Calvaria Morphological Features: A Detailed Description

advertisement

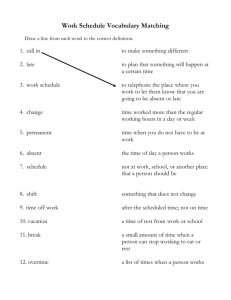

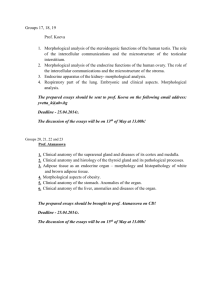

Appendix A: Morphological features description Appendix A: Morphological features description Calvaria #1: Outline of the calvaria in norma occipitalis (Fig. A.1). 3 states The cranium outline in norma occipitalis is widely used to characterise fossil specimens. For instance, the Neandertal calvaria shows a specific circular pattern (form “en bombe”, [1-3]) while the calvariae attributed to H. erectus s.l. generally present a triangular shape when viewed from behind [4]. Modern humans calvariae are generally described as being pentagonal [5, 6]. The three characters state definitions are based on the position of the largest cranial distance (euryon). 0.triangular 1.circular 2.pentagonal Figure A.1: Cranial outline in norma occipitalis with segments showing the largest cranial distance. From left to right: D2700 (cast, Natural History Museum, London (NHM), state 0), La Ferrassie 1 (original, Musée de l’Homme, Paris (MH), state 1) and Abri Pataud 1 (original, MH, state 2). #2: Frontal chord length (M29) relative to parietal chord length (M30) [7] (Fig. A.2). 3 states 0.frontal chord length is inferior to parietal chord length (M29/M30 ≤ 0.98) 1.frontal chord length is equal to parietal chord length (0.98 < M29/M30 < 1.02) 2.frontal chord length is superior to parietal chord length (M29/M30 ≥ 1.02) Appendix A: Morphological features description Figure A.2: M29 and M30 displayed on the La Ferrassie 1 Neandertal cranium. #3: Outline of the supra-orbital region in norma facialis. 2 states 0.anterior border of the supra-orbital region is strait 1.anterior border of the supra-orbital region is convex The supra-orbital region is composed of several complex morphological structures Schwalbe [8] defined two main components: the arcus supraciliaris and the arcus supraorbitalis which can be merged or separated by the sulcus supraorbitalis. Cunningham [9] identified the trigonum supraorbitale and classified the variation of the supra-orbital region in four main morphological types. Santa Luca [10] described the median part of the supra-orbital region by the presence of a torus glabellaris. In 1984, Spitery characterised the supra-orbital region as being composed of a medial structure (glabella) and two lateral supar-orbital tori. His description of the supra-orbital torus is linked to the definition of the sulcus supraorbitalis which originates from the frontal notch and develops obliquely on the antero-superior surface of the supra-orbital region. These features have been variably used to describe the range of morphologies observed in the hominin fossil record [1215]. #4: Supra-orbital region, presence of a sulcus supraorbitalis (Fig. A.3). 3 states According to some authors [3, 9, 16], the three structures of the supra-orbital region (arcus supraorbitalis, arcus supraciliaris and trigonum supraorbitale) are always merged in classic Neandertals, while they are clearly individualized in modern humans and a clear sulcus supraorbitalis separates the arcus supraorbitalis and arcus supraciliaris. 0.presence of a sulcus supraorbitalis 1.presence of an incomplete sulcus supraorbitalis; the supra-orbital trigon is merged posteriorly with the arcus superciliaris 2.absence of a sulcus supraorbitalis Appendix A: Morphological features description Figure A.3: Components of the supra-orbital region. G: glabella; Ar. S: arcus supraciliaris; Sul S: sulcus supraorbitalis; Ar. O: arcus supraorbitalis; T: trigonum supraorbitale. Abri Pataud 1 (state 0). #5: Projection of the supra-orbital region. 3 states 0.the supra-orbital region is not projecting 1.the arcus superciliaris only is projecting 2.the supra-orbital region is projecting #6: Post-orbital constriction (Fig. A.4). 3 states The post-orbital constriction is sometimes used to define H. erectus s.l. [17]. Here, we estimate the post-orbital constriction thanks to the post-orbital constriction index (Icp) defined as follows: Icp=M9/M43. M9 corresponds to the minimal length of the frontal and M43 to the total length of the post-orbital region [7]. 0.important post-orbital constriction (Icp < 0.75) 1.weak post-orbital constriction (0.75 ≥ Icp ≥ 0.85) 2.absence of post-orbital constriction (Icp > 0.85) Figure A.4: The M9 and M43 distances are portrayed on Cro-Magnon I (Original, MH) cranium. #7: Outline of the supra-orbital region in norma verticalis (Fig. A.5). 3 states Appendix A: Morphological features description 0.supra-orbital region is medially concave (glabella) 1.supra-orbital region is straight 2.supra-orbital region is convex Figure A.5: Outline of the supra-orbital region in norma verticalis. From left to right: Petralona (Original, Aristotle University, Thessaloniki, state 0), ZH XII (Cast, Senkenberg Forschungsinstitut und Naturmusem, Frankfurt (SFN), state 1) and Spy 1 (Original, Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique, Bruxelles (IRSBN), state 2). #8: sulcus postorbitalis. 3 states Posteriorly to the supra-orbital region a post-orbital sulcus may be observed on most fossil specimens. The sulcus postorbitalis may be continuous, extending on the whole supra-orbital region, or reduced to the medial part of the supra-orbital region (glabella). The presence of a sulcus postorbitalis is usually considered to be specific to H. erectus s.l. even though the definition of the character remains unclear [18]. Neandertals also present a more or less continuous sulcus [3]. 0.sulcus postorbitalis absent 1.sulcus postorbitalis medially present (glabella) 2.sulcus postorbitalis present and continuous #9: Tuber frontale. 3 states According to Stringer et al. [19], a tuber frontale associated to a high and rounded frontal bone may be considered as a modern human derived feature. Modern humans’ tuber frontale are described as being caused by the antero-posterior extension of the brain during growth by Lieberman [20]. Such a character is difficult to observe due to its large morphological variation among the Pleistocene hominin fossils [12, 21]. Here we are using three states to depict the tuber frontale morphological variation. 