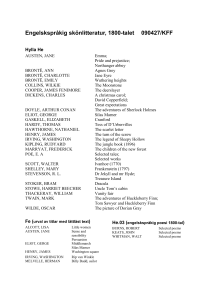

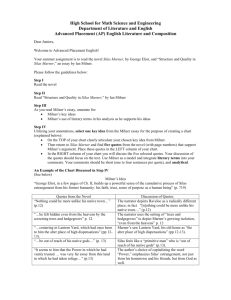

Structure and Quality in Silas Marner

Rice University

Structure and Quality in Silas Marner

Author(s): Ian Milner

Source: Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900, Vol. 6, No. 4, Nineteenth Century (Autumn,

1966), pp. 717-729

Published by:

Rice University

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/449365 .

Accessed: 30/05/2013 11:19

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

.

Rice University is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Studies in English

Literature, 1500-1900.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Structure and Quality in Silas Marner

I A N MI LNER

Eliot's other novels, even of the early period. Its simple, com- pact design and special tone suggest the moral fable. Born of

"a sudden inspiration" which "came across my other plans"'1 the story has a freshness, an easy-running yet disciplined flow, a varied and surely focussed narrative control, an unerring command of character portrayal of a certain range, and a flexible rendering of dialogue, such as George Eliot scarcely ever bettered. These and other graces have earned it the title of "that charming minor masterpiece."2 The limiting judgment is underlined: "But in our description of the satisfaction got from it, 'charm' remains the significant word."3

Whatever George Eliot intended, she brought off some- thing other than a pleasant piece of pastoral injected with some "moral truth." She was herself conscious of the deeper implications of her theme. She had to reassure Blackwood that, though "rather sombre" at the beginning:

I hope you will not find it at all a sad story, as a whole, since it sets-or is intended to set-in a strong light the remedial influences of pure, natural human relations.4

Though she promised Blackwood the story's "Nemesis" was

"a very mild one" the moral terrain traversed reveals matters strange to pastoral. Charm there is, fresh and spontaneous in the set choral scenes at the Rainbow Inn, the Casses' New

Year's Eve dance, in the glimpses of Silas learning a fa- ther's part, and in the natural vigour of Dolly Winthrop. Yet something else emerges, of more far-reaching and sombre aspect, that defines the tale and its quality as art equally with the charm of the pastoral scenes or the narrative grace.

George Eliot told Blackwood that Silas Marner

'G. S. Haight, The George Eliot Letters, New Haven, 1954-55, III, p. 171. aF. R. Leavis, The Great Tradition, New York: Doubleday Anchor-

Books, 1954, p. 62. lLeavis, p. 63.

'Haight, III, p. 382.

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

718 S I L A S M A R N E R came to me first of all, quite suddenly, as a sort of legendary tale ... but, as my mind dwelt on the subject,

I became inclined to a more realistic treatment.5

In the tension between the "legendary" and the "realistic" components, considered in their joint relation to the struc- ture of values unfolded in the tale, lies its full meaning and appeal.

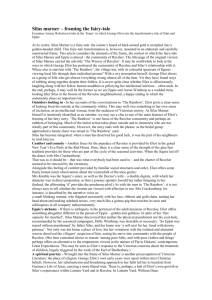

Silas stands at the center of the legendary element. In the opening pages he is introduced, by name only, the shad- owy figure of a linen-weaver who has migrated to Raveloe from "an unknown region called North'ard." He is an alien, living in chosen isolation from the village community. His trade alone makes him suspect: the "mysterious action" of his loom fascinates yet awes the Raveloe lads. If they merely glanced in his window he would fix on them a "dreadful stare" such as "could dart cramp, or rickets, or a wry mouth" at any one of them. The village shepherd was not sure whether the weaver's trade "could be carried on entirely without the help of the Evil One."

Silas, at the outset, gives the impression of a presence, not of an individualized personality. When we are carried back fifteen years to Lantern Yard we have a momentary glimpse of a devout but featureless young man, wholly ab- sorbed by his faith (marriage is just a further link with the sacrament). What matters, and what stands out in the tell- ing, is the wrong done to Marner-the cold malice of a friend that destroys his place in the community, cuts off his marriage, and blasts his faith: "there is no just God that governs the earth righteously, but a God of lies, that bears witness against the innocent" (Ch. I).

