Masculinity in Silas Marner

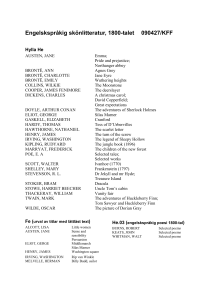

advertisement