0.absent 1.present and medially shifted 2.present well-defined Appendix A: Morphological features description #10: Antero-posterior convexity of the frontal (Fig. A.6). 3 states The antero-posterior convexity of the frontal is estimated using the Icf index defined as follows: M29*100/M26. M29 is the nasion-bragema chord and M26 is the nasio-bregma arc [7]. 0.weak (Ifc ≥ 95) 1.intermediate (95 > Icf ≥ 90) 2.important (Ifc <90) Figure A.6: Antero-posterior convexity of the frontal. From left to right: ZH III (Cast, SFN, state 1) and Abri Pataud 1 (state 2). #11: Linea temporalis development on the frontal. 3 states 0.absent 1.present, unique 2.present, double #12: Medio-sagittal supra-glabellar tubercle. 2 states Zeitoun [15] noticed that the frontal of H. neanderthalensis often presents an ovoid tubercle posterior to the supra-orbital torus. 0.absent 1.present Fossil hominins often show numerous superstructures on their calvaria. Some of these, especially the ones located on the frontal and parietal, are considered to be derived features of H. erectus s.s. [18, 22-25]. We are aware that some of the calvaria superstructures may be developmentally correlated [25, 26]. In order to better account for the existing morphological variation in the fossil record, the Appendix A: Morphological features description sagittal keel on the frontal, the bregmatic eminence and the thickening of the superior part of the coronal sutures have been observed and coded separately. #13: Sagittal keel on the frontal. 2 states A thickening of the frontal bone in its medial part (on the metopic suture) is considered to be a H. erectus s.l. derived feature [17, 24] and more specifically of the Asian specimens [22, 25]. However, this inference has been questioned [12, 27], and particularly Bräuer and Mbua [28]classify the character as a shared primitive feature. 0.absent 1.present #14: Bregmatic eminence. 2 states 0.absent 1.present #15: Thickening of the superior part of the coronal sutures. 2 states 0.absent 1.present #16: Sagittal keel on the bregma-lambda arc. 2 states The sagittal keel is a thickening of the bone at the level of the bi-parietal suture. 0.absent 1.present #17: Parasagitall hollowing on both sides of the parietal suture. 2 states 0.absent 1.present #18: Pre-lambdatic hollowing on the bregma-lambda arc. 2 states A pre-lambdatic hollowing on the bregma-lambda arc was described by Weidenreich [29] on the Sinanthropus specimens. Appendix A: Morphological features description 0.absent 1.present The configuration and position of the linea temporalis on the parietal is often used in the description of the fossils of the genus Homo [4, 15, 30, 31]. In order to better account for the morphological variation of this anatomical structure, we used two features. #19: Width of the band formed by the linea temporalis on the parietal. 3 states 0.absent 1.narrow (< 20mm) 2.wide (≥ 20mm) #20: Position of the superior linea temporalis on the parietal (Fig. A.7). 3 states We estimated the position of the linea temporalis on the parietal by measuring on the arc asterionbregma, the distance between the temporo-parietal suture and the superior temporal line (Dt) and the distance between the temporo-parietal suture and the bregma (Db), and computed the index Rlt=Dt/Db. This character is extremely variable in the studied fossil sample [21]. 0.high (Rlt > 0.55) 1.medial (0.54>Rlt > 0.46) 2.low (Rlt < 0.45) Figure A.7: Arcs temporoparietal suture – superior temporal line (Dt) and temporo-parietal suture – bregma (Db) on Abri Pataud 1. #21: Torus angularis parietalis (Fig. A.8). 2 states The torus angularis parietalis was first described by Weidenreich [29] as a rounded bulge on the parietal surface situated at the angle of the lambdoid and parieto-mastoid sutures. It is often Appendix A: Morphological features description considered as specific to H. erectus s.l. [17, 22]. It is however often absent from the African specimens [18, 25, 26]. 0.absent 1.present Figure A.8: Presence of a torus angularis parietalis. Sangiran 17 (Cast, Université de la Méditerranée, Marseille (UM)). #22: Tuber parietale (Fig. A.9). 3 states Krukoff [32] defined the tuber parietale as the exocranial point which constitutes the summit of a pyramid which base is formed by a triangle bregma – lambda – fronto-parietal (i.e. the parietum). When the tuber parietale are not well-defined, the parietum corresponds to the maximum curvature of the bone. Well-defined tuber parietale are specific to H. sapiens [4]. 0.absent, the parietum corresponds to the maximum curvature of the bone 1.presence of tuber parietale medially shifted on the parietal 2.presence of tuber parietale in a high position on the parietal Figure A.9: Triangle bregma – lambda – fronto-parietal defining the parietum. Abri Pataud 1. #23: Outline of the occipital in norma lateralis (Fig. A.10). 2 states Appendix A: Morphological features description Estimation of the curvature of the occipital bone is difficult to evaluate [2, 33]. A sharply angled occipital is sometimes considered as a specific feature of H. erectus s.l. [17, 25], while modern humans present a rounded occipital [2]. In Neandertals the presence of an occipital bun might obscur the observation of this morphological feature; however, they generally show an angled occipital [2, 3]. 0.rounded profile 1.sharply angled Figure A.10: Outline of the occipital in norma lateralis. From left to right: Qafzeh 9 (Cast, UM, rounded profile, state 0); Sangiran 17, (sharply angled, state 1). #24: Outline of the planum occipitale in norma lateralis. 2 states The planum occipitale is defined by the position of the inion which is located at the junction of the superior nuchal lines and the medio-sagitall plane (i.e. exactly on the tuberculum linearum) [7, 23, 34]. A strong convexity of the planum occipitale might be more specific to H. neanderthalensis [35]; this might be linked to the presence of an occipital bun (see #26). 0.no convexity 1.convexity #25: Relative development of the planum nucale (PN) and the planum occipitale (PO). 2 states A shorter planum occipitale in relation to the planum nucale can be observed on the Asian H. erectus specimens. This morphology does not generally occur in the African H. erectus specimens and is absent in H. sapiens and H. neanderthalensis [25, 26]. 