The force of Silas's blasphemy, coming from one whose faith was his life, measures the scale of the evil he has en- countered. He turns his back on the ruptured community of trust and fellowship which previously had been his only medium of existence. He denies and flees from the divine will that has betrayed his trust. George Eliot hints there was something animistic in his escape from the numen of

Lantern Yard: "And poor Silas was vaguely conscious of something not unlike the feeling of primitive men, when they fled thus, in fear or in sullenness, from the face of an un- propitious deity" (Ch. II).

6Haight, III, 382.

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I AN MILNER 719

In his Raveloe cottage Marner lives in isolation for fifteen years. His brief attempt to enter the community by treating the sick with herbs only widens his separation and confirms distrust as to the sources of his knowledge. Work is his anodyne, the golden guineas his only god. George Eliot, in a few pages of Ch.II, builds up a powerful sense of the cu- mulative process of Silas's estrangement from his former humanity: his faith, trust, sense of purpose as a human being. His work now is carried on without aim: he weaves

"like the spider, from pure impulse, without reflection."

The web is the familiar image used in the novels to suggest the narrowing of vision from egoism or lack of fellowship.

He lives at a sub-human level, his life reduced "to the un- questioning activity of a spinning insect." In a different image George Eliot underlines his dehumanization:

Strangely Marner's face and figure shrank and bent themselves into a constant mechanical relation to the objects of his life, so that he produced the same sort of impression as a handle or a crooked tube, which has no meaning standing apart. (Ch.II)

This is surely one of the most powerful instances of meta- phor used to evoke character transformation. Marner is re- duced to the world of objects, thingified. His human essence has "no meaning standing apart." The image springs from the immediate environment: it is more effective than the somewhat related but less naturally concrete metaphor of

Isabel Archer's disillusion:

She saw . . . the drying staring fact that she had been an applied handled hung-up tool, as senseless and convenient as mere shaped wood and iron.6

The intensity of Marner's attachment to things leads to fetishism: the money not only grew, but it remained with him.

He began to think it was conscious of him, as his loom was, and he would on no account have exchanged those coins, which had become his familiars, for other coins with unknown faces. (Ch.II)

Cut off from human relations, Silas lives with the "faces"

'Henry James, The Portrait of a Lady, ch. 52: cited by W. J. Harvey in his discussion of settings as "metonomic, or metaphoric, expressions of character," Essays in Criticism XIII, i (Jan., 1963), 62.

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

720 S I L A S M A R N E R of coins, which he draws out at night "to enjoy their com- panionship." His old brown earthenware pot, in which he fetches water, is for twelve years his companion . . . always lending its handle to him in the early morning, so that its form had an expression for him of willing helpfulness.. .. (Ch.II)

And, in a superb proleptic image, he thought fondly of the guineas that were only half earned by the work in his loom, as if they had been unborn children-thought of the guineas that were coming slowly through the coming years, through all his life.... (Ch.II)

The irony of the image is doubly weighted: there is an echo of the loss of Silas's earlier human impulse to marry and have children and a foretokening of the nemesis that is to rob him of his guineas while giving him "gold" in other kind.

George Eliot makes use of choric scenes very effectively to suggest the warmth and vitality of the Raveloe popular community. And alongside this pulsing communal life from which he has isolated himself, Silas's alienation is felt more starkly by the reader. The night he loses his gold Silas is driven, ironically, to seek redress from his fellow-man. The spiritedly and solidly rendered Rainbow Inn company (Ch.VI), whose individual quirks and petty animosities do not break down but merely variegate the overall sense of community, forms a choric scene that throws into high contrast Silas's abrupt and otherworldly irruption: "the pale thin figure of

Silas Marner was suddenly seen standing in the warm light, uttering no word, but looking round at the company with his strange unearthly eyes" (Ch.VII).

The other major use of a choric scene as an image of com- munal life-the New Year's Eve dance at the Red House- is yet more developed and, from its timing and placing, more effective in aesthetic strategy. Its immediate background is filled in by the attempts of Mr. Macey and of Dolly Winthrop to bring Marner into the community by persuading him to go to church, especially on Christmas day. The sense of

Silas's alienness is tragicomically suggested in the scene where he confesses to an amazed Dolly that he has never been

"to church," only "to chapel" (the "new word" puzzled Mrs.

Winthrop: "she was rather afraid of inquiring further, lest

'chapel' might mean some haunt of wickedness" [Ch.X]).

