin. 1998. “The Di↵usion of Democracy, 1946–1994.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88(4): 545–574. Salehyan, Idean, and Kristian Skrede Gleditsch. 2006. “Refugees and the Spread of Civil War.” International Organization 60(02): 335–366. Schwedler, Jillian. 2006. Faith in Moderation: Islamist Parties in Jordan and Yemen. Cambridge Univ. Press. Starr, Harvey. 1991. “Democratic Dominoes: Di↵usion Approaches to the Spread of Democracy in the International System.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 35: 356–381. Strang, David. 1991. “Adding Social Structure to Di↵usion Models: An Event History Framework.” Sociological Methods and Research 19(3): 324–353. Tarrow, Sidney. 1998. Power in Movement: Social Movements and Contentious Politics. Cambridge University Press. Volden, Craig. 2006. “States as Policy Laboratories: Emulating Success in the Children’s Health Insurance Program.” American Journal of Political Science 50: 294–312. Vreeland, James Raymond. 2008. “The E↵ect of Political Regime on Civil War.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 52(3): 401–425. Weinstein, Jeremy M. 2005. “Resources and the Information Problem in Rebel Recruitment.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 49(4): 598–624. Wickham-Crowley, Timothy. 1992. Guerrillas and Revolution in Latin America: A Comparative Study of Insurgents and Regimes since 1956. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. 20 Table 1: Summary statistics Variable Mean Std. Dev. Nonviolence Onset 0.028 0.164 Age of Legislature 10.143 12.713 Nonviolence Overseas 0.047 0.036 Nonviolence Overseas*Age of Legislature 0.539 0.950 Violence in the Neighborhood 0.184 0.246 Democracy in the Neighborhood 0.28 0.263 ln(GDPpc)t 1 7.517 0.891 ln(Population) 8.904 1.565 Post-Cold War 0.307 0.461 Peace Years 12.899 12.952 Peace Years (squared) 334.1 539.486 Peace Years (cubed) 10850.613 24448.816 21 Min. 0 0 0 0 0 0 5.333 4.111 0 0 0 0 Max. 1 62 0.15 6.437 0.997 1 10.667 14.097 1 63 3969 250047 N 5120 5120 4969 4969 5033 4974 4524 4577 5120 5120 5120 5120 Table 2: The Contagion of Nonviolent Conflict, 1946—2006 Model 1 Model 2 Nonviolence Overseas 5.808⇤⇤⇤ 3.287⇤⇤ Age of Legislature (0.996) (1.227) -0.004 -0.020⇤⇤ (0.004) (0.007) 0.213⇤⇤ Nonviolence Overseas*Age of Legislature (0.071) Violence in the Neighborhood Democracy in the Neighborhood ln(GDPpc)t 1 ln(Population) Post-Cold War Peace Years Constant Log likelihood No. of observations 0.257# 0.238# (0.138) (0.138) 0.339# 0.307# (0.180) (0.176) -0.033 -0.026 (0.047) (0.047) 0.119⇤⇤⇤ 0.119⇤⇤⇤ (0.022) (0.023) -0.215⇤ -0.164# (0.090) (0.087) -0.032# -0.033# (0.018) (0.018) -2.971⇤⇤⇤ -2.893⇤⇤⇤ (0.395) (0.403) -564.902 4330 -560.472 4330 Notes: Significance levels (two-tailed): ⇤: 95% ⇤⇤: 99% ⇤ ⇤ ⇤: 99.9%. Coefficients with robust standard errors in parentheses. Models estimated with squared and cubed polynomials of Peace Years, not reported here (n.s.). 22 Predicted Probability of Nonviolence at Home .15 0 .05 .1 Figure 1. Predicted Probabilities from Model 2 0 .05 .1 Nonviolence Overseas Low Age of Leg. 23 High Age of Leg. .15