0.PN≥PO 1.PN<PO #26: Occipital bun. 2 states Trinkaus and Lemay [36] defined this anatomical structure as being “a posterior projection of the occipital squama which is evenly rounded in norma lateralis and slightly compressed in a craniocaudal direction” (p. 27). Boule [1] was the first author to describe the structure on La Chapelle-aux-Saints Appendix A: Morphological features description and the occipital bun is generally considered as being a Neandertal synapomorphy [37, 38]. The occipital bun can however be observed in some anatomically modern humans [36, 39, 40]. 0.absent 1.present #27: Opisthocranion relative position in relation to inion. 2 states The inion and the opisthocranion are generally located at the same position on H. erectus s.l. specimens. However, it is not always the case and this morphology is not considered to be specific to H. erectus s.l. populations [22, 25]. According to Hublin [23], in early Homo specimens, the opsithocranion is situated on the highest point of the occipital torus, i.e. just above the inion. In this case we considered that the opisthocranion and inion were located at the same position. 0.same position 1.different position #28: Processus retromastoideus. 2 states The processus retromastoideus is located halfway between the inion and the processus mastoidus, and is the insertion for the m. obliquus capiti superior. More precisely, the processus retromastoideus is a protuberance on the planum nucale at the meeting point of the occipital torus and the inferior nuchal lines [10]. Weidenreich observed it on the Ngandong specimens [41]. 0.absent 1.present #29: Outline of the planum occipitale in norma occipitalis (Fig. A.11). 3 states A triangular outline on the superior part of the occipital bone is often considered as characteristic of early Homo specimens, especially H. erectus s.l. [13], while modern humans and Neandertals show a more rounded or pentagonal outline. 0.triangular 1.circular 2.penatgonal Appendix A: Morphological features description Figure A.11: Outline of the planum occipitale in norma occipitalis. From left to right: Sangiran 4 (Original, SFN; triangular, state 0); La Ferrassie 1, (rounded, state 1); Abri Pataud 1 (pentagonal, state 2). The suprainiac fossa is considered as a specific Neandertal character [19, 35, 42]. It is located above the occipital torus and can occasionally be observed on modern human specimens [35]. #30: Suprainiac fossa (Fig. A12). 3 states 0.absent 1.hollowing, weakly-delineated 2.present #31: Configuration of the lateral edges of the suprainiac fossa (Fig. A.12). 3 states 0.absent 1.convergent upward 2.parallel or arched Figure A.12: Suprainiac fossa. From left to right: Swanscombe (Original, NHM), hollowing weakly-delineated (#30, state 1) with edges converging upward (#31, state 2); Gibraltar 1 (Original, NHM), present (#30, state 2) with arched edges (#31, state 2). The torus occipitalis transversus is regularly used in the definition of h. erectus s.l. [17, 23, 25, 26, 43], although its morphological definition is sometimes unclear. Stringer [26: 56] refers to a “strong torus Appendix A: Morphological features description occipitalis”, Rightmire [17: 189] notes that the “morphology of the transverse torus of the occiput is distinctive, as noted by Wood (1984) and others, although there is a good deal of variation.” Hublin’s definition of the torus in H. erectus is clearer [23: 180]: “A strong occipital torus develops between the asterion, joining the torus angularis, the supramastoid crests and the occipito-mastoid crests. It is a thickening of the external table of the occipital between the superior nuchal lines and the suprema nuchal lines forming a sulcus supratoralis. Its maximum development is in the median area, above the tuberculum linearum”, as for Neandertals [35: 69]: “Comparé à celui des Homo erectus asiatiques, ce torus occipital est faiblement développé, si l’on tient compte des mesures d’épaisseur (Hublin, 1978). (…) Latéralement il s’étend rarement au-delà de l’insertion des m. semispinalis capitis (Spy 2). (…) Dans sa partie médiane, sous la fosse sus-iniaque, le torus est lui-même déprimé et ses points de développement maximal sont situés latéralement. Ainsi en vue inférieure le torus présente une saillie bilatérale et non une saillie maximale médiane comme c’est habituellement le cas”. The torus occipitalis transversus is generally circumscribed by a sulcus supratoralis. It is not always present and its morphology differs widely. According to Condemi [3] the sulcus supratoralis delineates the occipital bun in Neandertals and is clearly defined in its lateral part while being less marked in its medial part. We used three different morphological features in order to better describe the morphological variation of the torus occipitalis transversus. #32: Sulcus supratoralis development. 3 states 0.absent 1.hollowing 2.present #33: Torus occipitalis transversus development (Fig. A.13). 3 states 0.absent 1.the torus is present and medially protruding 2.the torus is present and bilaterally protruding Figure A.13: Torus occipitalis transversus. From left to right: Sangiran 4, medially protruding torus (state 1); La Ferrassie 1, bilaterally protruding torus (state 2). #34: Torus occipitalis transversus, form in norma occipitalis. 3 states Appendix A: Morphological features description Among classic Neandertals, the torus occipitalis transversus is usually rectilinear when observed in norma occipitalis [3]. The torus form is usually more variable in older hominins. 0.absent 1.the torus is present and rectilinear 2.the torus is present and convex Hauser and De Stefano [44] defined the protuberantia occipitalis externa (external occipital protuberance) as formed by the convergence of the highest nuchal lines superiorly, and of the superior nuchal lines inferiorly. The absence of the occipital protuberance is considered by Hublin [34, 35] as an archaic feature which can be observed on most Neandertals. Modern humans generally present such a protuberance. The tuberculum linearum is the meeting point of the superior nuchal lines and forms a weakly-defined triangular tubercle. The presence of a tuberculum linearum is variable but it is not linked to the external occipital protuberance (Fig. A.14). #35: Protuberantia occipitalis externa (external occipital protuberance, Fig. A.14). 