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IAN MILNER 721

Mrs. Winthrop's lard-cakes and persuasions cannot free

Marner from his enwalled isolation. He spends Christmas

Day alone. The Nature scene is finely used to image his condition:

In the morning he looked out on the black frost that seemed to press cruelly on every blade of grass, while the half-icy red pool shivered under the bitter wind; but towards evening the snow began to fall, and cur- tained from him even that dreary outlook, shutting him close up with his narrow grief. And he sat in his robbed home through the livelong evening, not caring to close his shutters or lock his door, pressing his head between his hands and moaning, till the cold grasped him and told him that his fire was grey. (Ch.X)

Not often did George Eliot attain such stark concreteness and force of the unerring word. Silas's color-drained world con- trasts with the church-going scene immediately following:

"the church was fuller than all through the rest of the year, with red faces among the abundant dark-green boughs. . . ."

Mrs. Barbara Hardy has shown that "in George Eliot the scenic method is inseparable from the habit of metaphor. The interplay between scene and image fixes a symbolic frame around the scene.

. .

."7 Christmas Day in Raveloe offers a wealth of confirmatory example.

The Casses' New Year's Eve dance (Ch.XI) is the pivotal point in the unfolding of the relation between community and non-community in the story. The zest and warmth of the col- lective occasion are tinglingly felt in the writing. George

Eliot holds a sensitive balance between her evocation of the choric whole, the total company linked as a community de- spite distinctions of social grading, and that of individual- ized figures (of whom Nancy and Priscilla Lammeter are the most vivid). The fellowship represented at the dance is exclusive: it is the occasion for "all the society of Raveloe and Tarley," not for all and sundry. But the "privileged villagers" who are admitted, like Macey and Ben Winthrop, are granted full and salted commentary on the doings of their betters. Their presence does not let us forget the wider popular community in whose name they speak.

The "legendary" element that enters deeply into the struc- ture of Silas Marner is most evident in the narration of

7The Novels of George Eliot, London, 1959, p. 200.

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

722 S I L A S M A R N E R

Silas's finding of the child on his cottage hearth (Ch.XII).

The role of chance, obvious and considerable, doesn't disturb: it confirms the legendary mood. The mother, giving way to the effects of her drug, collapses within a child's toddling distance (through snow) of Marner's cottage door. The door of the cottage is open (at the very moment Marner is hold- ing it ajar, caught in one of his cataleptic fits) so that the child can set out to catch "the bright living thing"-the light thrown across the darkened snow from the cottage fire. The child enters the cottage without Marner's being aware of it.

Recovering from his trance he goes back to his fireside: to his blurred vision, it seemed as if there were gold on the floor in front of the hearth. Gold!-his own gold brought back to him as mysteriously as it had been taken away! The heap of gold seemed to glow and get larger beneath his agitated gaze.

Not until he touches the gold does he encounter "soft warm curls" instead of "the hard coin with the familiar resisting outline." Later, when he first takes the child on his lap, he experiences an "emotion mysterious to himself, at something unknown dawning on his life." And instead of his being reduced to the world of objects, of being thingified, his chief fetish is itself made flesh:

Thought and feeling were so confused within him, that if he had tried to give them utterance, he could only have said that the child was come instead of the gold-that the gold had turned into the child" (Ch.XIV, my emphasis).

Up to the point of the child's discovery the narrative has much in common with the pastoral romance of a lost child and foster-father such as Shakespeare drew upon for The

Winter's Tale. There are some striking parallels. The asso- ciation of the discovered child with gold, and the fairy-tale coloring, occurs in The Winter's Tale. Having found the child and "bundle" left on the wild Bohemian shore by

Antigonus, the shepherd says to his son:

Now bless thyself: thou mettest with things dying,

I with things new-born. Here's a sight for thee: look thee, a bearing-cloth for a squire's child! Look thee here: take up, take up, boy; open't. So, let's see. It was told me I should be rich by the fairies: this is some changeling. Open't: what's within, boy?

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I AN MILNER 723

And the son replies:

You're a made old man: if the sins of your youth are forgiven you, you're well to live. Gold! all gold.

The old shepherd brings up the foundling as his daughter

Perdita. "Time, the Chorus" announces that sixteen years are to be passed over, bringing on the climax of the love and recognition scenes in which Florizel claims Perdita as wife and Perdita is revealed as the daughter of Leontes and

Hermione. Part II of Silas Marner opens with the sentence:

"It was a bright autumn Sunday, sixteen years after Silas

Marner had found his treasure on the hearth" (Ch.XVI).

