A Reexamination of the Political Economy of Growth in

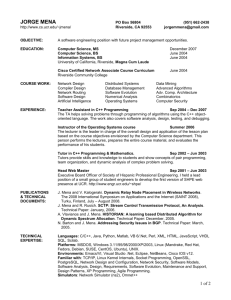

advertisement