2 states 0.absent 1.present #36: Tuberculum linearum (Fig. A.14). 2 states 0.absent 1.present Figure A.14: Protuberantia occipitalis externa and tuberculum linearum. From left to right: La Ferrassie 1, absence of a protuberantia occipitalis externa (#35, state 0) and of a tuberculum linearum (#36, state 0); Sangiran 4, absence of a protuberantia occipitalis externa (#35, state 0), presence of tuberculum linearum (#36, state 1); Abri Pataud 1, presence of a protuberantia occipitalis externa (#35, state 1), absence of a tuberculum linearum (#36, state 1). Appendix A: Morphological features description The external occipital crest is generally poorly defined in classic Neandertals; its expression is variable among European Middle Pleistocene hominins as it is the case for modern humans [45]. The relative development of the posterior and anterior parts of the crest separated by the inferior nuchal line is often unequal. Classic Neandertals usually present a dissymmetry regarding the development of the posterior and anterior parts of the external occipital crest [3]. #37: External occipital crest development. 3 states 0.absent 1.external occipital crest present posteriorly 2.external occipital crest present #38: Aligned posterior and anterior parts of the external occipital crest. 2 states 0.yes 1.no #39: Temporal squama height (Fig. A.15). 2 states Vallois [46] first described a low temporal squama in Neandertals. This observation was later made on numerous older specimens, notably on Homo erectus s.l. fossils. This feature is often seen has being characteristic of the most ancient hominins [22, 23, 25, 47]. Caparros [12] noted that a low temporal squama could also be observed in some Anatomically Modern Humans (AMHs). In order to evaluate the height of the temporal squama, we used the method first defined by Schultz [48] and then used by Vallois [46] in the study of the temporal bone La Quina H27. For a specimen orientated in the Frankfurt plane, the maximal height (H) of the squama from the auriculae is divided by the maximal width of the squama (L) to calculate the index Iet, i.e. Iet=(Hx100)/L (Fig. A.15) 0.low temporal squama (Iet≤60) 1.high temporal squama (Iet>60) Appendix A: Morphological features description Figure A.15: Description of the index Iet on Broken Hill (Original, NHM). 1: Frankfurt plane; 2: auriculae; H: squama maximum height; L: squama maximum width. The outline of the temporal squama is generally more curved in AMHs than in older hominins or in Neandertals [46]. However, the latter is not always true and some Neandertals show a curved outline of the temporal squama [47]. For Homo erectus specimens the temporal squama is often described as being low with a triangular outline [17, 29, 49]. #40: Outline of the anterior border of the temporal squama. 2 states 0.curved or sinuous 1.rectilinear #41: Outline of the superior border of the temporal squama. 2 states 0.curved or sinuous 1.rectilinear A well-developed crista supramastoidea together with a tuberculum supramastoideum anterius can be observed in Neandertal fossils as well as Middle and Early Pleistocene hominins [22, 46, 47]. #42: Development of the crista supramastoidea at the porion. 3 states 0.absent 1.weakly-developed 2.marked Santa Luca [10] observed that the crista supramastoidea and the processus zygomaticus ossis temporalis were often lined up among the Ngandong fossils. Appendix A: Morphological features description #43: Relative orientation of the crista supramastoidea and the processus zygomaticus ossis temporalis (zygomatic process of the temporal bone) (Fig. A. 16). 2 states 0.crista supramastoidea and the processus zygomaticus ossis temporalis are not lined up 1.crista supramastoidea and the processus zygomaticus ossis temporalis are lined up Figure A.16: Relative orientation of the crista supramastoidea and the processus zygomaticus ossis temporalis. From left to right: La Ferrassie 1, crista supramastoidea and the processus zygomaticus ossis temporalis are not lined up (state 0); Broken Hill, crista supramastoidea and the processus zygomaticus ossis temporalis are lined up (state 1). Posteriorly to the crista supramastoidea, a tubercle (tuberculum supramastoideum anterius), which development stops abruptly at the parieto-temporal suture, is sometimes observed [50]. #44: Tuberculum supramastoideum anterius. 2 states 0.absent 1.present Weidenreich [29] observed the presence of a supramastoid groove between the crista supramastoidea and the crista mastoidea on the Sinanthropus fossils while this groove was absent from the Ngandong specimens. For Stringer [25], the crista supramastoidea and the crista mastoidea are joined in the Asians Homo erectus #45: Supramastoid groove between the crista supramastoidea and the crista mastoidea. 3 states 0.absent 1.present but closed anteriorly 2.present Appendix A: Morphological features description The auditory meatus is generally elliptic in AMHs. According to Elyaqtine [49], the hominins of the Neandertal lineage evolved from an elliptic form to a more circular form that can be observed in classic Neandertals. #46: Form of the external auditory meatus. 2 states 0.the auditory meatus is circular 1.the auditory meatus is elliptic Many authors consider that the position of the auditory meatus is particular in Neandertals where it occupies a « high » position: it is situated above the glenoid cavity and thus, is lined up with the processus zygomaticus temporalis [13, 46, 47, 49]. #47: Position of the auditory meatus in relation to the processus zygomaticus temporalis (Fig. A.17). 3 states 0.the auditory meatus is below the zygomatic process 1.the auditory meatus is in an intermediate position in relation to the zygomatic process 2.the auditory meatus is lined up with the zygomatic process Figure A.17: Position of the auditory meatus in relation to the processus zygomaticus temporalis. From left to right: Gibraltar 1, below (state 01); Petralona, intermediate position (state 1); La Ferrassie 1, lined up (state 2). The processus mastoidus (mastoid process) is generally weakly-developed in Homo erectus s.l. and Homo neanderthalensis [46, 47, 51, 52]. However, this feature is variable, even among Homo erectus s.l.. Furthermore, a weakly-developed mastoid process can also be observed in Early Pleistocene specimens [23]. We coded the downward development of the processus mastoidus in relation to the petrous part of the temporal bone in norma lateralis. The presence of a tubercle (tuberculum mastoideum anterior) on the anterior border of the mastoid process behind the external auditory meatus can be considered as a Neandertal trait [37, 47, 49]. #48: Tuberculum mastoideum anterior. 