Both the period and the structural function of the time ele- ment correspond exactly. Eppie, brought up by Silas as his own daughter, is found to be "a squire's child" (though she rejects her natural father). And she pledges herself to marry not a scion of the gentry but a workingman. The common elements are obvious. But the difference of denouement, de- termined by Eppie's acquired bond of kinship with working folk, is the essence of the tale.

There is also a difference of moral atmosphere. While

The Winter's Tale treats the incident as something out of an old ballad, George Eliot makes strong play with the nu- minous quality of Silas's experience. Telling Dolly Winthrop of the event Silas says: "Yes-the door was open. The money's gone I don't know where, and this is come from I don't know where" (Ch.XIV). Later, reflecting on his experience, he thinks of Eppie in terms of: "this young life that had been sent to him out of the darkness into which his gold had departed" (Ch.XVI). The "sent to him" links up with that first confused "feeling" he had had immediately after his discovery: "that this child was somehow a message come to him from that far-off life: it stirred fibres that had never been moved in Raveloe-old quiverings of tenderness-old impressions of awe at the presentiment of some Power pre- siding over his life .. ." (Ch.XII).

More than once Dolly Winthrop interprets the mystery as the natural working of the will of "Them as was at the making of us." And in the end Silas settles for a slightly troubled deism: " 'That drawing o' the lots is dark: but the child was sent to me: there's dealings with us-there's dealings'"

(Ch.XVI).

The drama of Marner's re-humanization is expressed in a

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

724 SILAS MARNER more realistic vein that contrasts significantly with the legendary and numinous atmosphere of his earlier alienation.

The shadowy, somewhat depersonalized Marner of Part I gradually acquires a voice and gestures of his own. His first tentative steps in parenthood are rendered with a moving simplicity, enlivened with a quiet humour which skirts senti- mentalization. The sense of an awakened Marner, of a man who has laid hold on life again, is strong in the little scene in which he defies Mrs. Kimble, the voice of respectable society, to take the child away:

"No-no-I can't part with it, I can't let it go," said Silas, abruptly. "It's come to me-I've a right to keep it." The proposition to take the child from him had come to Silas quite unexpectedly, and his speech, uttered under a strong sudden impulse, was almost like a revelation to himself: a minute before, he had no distinct intention about the child (Ch.XIII, my em- phasis).

The dialogue scenes in which Dolly Winthrop discourses on the whole right and duty of parents have a vitality and clarity of rendering which, if due primarily to her superlatively expressed vis animae, also show Marner in sharper profile.

Marner's recovery of his humanity emerges partly from the uncommented narrative of his growing care and affection for Eppie. It is also pointed up in the authorial commentary, not generalizing and didactic but expository: "Unlike the gold which needed nothing, and must be worshipped in close- locked solitude-which was hidden away from the daylight, was deaf to the song of birds, and started to no human tones-

Eppie was a creature of endless claims and ever-growing desired, seeking and loving sunshine, and living sounds, and living movements . . ." (Ch.XIV). Marner slowly comes to break out of the "ever-repeated circle" in which his thoughts had been trapped by his gold: "his soul, long stupefied in a cold narrow prison, was unfolding too, and trembling grad- ually into full consciousness' (Ch.XIV). The extent of the change in Silas is indicated in a passage at the close of Part I;

Wordsworthian in moral tone, it has a concrete simplicity of utterance and a natural vein of feeling that George Eliot rarely achieved:

No child was afraid of approaching Silas when

Eppie was near him: there was no repulsion around

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IAN MILNER 725 him now, either for young or old; for the little child had come to link him once more with the whole world.

There was love between him and the child that blent them into one, and there was love between the child and the world-from men and women with parental looks and tones, to the red lady-birds and the round pebbles (Ch.XIV).

Marner's loss and recovery of his humanity forms the major part of the novel's two-fold theme. It is developed by the skilful use of several mutually sustaining modes of presenta- tion. In the end the reader feels strongly that a warped and deadened personality has come alive and whole under "the remedial influences of pure, natural human relations."