2 states Appendix A: Morphological features description 0.absent 1.present #49: Downward development of the processus mastoidus in relation to the petrous part of the temporal bone. 2 states 0.weak 1.strong Hublin [50] described the juxtamastoid ridge as forming the medial edge of the digastric groove. It is generally positioned on the occipitomastoid suture. The juxamastoid ridge is especially protruding in Neandertals but it can occasionally be observed in AMHs [35]. For some authors, a juxtamastoid ridge which is more developed downward than the processus mastoidus should be considered as a Neandertal trait [47, 49]. #50: Juxtamastoid ridge development in relation to the processus mastoidus. 3 states 0.less developed 1.as developed 2.more developed Vallois [46] described the presence of a bony bridge over the digastric groove, separating the posterior and the anterior part of the digastric groove, as being a Neandertal trait. However, this morphology has been noted in some specimens from Zhoukoudian and Sangiran [47]. Actually, the digastric groove morphology may be variable in AMHs, Neandertals or Asians Homo erectus s.l. [29, 47]. #51: Presence of a bony bridge over the anterior part of the digastric groove. 2 states 0.absent 1.present The occipitomastoid suture of the Sinanthropus hominins displays a crest formed by the fusion of the linea musculus obliquus capitis superior and the juxtamastoid groove [17, 29]. This structure has also been observed in most of the other Asian Homo erectus fossils [23]. #52: crista occipitomastoidea (occipitomastoid crest). 2 states Appendix A: Morphological features description 0.absent 1.present According to Condemi [47], the morphology of the glenoid cavity is one of the few traits that can be considered as proper to the Neandertals’ temporal: “La cavité est très étendue, large, peu profonde et mal délimitée avec vers l’avant un tubercule temporal (tuberculum articulare) peu saillant. Si la présence d’un tubercule zygomatique postérieure n’est pas propre aux Néandertaliens, en revanche, sa participation au versant postérieure de la cavité glénoïde ne se retrouve que sur ces fossiles würmiens.” [47: 51]. A narrow glenoid cavity in its medial part is considered to be more specific to the Homo erectus s.l. by Rightmire [17]. However, Hublin [23] advocated that the morphological variability of the glenoid cavity was too important and that one should consider with caution its taxonomic value. #53: Glenoid cavity depth in relation to the articular tubercle lowest point. 2 states 0.shallow (<0.9 mm) 1.deep (>0.9 mm) #54: petro-tympanic crest orientation in relation to the sagittal plane (Fig. A.18). 3 states 0.perpendicular 1.frontward 2.backward Figure A.18: Petro-tympanic crest orientation. From left to right: La Quina H5 (Original, MH), perpendicular (state 0); Abri Pataud 1, frontward (state 1); Sangiran 2 (Original, SFN), backward (state 2). Appendix A: Morphological features description According to Elyaqtine [49, 53], the articular tubercle is generally concave medio-laterally in Neandertals, while it is also convex antero-posteriorly in AMHs. Older hominins display more variability in the configuration of their articular tubercle. #55: Articular tubercle configuration (Fig. A.19). 3 states 0.the articular tubercle shows a pronounced medio-lateral concavity 1.the articular tubercle shows an antero-posterior convexity which can be associated with a medio-lateral concavity 2.the articular tubercle is concave medio-lateraly and vertical Figure A.19: Configuration of the articular tubercle. From left to right: Ceprano (Original, Soprintendenza Archeologia del Lazio, Rome), medio-lateral concavity (state 0); Sangiran 2, medio-lateral concavity (state 0); Abri Pataud 1, antero-posterior convexity (state 1); Ngandong 14 (Cast, SFN), medio-lateral concavity and vertical (state 2). On the inferior aspect of the zygomatic process, the glenoid cavity is delimited by two other tubercles: anteriorly, the tuberculum zygomaticum anterius, and posteriorly, the tuberculum zygomaticum posterius. Vallois [46] described the tuberculum zygomaticum anterius as being strongly pronounced and thick in Neandertals but much less protruding than in modern humans. Conversely, the tuberculum zygomaticum posterius is defined as being more protruding in Neandertals than in modern humans. While Vallois advocated that these morphologies were specific to Neandertals, Condemi [47] noted that a strong development of the tuberculum zygomaticum posterius can be seen in older fossils. #56: tuberculum zygomaticum anterius. 2 states 0.absent to weakly-pronounced 1.pronounced Appendix A: Morphological features description #57: tuberculum zygomaticum posterius. 2 states 0.absent to weakly-marked 1.marked In Neandertals and older hominins, the tuberculum zygomaticum posterius, when well-developed, may contribute significantly to the posterior wall of the glenoid cavity. This morphology does not usually occur in modern humans [22, 23, 25, 46, 47]. #58: Tympanal contribution to the posterior wall of the glenoid cavity (Fig. A.20). 2 states 0.tympanal contribution to the posterior wall of the glenoid cavity is relatively weak 1.tympanal contribution to the posterior wall of the glenoid cavity is important Figure A.20: Tympanal contribution to the posterior wall of the glenoid cavity. From left to right: La Ferrassie 1, state 0; La Quina H5, state 1. #59: Presence of a preglenoid tubercle. 2 states 0.absent 1.present Vallois [46] observed that in some Neandertals, the spina glenoidalis (glenoid spine) closes the glenoid cavity instead of the sphenoid spine. #60: Closing of the glenoid fossa. 2 states 0.the glenoid fossa is closed by the spina glenoidalis Appendix A: Morphological features description 1.the glenoid fossa is closed by the sphenoid spine Upper Face In the past, the general orbit form of Neandertals has often been described as being rounded, while AMHs’ orbits were often considered to be rectangular [1, 3, 54]. For Weidenreich [29], the Sinanthropus’ orbits are more triangular. However, some authors challenged these statements [55, 56] and emphasised the important morphological variability existing in orbital forms. In the present study, we chose to describe the orbital form using three criteria [57, 58] (Fig. A.21). #61: Form of the superior orbital rim (Fig. A.21). 3 states 0.the superior orbital rim is horizontal 1.inclined: the medial end of the superior orbital rim is slightly higher than the lateral end 2.strongly inclined: the medial end of the superior orbital rim is higher than the lateral end #62: Form of the supero-lateral orbital rim (Fig. A.21). 2 states 0.the supero-lateral orbital rim is forming a right angle or a slightly rounded right angle 1.the supero-lateral orbital rim is arched #63: Form of the inferior orbital rim (Fig. A.21). 3 states 0.the inferior orbital rim is horizontal 1.inclined: the medial end of the inferior orbital rim is slightly higher than the lateral end 2.strongly inclined: the medial end of the inferior orbital rim is higher than the lateral end Figure A.21: Description of the orbital form. From left to right: Gibraltar 1: #61: state 0, #62, state 0, #63 state 2; La Ferrassie 1: #61: state 1, #62, state 1, #63 state 2; Qafzeh 6 (Original, Institut de Paléontologie Humaine, Paris): 22 Appendix A: Morphological features description #61: state 2, #62, state 1, #63 state 2 The inter-orbital space is generally considered as being wider in fossil populations (to the exception of Homo habilis s.l.) and especially in Neandertals [1, 29, 59]. However, as also noted by Maureille [55], the ratio of the bi-orbital length to the inter-orbital length is not particularly different between hominin populations (Homo neanderthalensis, Homo erectus, archaic Homo sapiens) and current populations. #64: Inter-orbital space. 2 states 0.inter-orbital space is narrow (<29 mm) 1.inter-orbital space is wide (≥29 mm) Weidenreich [29] described the naso-frontal suture as being on the same plane as the frontomaxillary suture in Sinanthropus. For Maureille [55], the variation of this feature in current humans is extremely important. We coded this character following Liu et al. [58]. #65: Form of the naso-frontal and fronto-maxillary sutures (Fig. A22). 3 states 0.naso-frontal and fronto-maxillary sutures are in the same plane: horizontal 1.naso-frontal and fronto-maxillary sutures show a curved or inclined pattern 2.naso-frontal and fronto-maxillary sutures show a trapeziform pattern Fig. A.22: Form of the nasofrontal and fronto-maxillary sutures. From left to right: Guattari 1 (Original, Museo L. Pigorini, Rome), inclined sutures (state 1); La Chapelle-aux-Saints (Original, MH) inclined sutures (states 1); Cro-Magnon 1, trapeziform sutures (state 2). Franciscus [60] studied the configuration of the nasal floor and of the internal nasal aperture. He first described different merging patterns of the turbinal crest, spinal and lateral border. The important morphological variation of this feature did not allow him to identify an evolutionary related pattern. However, the nasal floor configuration seems to bear some phylogenetic information, since a bi-level nasal floor can be observed on a majority of Neandertals [2, 14, 60]. Furthermore, Vandermersch [2] noted this configuration on some North African Homo erectus. #66: Nasal margin configuration: relationships between the lateral, spinal and turbinal crests (Fig. A.23). 5 states 23 Appendix A: Morphological features description 0.the lateral, spinal and turbinal crests are not merged 1.the spinal and turbinal crests are merged 2.the lateral and spinal crests are merged 3.the lateral and turbinal crests are merged 4.the lateral, spinal and turbinal crests are merged #67: Configuration of the nasal floor (Fig. A.23). 3 states 0.sloped nasal floor 1.level nasal floor 2.bi-level nasal floor Figure A.23: Nasal aperture morphologies. From left to right: La Chapelle-aux-Saints and Gibraltar 1, merged lateral and spinal crests (#66, state 2), bi-level nasal floor (#67, state 2); Petralona, merged lateral, spinal and turbinal crests (#66, state 4), bi-level nasal floor (#67, state 2); Abri Pataud 1, merged turbinal and spinal crests (#67, state 1), level nasal floor (#67, state 1). The inferior margin of the nasal cavity shows a range of morphologies. We chose three states to characterize this feature [6]. According to Maureille [55], the presence of a pre-nasal fossa (i.e. gouttière prénasale) is extremely variable, and should not be considered as derived for any hominin population. It can be observed in some Neandertals as well as in some extant humans. #68: Form of the inferior margin of the nasal cavity (Fig. A.24). 3 states 0.sharp inferior margin 1.presence of a pre-nasal fossa 2.presence of a pre-nasal sulcus 24 Appendix A: Morphological features description Figure A.24: Form of the inferior margin of the nasal cavity. From left to right: Qafzeh 6, sharp inferior margin (state 0); Gibraltar 1, presence of a pre-nasal fossa (state 1); Broken Hill, presence of a pre-nasal sulcus (state 2). #69: Relative positions of the superior and inferior orbital rims in norma lateralis. 3 states 0.superior orbital rim is positioned anteriorly 1.superior and inferior orbital rims are levelled 2.superior orbital rim is positioned posteriorly A deep nasion in relation to glabella has been considered for many years as a specific character of Early Homo but also of Neandertals. Boule [1] used this feature in its facial definition of the Neandertal populations. Patte [56] noted that the Neandertal nasion is not situated in a hollowing but instead is in a high position on the supra-orbital torus. #70: Nasion relative depth compared to glabella in norma lateralis. 