* * *

The secondary theme in the double structure of Silas Marner is the conflict of contrasted moral values and of social planes in which those values respectively inhere. The confrontation, considering the novel's limited span, is worked out with a sure sense of dramatic gradation and tragic irony to a finely staged catastrophe. Godfrey and Silas are fatal opposites brought into a fatal conjunction. The thematic development of Marner's loss and recovery of his humanity is counter- pointed with the stages of Cass's moral deception and defeat.

The death of Godfrey's first wife (long willed by him) ironi- cally brings "salvation" to himself (he can marry Nancy

Lammeter) and to Silas (the finding of Eppie). Godfrey's marriage to Nancy, though it offers some happiness, is child- less: unblessed according to the tale's simple symbolism.

Eppie, the image of life's renewal, brings Silas back his lost humanity: "Eppie called him away from his weaving, and made him think all its pauses a holiday, reawakening his senses with her fresh life, even to the old winter-flies that came crawling forth in the early spring sunshine, and warm- ing him into joy because she had joy" (Ch.XIV).

The very discovery of the child sets off contrasted reactions.

Godfrey, when he first comes to Marner's cottage to see his daughter, feels "a conflict of regret and joy, that the pulse of that little heart had no response for the half-jealous yearn- ing in his own . . ." (Ch.XIII). He assumes Marner will hand the child over to the parish. "Who says so?" said Marner, sharply. "Will they make me take her?" The impulsive, pos- sessive love of the stranger lights up the self-divided cal-

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

726 S I L A S M A R N E R culatingness of the father, intent only upon a convenient dis- posal of the child and of his conscience:

"Poor little thing !" said Godfrey. "Let me give some- thing towards finding it clothes." He had put his hand in his pocket and found half-a-guinea, and, thrusting it into Silas's hand, he hurried out of the cottage . . .

(Ch.XIII).

Godfrey's half-guinea salve meets with a further challeng- ing contrast in the person of Dolly Winthrop. It is she whose immediately offered help in caring for the "tramp's child"

(as good society has it) Marner appreciates most. When he shows her the half-guinea she replies: "'Eh, Master Marner... there's no call to buy, no more nor a pair o' shoes; for I've got the little petticoats as Aaron wore five years ago, and it's ill like grass i' May, bless it-that it will'" (Ch.XIV). Dolly, the wife of Ben Winthrop the wheelwright, is finely indi- vidualized, above all by her speech, which in its natural run- ning on, its energy and liveliness, its homespun but never banal simplicity, is matched only by Mrs. Poyser's. Dolly has a Shakespearean largeness of stature, a rounded substantiality and rootedness in the earth. She is a genuine folk-figure, an image of the people's reserves of instinctive sympathy and care for the fellow-needy, practical know-how, forthrightness, resourcefulness, and good humor. She is the one person to whom Silas can unburden his doubts as to the drawing of lots that drove him into the wilderness. Dolly's faith that "Them as was at the making on us. .. knows better and has a better will" is in the last resort unshakable. But when she speaks of it the achieved control of tone and Shakespeare-like concrete- ness of language are evident:

And that's all as ever I can be sure on, and every- thing else is a big puzzle to me when I think on it. For there was the fever come and took off them as were full-growed, and left the helpless children; and there's the breaking o' limbs; and them as'ud do right and be sober have to suffer by them as are contrairy-eh, there's trouble i' this world, and there's things as we can niver make out the rights on. (Ch.XVI)

Dolly Winthrop, the wife of a working-man, complements

Marner, the weaver, in his function of creating the popular scale of values in the tale. Their friendly association at the

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

IAN M ILNER 727 outset in the bringing up of Eppie, their growing understand- ing of each other, are sealed by Eppie's marriage to Dolly's son Aaron.

The conflict of opposed values that has been growing throughout the story comes to a head in the final challenge- and-response scene between Godfrey and Nancy Cass and

Silas and Eppie (Ch.XIX). As in the encounter between Adam

Bede and Arthur Donnithorne the class gap between the pairs is brought out emphatically and in shrewdly varied ways.

Silas is on the defensive from the start: "always ill at ease when he was being spoken to by 'betters'" and answering

Godfrey "with some constraint." When Godfrey remarks that

Silas's gold (recovered with the finding of Dunstan Cass's body in the Stone-pit) won't go far, even to maintain only himself, Silas is "unaffected" by the rich man's argument:

"We shall do very well-Eppie and me 'ull do well enough.

There's few working-folks have got so much laid by as that.