3 states 0.nasion is in a deep position under the glabella 1.nasion is in a shallow position under the glabella 2.nasion and glabella are positioned at the same level According to Weidenreich [29], the nasal bones of Sinanthropus are slightly concave. AMHs and Neandertals usually present a much more concave profile, although the current morphological variation in modern humans is large [55]. This concavity is difficult to observe. Therefore we chose to code the projection of the nasal bones in relation to the naso-frontal suture. #71: Nasal bones projection in relation to the naso-frontal suture. 2 states 0.nasal bones are weakly-projecting 1.nasal bones are strongly-projecting #72: Orientation of the lateral margins of the nasal cavity in norma lateralis. 2 states 25 Appendix A: Morphological features description 0.the lateral margins are sloping anteriorly 1.the lateral margins are vertical or concave #73: Position of the projection of the inferior part of the temporal process of the zygomatic (craniometric point zygotemporal inferior) on the nasal aperture in norma lateralis [61] (Fig. A.25). 3 states 0.low, the projection of the zygotemporal inferior is at the level of the inferior rim of the nasal aperture 1.median, the projection of the zygotemporal inferior is at the level of the inferior part of the nasal aperture 2.high, the projection of the zygotemporal inferior is at the level of the superior part of the nasal aperture Figure A.25: Projection of the inferior part of the temporal process of the zygomatic on the nasal aperture in norma lateralis. From left to right: SH5, low (state 0); Saccopastore 2, median (state 1); Abri Pataud 1, high (state 2). The morphology of the zygomatic was quantified by Maureille [55]. Caparros [12] described it as a discrete trait with two modalities (strongly angled zygomatic, discontinuous with the maxilla and incurved zygomatic). We believe that this dichotomy is not satisfying to describe the classic Neandertal zygomatic morphology [1, 3, 62]. Sergi [62] defined the pneumatised face of the Neandertals by underlying that the external surface of the zygomatic and the maxilla are continuous. For Sergi, it is the absence of concavity on the anterior surface of the maxilla as well as the absence of angle between the maxilla and the zygomatic that define the Neandertal peculiar morphology (see also [3]). Vandermeersch [2] made the zygomatic configuration one of the most important points of the diagnosis of Homo sapiens he proposed: the zygomatic is strongly angled between the body and the temporal process of the bone, and frontal and lateral faces can be defined. In her study of the Saccopastore fossils, Condemi [3] noted that their zygomatic presented somewhat an intermediary configuration between AMHs and Neandertals: the body of the zygomatic is curved in the horizontal plane and in the coronal plane. It is worth noting that using these definition,s we observed a strongly angled zygomatic in some Early Homo fossils. #74: Zygomatic orientation in relation to the maxilla (Fig. A.26). 3 states 26 Appendix A: Morphological features description 0.strongly angled zygomatic, discontinuous with maxilla and displaying distinctive frontal and lateral faces. 1.curved zygomatic in the horizontal and coronal planes 2.oblique zygomatic, continuous with maxilla Figure A.26: Zygomatic orientation in relation to maxilla. From left to right: Abri Pataud 1, strongly angled zygomatic (state 0); Petralona, curved zygomatic (state 1); La Ferrassie 1, oblique zygomatic (state 2). According to Condemi [3] the facies lateralis of the zygomatic frontal process of classic Neandertals is generally flat while Middle-Eastern Neandertals display a more concave facies lateralis. The European Middle Pleistocene fossils also show this concavity on the external surface. #75: Facies lateralis of the zygomatic frontal process. 2 states 0.concave facies lateralis of the zygomatic frontal process 1.flat facies lateralis of the zygomatic frontal process The temporal margin of the zygomatic (temporal process) might display on its superior part a bulge variably protruding: the tuberculum marginale [55]. Depending on the degree of development of this bulge, the temporal margin of the zygomatic might be straight (tubercle absent), convex backward (tubercle weakly-developed) or displaying a proper bulge strongly protruding backward (tubercle well-developed). Weidenreich [29] included this character in his diagnosis of Homo erectus. #76: Development of a tuberculum marginale on the temporal margin of the zygomatic (Fig. A.27). 3 states 0.tuberculum marginale absent 1.tuberculum marginale weakly-developed 2.tuberculum marginale well-developed 27 Appendix A: Morphological features description Figure A.27: Tuberculum marginale on the temporal margin of the zygomatic. From left to right: Broken Hill, tuberculum marginale absent (state 0); Abri Pataud 1, tuberculum marginale weakly-developed (state 1); Petralona, tuberculum marginale well-developed (state 2). One or several foramina are generally displayed on the facies lateralis of the zygomatic. Maureille [55] observed different setting patterns of the foramina on the zygomatic of AMHs and Neandertals, the latter usually possessing multiple foramina forming an arc of a circle. #77: Number and positions of the zygomatico-facial foramina (Fig. A.28). 4 states 0.zygomatico-facial foramen absent 1.presence of one foramen 2.presence of multiple foramina 3.presence of multiple foramina forming an arc of a circle Figure A.28: Zygomatico-facial foramina forming an arc of a circle on La Chapelle-auxSaints zygomatic (state 3). #78: Configuration of the zygomatic body. 3 states 0.flat zygomatic body 1.concave zygomatic body 2.convex zygomatic body 28 Appendix A: Morphological features description The zygomaxillary tuberosity is a protuberance positioned on the external face of the zygomatic [58]. According to Weidenreich [29], this protuberance is positioned on the superior part of its body adjacent to the infra-orbital margin. However, the zygomaxillary tuberosity might also be observed on the lower part of the zygomatic body. #79: Zygomaxillary tuberosity. 3 states 0.absent zygomaxillary tuberosity 1.zygomaxillary tuberosity weakly-developed 2.present zygomaxillary tuberosity The morphology of AMHs’ maxilla (#80, 81, 82, 83) has been observed following Maureille [55] and Caparros [12] descriptions: the body of the maxilla is strongly flexed in the sagittal plane from the inferior orbital rim to the inferior margin of the maxilla; superiorly the maxilla displays a horizontal crest. Sergi [62] (see also [3, 55]) used three concavities: incurvatio inframalaris frontalis, incurvatio horizontalis and incurvatio sagittalis which are useful to describe AMHs’ maxilla’s morphology as well as older fossil specimens’ maxilla. Thus, in the present study we coded these three curvatures as well as the more traditional canine fossa (a hollowing on the anterior surface of the maxilla, [55]). #80: Incurvatio horizontalis. 3 states 0.flat anterior surface of the maxilla 1.horizontal hollowing on the anterior surface of the maxilla 2.incurvatio horizontalis present #81: Incurvatio sagittalis.3 states 0.flat anterior surface of the maxilla 1.sagittal hollowing on the anterior surface of the maxilla 2.incurvatio sagittalis present #82: Incurvatio inframalaris frontalis (Fig. A.29). 4 states 0.straight infero-lateral border of the maxilla 1.the infero-lateral border of the maxilla is slightly curved at the meeting point with the maxillo-alveolar margin 2.most of the infero-lateral border of the maxilla is weakly-curved 3.the infero-lateral border of the maxilla displays two curvatures strongly-marked 29 Appendix A: Morphological features description Figure A.29: Incurvatio inframalaris frontalis. From left to right: La Chapelle-aux-Saints, absent (state 0); Gibraltar 1, slightly curved infero-lateral border of the maxilla (state 1); Broken Hill, most of the infero-lateral border of the maxilla is weakly-curved (state 2); Abri Pataud 1, two strongly-marked curvatures on the inferolateral border of the maxilla (state 3). The canine fossa is described by Maureille [55] as a well-defined hollowing on the anterior infraorbital surface of the maxilla, just under the orbital foramen. #83: Canine fossa (Fig. A.30). 4 states 0.absent 1.slight hollowing weakly-defined 2.hollowing well-defined 3.deep hollowing, well-defined Figure A.30: Canine fossa: La Chapelle-aux-Saints, absent (state 0); Gibraltar 1, slight hollowing weakly-defined (state 1); Steinheim, hollowing well-defined (state 2); Cro-Magnon 1, deep hollowing, well-defined (state 3). Following Condemi [3], we evaluated the orientation of the mid-face in relation to the inferior orbital margin. Condemi described the Neandertals mid-face as being steadily convex and more continuous, with orbital rim, than in modern humans. #84: Orientation of the mid-face in relation to the inferior orbital margin. 3 states 30 Appendix A: Morphological features description 0.weakly discontinuous, steady convexity between the infra-orbital margin and the maxilla 1.discontinuous, infra-orbital margin and maxilla are oblique 2.strongly discontinuous, the maxilla is vertical to concave in relation to the infra-orbital margin Generally there is only one infra-orbital foramen in current humans, but multiple foramina may be observed. The proportion of multiple infra-orbital foramina in the current population is 15.8% according to Berry and Berry [63], while for Maureille [55] it varies between 18.8% and 46.9% depending on the population. #85: Number of infra-orbital foramina. 2 states 0.one foramen 1.multiple foramina The infra-orbital foramen is usually in a high position in current populations and in a low position in Neandertals [3]. According to Patte [56], the infra-orbital foramen is positioned between 4 and 10 mm from the inferior orbital margin, while one of us (AM) found that in 95% of the AMH sample of a previous study [21] the foramen was positioned at more than 10.78 mm. We use 11 mm as a limit between low and high position, and when there are more than one foramen we use the mean of the distances of the position of each foramen. #86: Position of the infra-orbital foramen on the maxilla in relation to the infra-orbital margin. 2 states 0.low (≥ 11 mm 1.high (< 11 mm) #87: Nasoalveolar clivus length (Fig. A.31). 2 states 0.short nasoalveolar clivus (≤ 17 mm 1.long nasoalveolar clivus (> 17 mm) 31 Appendix A: Morphological features description Figure A.31: Nasoalveolar clivus length (h) is measured from the line joining the right and left narials (n) to the prosthion (p). From left to right: Abri Pataud 1, short nasoalveolar clivus (state 0); La Chapelle-aux-Saints, long nasoalveolar clivus (state 1). The position of the insertion of the facial crest on the maxillo-alveolar margin is used to characterise the forward projection of the lower part of the face. Howells [64] suggested that the forward projection of the Neandertal lower face was due to the forward projection of the dental arch and the absence of curvature on the zygomatico-maxilla region. In current populations the facial crest reaches the maxillo-alveolar margin at the level of the M1-M2 septum in 66.5% of the cases and at the level of the M1 in 23.5% of the cases, while in Neandertals the facial crest’s position on the maxillo-alveolar margin is more posterior [55]. #88: Position of the insertion of the facial crest on the maxilla-alveolar margin. 3 states 0.P4 and P4-M1 1.M1 and M1-M2 2.M2 and posterior The morphological variation of the maxillo-alveolar region is high in current and fossil populations [55]. However, bony superstructures are more common in Neandertal and in Middle Pleistocene fossils [29, 55]. #89: Alveolar torus on the vestibular aspect of the alveolar process. 2 states 0.absent 1.present #90: Alveolar torus on the lingual aspect of the alveolar process. 2 states 0.absent 1.present #91: Torus palatinus on the inter-maxillary suture. 2 states 0.absent 1.present 32 Appendix A: Morphological features description A posterior position of the incisive foramen on the palate is often used to describe Neandertal or Homo erectus s.l. populations [1-3, 29]. We evaluated this feature using the position of the posterior part of the incisive foramen in relation to the septum C-P3. #92: Incisive foramen position on the palate. 2 states 0.posterior to the septum C-P3 1.anterior to the septum C-P3 #93: Form of the dental arch in norma basalis. 3 states 0.the margins of the dental arch are parallels 1.the margins of the dental arch are divergent posteriorly 2.the margins of the dental arch are 33 convergent posteriorly Appendix A: Morphological features description 34