I don't know what it is to gentlefolks, but I look upon it as a deal-almost too much.

. .

." From then on the scene has a spiralling tension, finely controlled as it mounts to the de- nouement. Godfrey pursues his gentlemanly line of the parent who, wishing to make amends, is bent merely on ensuring

Eppie's welfare: "making a lady of her." When Eppie re- sponds that she doesn't wish to be a lady (though dropping a curtsy respectfully) Godfrey gets assertive: "It's my duty,

Marner, to own Eppie as my child, and provide for her." He warns that otherwise Eppie "may marry some low working- man," and accuses Silas: "You're putting yourself in the way of her welfare." And Silas yields, after a struggle: "Speak to the child. I'll hinder nothing." There is a touch of classical tragic irony in Nancy and Godfrey's ready assumption, at this point, that their mission has succeeded:

"My dear, you'll be a treasure to me," said Nancy, in her gentle voice. "We shall want for nothing when we have our daughter."

It is Eppie who now stands at the center of the stage (the scene, like others of George Eliot's best, is as immediate and direct in its interchanges as a play). But she "did not come forward and curtsy, as she had done before. She held Silas's hand in hers, and grasped it firmly-it was a weaver's hand, with a palm and finger-tips that were sensitive to such pres- sure-while she spoke with colder decision than before":

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

728 S I L A S M A R N E R

"'Thank you, ma'am-thank you, sir, for your offers- they're very great, and far above my wish. For I should have no delight i' life any more if I was forced to go away from my father, and knew he was sitting at home, a-thinking of me and feeling lone. .. .' " When Nancy tries once more ("a duty you owe to your lawful father") Eppie brings the moral drama to a full close: "'I can't feel as I've got any father but one... I wasn't brought up to be a lady, and I can't turn my mind to it. I like the working-folks, and their victuals, and their ways. And,' she ended passionately, while the tears fell, 'I'm promised to marry a working-man, as '11 live with father, and help me to take care of him.'"

The dramatic surprise is well brought off, without histrio- nics. The social gap, and the habits of speech and behavior on each side of the gap (Eppie's curtsies and final "ma'am" and "sir"; Godfrey's recourse to moral principles to bolster his commandeering: ".. . it's my duty to insist on taking care of my own daughter") are finely caught. As in Adam Bede the clash of moral values is worked out and finally resolved within a specific class-differentiated context. Godfrey's natural assumption that his daughter should not marry "some low working-man" falls to pieces in face of Eppie's declaration.

The light of human charity comes from Silas Marner's hearth

-the "bright gleam" that fetched the child "in over the snow, like as if it had been a little starved robin," as Dolly Winthrop put it. It is the grasp of a weaver's hand that sustains Eppie when making her final act of commitment to "the working- folks ... and their ways."

The secondary theme of conflicting values adds a dimen- sion to the first. The "remedial influences of pure, natural human relations" operate within a conditioning social frame- work. Marner's alienation from himself and his fellow-man is healed by his uncalculating love for "a tramp's child." Godfrey

Cass disowns his own daughter. The revealing of Eppie as "a squire's child" immediately poses, in simple but dramatically clear-cut terms, the question of moral engagement so char- acteristic of the later novels. Eppie's commitment to the code of working-folk is the confirming counterpart of Marner's regaining of human lineaments. There is the wider implication, to be spelt out in the more complex crisis of Esther Lyon, that some such commitment is the necessary price of moral health.

The final quality of Sil(as Marner is other than "charming."8

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

I AN MILNER 729

The mark of man's inhumanity to man lies heavy across its early pages. Marner's cursing of his God, his destruction of himself as a human being, his abject despair, belong not to the pleasant illusion of fairy-tale but to the encounters of tragic moral drama. Silas Marner is one of the most effective renderings of the experience-so characteristically modern- of man's alienation. In the wide moral resonance of its double theme, and in its consummately controlled art, it merits a more substantial place in the critical estimate of George Eliot's work.

'After completion of my article I find that Dr. Leavis has somewhat revised his attitude. In a footnote, datemarked 1959, he states: "I think now that I have done less than justice to Silas Marner, and that my stresses on 'minor' and 'fairy-tales' are infelicitous." (The Great Tradi- tion, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin [Peregrine Books] 1962, p. 60 n.)

This content downloaded from 146.95.253.17 on Thu, 30 May 2013 11:19:29 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions