Uphill All the Way: The Fortunes of Progressivism, 1919-1929

Kevin C. Murphy

Submitted in partial fulfillment of the

requirements for the degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

2013

© 2013

Kevin C. Murphy

All rights reserved

ABSTRACT:

Uphill All the Way: The Fortunes of Progressivism, 1919-1928

Kevin C. Murphy

With very few exceptions, the conventional narrative of American history dates the end

of the Progressive Era to the postwar turmoil of 1919 and 1920, culminating with the election of

Warren G. Harding and a mandate for Normalcy. And yet, as this dissertation explores,

progressives, while knocked back on their heels by these experiences, nonetheless continued to

fight for change even during the unfavorable political climate of the Twenties. The Era of

Normalcy itself was a much more chaotic and contested political period – marked by strikes, race

riots, agrarian unrest, cultural conflict, government scandals, and economic depression – than the

popular imagination often recalls.

While examining the trajectory of progressives during the Harding and Coolidge years,

this study also inquires into how civic progressivism - a philosophy rooted in preserving the

public interest and producing change through elevated citizenship and educated public opinion –

was tempered and transformed by the events of the post-war period and the New Era.

With an eye to the many fruitful and flourishing fields that have come to enhance the

study of political ideology in recent decades, this dissertation revisits the question of progressive

persistence, and examines the rhetorical and ideological transformations it was forced to make to

remain relevant in an age of consumerism, technological change, and cultural conflict. In so

doing, this study aims to reevaluate progressivism's contributions to the New Era and help to

define the ideological transformations that occurred between early twentieth century reform and

the liberalism of the New Deal.

Uphill All The Way: Table of Contents

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .............................................................................................vi

DEDICATION ................................................................................................................... x

PREFACE .......................................................................................................................... xi

INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1

The Bourne Legacy .................................................................................................. 1

Progressives and Progressivism ............................................................................ 7

Cast of Characters.................................................................................................. 12

Review of the Literature ....................................................................................... 15

Chapter Outline ..................................................................................................... 17

PROLOGUE: INAUGURATION DAY, 1921 .............................................................. 22

PART ONE: CRACK-UP: FROM VERSAILLES TO NORMALCY ........................ 30

CHAPTER ONE: THE “TRAGEDY OF THE PEACE MESSIAH” .................... 31

An American in Paris ............................................................................................ 32

A Human Failure ................................................................................................... 40

A Failure of Idealism? ........................................................................................... 47

The Peace Progressives ......................................................................................... 52

CHAPTER TWO: THE “LEAGUE OF DAM-NATIONS” .................................. 58

Collapse at Pueblo ................................................................................................. 58

The Origins of the League .................................................................................... 61

The League after Armistice .................................................................................. 67

The Third Way: Progressive Nationalists .......................................................... 71

The Treaty Arrives in the Senate ......................................................................... 79

The Articles of Contention ................................................................................... 82

Things Fall Apart ................................................................................................... 94

Aftermath.............................................................................................................. 107

CHAPTER THREE: CHAOS AT HOME............................................................. 111

i

Terror Comes to R Street. ................................................................................... 112

The Storm before the Storm. .............................................................................. 116

Enemies in Office, Friends in Jail. ..................................................................... 133

Mobilizing the Nation ......................................................................................... 139

The Wheels Come Off ......................................................................................... 146

On a Pale Horse ................................................................................................... 150

Battle in Seattle ..................................................................................................... 157

The Great Strike Wave ........................................................................................ 162

Steel and Coal....................................................................................................... 170

The Red Summer ................................................................................................. 184

The Forces of Order ............................................................................................. 194

Mr. Palmer’s War................................................................................................. 205

The Fever Breaks ................................................................................................. 220

The Best Laid Plans ............................................................................................. 229

CHAPTER FOUR: THE TRIUMPH OF REACTION ........................................ 241

A Rematch Not to Be ........................................................................................... 241

The Man on Horseback ....................................................................................... 245

The Men in the Middle ....................................................................................... 250

I’m for Hiram ....................................................................................................... 254

Visions of a Third Term ...................................................................................... 257

Ambition in the Cabinet ..................................................................................... 260

The Democrats’ Lowden .................................................................................... 263

The Great Engineer ............................................................................................. 265

The Smoke-Filled Room ..................................................................................... 275

San Francisco ........................................................................................................ 285

A Third Party?...................................................................................................... 296

Mr. Ickes’ Vote ..................................................................................................... 318

Countdown to a Landslide ................................................................................ 331

ii

The Triumph of Reaction ................................................................................... 347

PART TWO: CONFRONTING NORMALCY ......................................................... 356

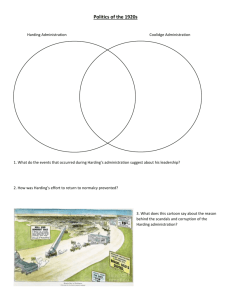

CHAPTER FIVE: THE POLITICS OF NORMALCY ......................................... 357

The Harding White House ................................................................................. 357

Organizing in Opposition .................................................................................. 373

Lobbies Pestiferous and Progressive ................................................................ 393

The Taint of Newberryism ................................................................................. 400

The Harding Scandals ......................................................................................... 409

Tempest from a Teapot ....................................................................................... 417

CHAPTER SIX: LEGACIES OF THE SCARE ..................................................... 439

The Education of Jane Addams ......................................................................... 440

Prisoners of Conscience ...................................................................................... 444

The Laws and the Court ..................................................................................... 458

The Shoemaker and the Fish-Peddler .............................................................. 474

The Shame of America ........................................................................................ 491

The Right to Organize ......................................................................................... 519

Professional Patriots ............................................................................................ 547

CHAPTER SEVEN: AMERICA AND THE WORLD ........................................ 565

The Sins of the Colonel ....................................................................................... 565

Guarding the Back Door ..................................................................................... 575

Disarming the World .......................................................................................... 589

The Outlawry of War .......................................................................................... 606

The Temptations of Empire ............................................................................... 620

Immigrant Indigestion ........................................................................................ 650

CHAPTER EIGHT: THE DUTY TO REVOLT .................................................... 670

Indian Summer .................................................................................................... 670

Now is the Time… ............................................................................................... 678

Hiram and Goliath .............................................................................................. 691

iii

Coronation in Cleveland .................................................................................... 711

Schism in the Democracy ................................................................................... 722

Escape from New York ....................................................................................... 734

Fighting Bob ......................................................................................................... 753

Coolidge or Chaos ............................................................................................... 766

The Contested Inheritance ................................................................................. 775

Reds, Pinks, Blues, and Yellows ........................................................................ 787

The Second Landslide ......................................................................................... 805

PART THREE: A NEW ERA ....................................................................................... 821

CHAPTER NINE: THE BUSINESS OF AMERICA ........................................... 822

Two Brooms, Two Presidents ............................................................................ 822

A Puritan in Babylon........................................................................................... 831

Hoover and Mellon ............................................................................................. 840

Business Triumphant .......................................................................................... 863

CHAPTER TEN: CULTURE AND CONSUMPTION ....................................... 881

A Distracted Nation ............................................................................................ 882

The Descent of Man............................................................................................. 900

The Problem of Public Opinion ......................................................................... 906

Triumph of the Cynics ........................................................................................ 923

Scopes and the Schism ........................................................................................ 943

Not with a Bang, But a Whimper ...................................................................... 961

New World and a New Woman........................................................................ 972

The Empire and the Experiment ..................................................................... 1014

CHAPTER ELEVEN: NEW DEAL COMING .................................................. 1046

A Taste of Things to Come ............................................................................... 1046

The General Welfare ......................................................................................... 1053

The Sidewalks of Albany .................................................................................. 1070

For the Child, Against the Court ..................................................................... 1079

iv

The Rivers Give, The Rivers Take ................................................................... 1091

CHAPTER TWELVE: MY AMERICA AGAINST TAMMANY’S ................. 1112

The Republican Succession .............................................................................. 1112

The Available Man ............................................................................................ 1132

Hoover v. Smith ................................................................................................. 1150

The Third Landslide .......................................................................................... 1184

CONCLUSION: TIRED RADICALS ........................................................................ 1194

The Strange Case of Reynolds Rogers ............................................................ 1194

The Progressive Revival ................................................................................... 1199

Confessions of the Reformers .......................................................................... 1203

BIBLIOGRAPHY ......................................................................................................... 1218

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

“Perhaps you may ask, ‘Does the road lead uphill all the way?’ And I must answer, ‘Yes,

to the very end.’ But if I offer you a long, hard struggle, I can also promise you great rewards.”

These are the words of Grace Abbott, the second head of the Children’s Bureau,

summing up her lifelong experience as a progressive social worker and children’s advocate in a

1934 commencement address. This quote is also the epigram of Clarke Chambers’ 1963 book,

Seedtime of Reform, one of the first book-length examinations of the fate of progressivism in the

Twenties. It is certainly a very reasonable approximation of the experience of many of the

progressives in this study during the decade in question. And, as anyone who has ever trod along

the long, lonely road of academe can tell you, “Uphill All the Way” is also an apt summary of

the often-Sisyphean task of researching and writing a history dissertation. This particular boulder

rolled back to the starting point many times over in the seven years since I first embarked on this

project. It would never have made it over that final crest without the support and encouragement

of the many listed below.

I would first like to thank my advisor, Alan Brinkley, the other members of my

dissertation committee, Elizabeth Blackmar, Eric Foner, David Greenberg, and Ira Katznelson,

and the American history faculty of Columbia University for their advice, their teachings, and

most of all their patience. Thank you also to the hardworking and friendly archivists at the

Library of Congress, where I conducted the bulk of my offline research.

I also want to thank my colleagues at the Office of Rosa DeLauro, where I began fulltime work as a speechwriter in the midst of this project, and who were kind enough to offer their

vi

support and tolerance when I decided to complete in my off hours what I had started years prior.

Special thanks go to Liz Albertine, Eric Anthony, Kevin Brennan, Melinda Cep, Sarah Dash,

Kelly Dittmar, Matt Doyle, Sara Lonardo, Asa Lopatin, Letty Mederos, Beverly Pheto, Kaelan

Richards, Brian Ronholm, Elyse Schoenfeld, Lona Watts, Megan Whealan, Jasmine Zamani,

Dan Zeitlin, and Congresswoman DeLauro herself, who, ninety years later, continues the same

fight for a more progressive America that is chronicled in these pages.

This dissertation, like most other works of research, could never have come together

without the hard work of the dozens of scholars who gleaned these archives and pulled on these

same threads before. So I would like to thank the many historians whose work I have cited here,

and whose body of research was indispensable to me – particularly Leroy Ashby, Wesley M.

Bagby, Dorothy Brown, Clarke Chambers, Nancy Cott, Alan Dawley, Robert David Johnson,

David Kennedy, Thomas Knock, William Leuchtenburg, Laton McCartney, Ronald K. Murray,

Donn Neal, Burl Noggle, David Pietrusza, Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., and Howard Zinn. I also want

to acknowledge and thank Dr. Carlanna Hendrick, my high school American history teacher

who, two decades ago, helped set me on the path that culminated in this project today.

Along with my debt to the past, I want to acknowledge my debt to the future. I could

never have completed this project without the gigantic and growing archive of resources

available to all via the Internet. From the Google Books and UNZ.org portals, which make

available thousands of useful primary and secondary sources to anyone who goes looking, to

magazines like TIME, The New Republic, and The Nation, who now have all of their backcatalog online for subscribers’ use, the practice of historical research is changing for the better,

and I and this study have been clear beneficiaries.

vii

Thanks also to my friends and fellow boulder-pushers in the Columbia History program,

who helped to enrich my days as a graduate student and keep my spirits up in the early days of

this project – especially Sarah Bridger, Ben and Vivian Coates, Alex Cummings, Jason

Governale, Susan Jean, Ryan Jones, Emily Lieb, Liam Moore, Amy Offner, Giovanni Ruffini,

Ted Wilkinson, and Josh Wolff. Thank you all.

I also want to thank my other friends in and around New York who helped sustain me

through the graduate school years, particularly Olaf Bertram-Nothnagel, Lauren Brown, Mike

Fernandez, Moses Gates, Maria Gambale and Zachary Taylor, Arkadi Gerney and Nancy

Meakem, Lisa Halliday, Jennifer Martinez, Mark Noferi, Amanda Rawls, Alex Travelli, Joyce

Wu, and Daniel Yohannes. Thank you also to my friends in DC: John Anderson, Steve Bogart

and Lynette Millett, Tim Cullen, Lotta Danielsson, Mike Darner, Tony Eason, Alex Lawson and

Laila Leigh, Marisa McNee, Dave Meyer, Matt Stoller, and Shaunna Thomas. A special thank

you to Erin Mastrangelo, who helped give me the strength and confidence, when I found myself

back at square one once again, to make one final, sustained push up the hill. And thank you to

all the friends and readers who have sustained me at Ghost in the Machine over the years.

And the deepest of thanks to my closest and dearest friends, who have provided much

support and encouragement over the long course of this project – David Demian, Jeremy

Derfner, Marcus Hirschberg and Bea Wikander, Kofi Kankam, Randolph Pelzer, Danny

Sanchez, David Weaver, and Jonathan Wolff. And many thanks to my family – my sisters

Gillian and Tessa, my brother and brother-in-law Thad and Ethan, and especially my parents

Paul and Carol, for their love, encouragement, and support throughout every stage of this

process.

viii

Finally, I want to acknowledge my faithful sheltie hound Berkeley, who came with me as

a young pup to graduate school in the fall of 2001, and who saw this project through with me

until its end in the fall of 2012. It has seemed like a lifetime for the both of us. And yes, now we

can go to the dog park.

-

ix

Kevin C. Murphy,

October 2012

DEDICATION

For My Parents

x

PREFACE

“THEM was the days! When the muckrakers were best sellers, when trust busters were

swinging their lariats over every state capitol, when ‘priviledge’ shook in its shoes, when

God was behind the initiative, the referendum, and the recall – and the devil shrieked

when he saw the short ballot, when the Masses was at the height of its glory, and Utopia

was just around the corner.

…Now look at the damned thing. You could put the avowed Socialists into a roomy new

house, the muckrakers have joined the breadlines, Mr. Coolidge is compared favorably to

Lincoln, the short ballot is as defunct as Mah Jong, Mr. Eastman writes triolets in

France, Mr. Steffens has bought him a castle in Italy, and Mr. Howe digs turnips in

Nantucket.

Shall we lay a wreath on the Uplift Movement in America? I suppose we might as well.”

-- Stuart Chase, 19261

“I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of

Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn and his dream must have seemed

so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind

him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the

republic rolled on under the night.

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us.

It eluded us then, but that’s no matter – tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our

arms farther…And one fine morning --So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

-- F. Scott Fitzgerald, 1925.2

1

2

Stuart Chase, “Where are the Pre-War Radicals?” The Survey, February 1, 1926, 563

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Great Gatsby (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1925), 189.

xi

1

INTRODUCTION

The “Twenties were really the formative years of modern American society.” – George Mowry,

intro to The Twenties: Fords, Flappers, and Fanatics3

“The decade sits solidly at the base of our culture…This was the first serious attempt of

Americans to make their peace with the twentieth century.” – Paul M. Carter4

“Many difficulties come from the simple failure of our ideas and conventions, not to mention our

prejudices, to keep up with the pace of material change. Our environment moves much faster

than we do.” – Jane Addams, 1930.5

***

The Bourne Legacy

“One has a sense of having come to a sudden, short stop at the end of an intellectual era,”

declared an appalled Randolph Bourne in 1917, as the American left lurched into World War

One.6 While the nation’s progressive president bade his countrymen “make the world safe for

democracy” and one of its foremost intellectuals waxed enthusiastic about “the social

possibilities of war,” Bourne portended dire consequences ahead for the forces of reform in

American life. “It must never be forgotten that in every community it was the least liberal and

least democratic elements among whom the preparedness and later the war sentiment was

found,” he argued. “The intellectuals, in other words, have identified themselves with the least

democratic forces in American life. They have assumed the leadership for war of those very

classes whom the American democracy had been immemorially fighting. Only in a world where

irony was dead could an intellectual class enter war at the head of such illiberal cohorts in the

3

Paul Carter, The Twenties in America (New York: Crowell, 1975), 28.

Dorothy Marie Brown, Setting a Course: American Women in the 1920s (Boston: G.K. Hall, 1987), 1.

5

Jane Addams, The Second Twenty Years at Hull House (New York: MacMillan Company, 1930), 392.

6

Randolph Silliman Bourne and Olaf Hansen, The Radical Will : Selected Writings, 1911-1918 (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1992), 343.

4

2

avowed cause of world-liberalism and world-democracy.” “The whole era,” concluded Bourne in

disgust, “has been spiritually wasted.”7

Nothing if not prescient, Randolph Bourne’s words have become an epitaph for the

Progressive Era in the decades since his untimely death in 1918.8 Indeed, with very few

exceptions, the standard, textbook interpretation of American history dates the end of the

progressive movement to the postwar turmoil of 1919 and 1920, culminating in the election of

Warren G. Harding and a mandate for Normalcy.9 Over the next decade, so the story goes, the

nation entered a New Era marked by conservatism, consumerism, and cultural conflict, three C’s

for which the progressive ideology of yore seemed wholly inadequate and obsolete.10

Progressives, at the center of American political life prior to the Great War, became victims to

the cruel disillusion of un-fulfillment – They were, as one historian framed the prevailing tale in

7

Ibid, 308.

Indeed, one does not have to look very far to find Bourne playing the grim harbinger of progressive demise in

several narratives of the period. “Bourne was right: the progressives needed the war effort, and the war effort needed

them,” concludes Michael McGerr in his recent synthesis A Fierce Discontent. “What was canny intuition in 1917

became obvious reality by 1919 and 1920.” In The Story of American Freedom, Eric Foner uses Randolph Bourne to

similar purpose. “Bourne’s prescience soon became apparent…[the war] laid the foundation not for the triumph of

Progressivism but for one of the most conservative decades in American history.” Michael E. McGerr, A Fierce

Discontent : The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870-1920 (New York: Free Press, 2003),

283,310.. Eric Foner, The Story of American Freedom, 1st ed. (New York: W.W. Norton, 1998), 177..

9

“No concept,” argued historian Burl Noggle in 1966, “has endured longer or been more pervasive among historians

than the one which views the 1920s as a time of reaction and isolation induced by the emotional experience of

World War I.” Milton Plesur, The 1920's: Problems and Paradoxes; Selected Readings (Boston,: Allyn and Bacon,

1969). p. 283. Similarly, Arthur Link remarked in 1959 that, “[w]riting without out much fear or much research (to

paraphrase Carl Becker’s remark), we recent American historians have gone indefatiguably to perpetuate hypotheses

that either reflected the disillusionment and despair of contemporaries, or once served their purpose in exposing the

alleged hiatus in the great continuum of twentieth-century reform.” Arthur Link, “What happened to the Progressive

Movement in the 1920s?” The American Historical Review, Vol. 64, No. 4 (Jul. 1959), 833.

10

As LeRoy Ashby sums it up in his study of William Borah, “by the Twenties, [the] prewar progressive consensus

was in shambles. As the unifying spirit and confidence of the earlier years dissolved, the internal weaknesses of

progressivism became all too apparent. One agonizing problem – and one which Borah symbolized so vividly – was

the need to square the basically rural and agrarian social vision of progressivism with the demands of an ethnically

and racially diverse nation. Although many progressive leaders were urban residents, their roots and biases tended to

be overwhelmingly rural. Their penchant for individualism, their hostility to special privilege, and their Protestant

faith comprised the intellectual and cultural baggage which they carried with them from their village backgrounds.”

LeRoy Ashby, The Spearless Leader; Senator Borah and the Progressive Movement in the 1920's (Urbana,:

University of Illinois Press, 1972), 7.

8

3

1959, “stunned and everywhere in retreat along the entire political front, their forces

disorganized and leaderless, their movement shattered, their dreams of a new America turned

into agonizing nightmares.”11 And only after the earth-shattering tumult of the Great Depression,

nine years hence, would a revived and rethought liberal creed rise again to national prominence,

like a phoenix from out the ashes of progressive despair.

It makes for a good story, and, like most neat narrative conventions of synthesis, there is

indeed much truth to it. Clearly, many Progressive contemporaries saw events as such: In 1920,

Senator Hiram Johnson lamented “the rottenest period of reaction that we have had in many

years.” Harold Ickes reflected seven years later that 1927 still “isn’t the day for our kind of

politics.” And Progressive luminary Jane Addams looked back at the entirety of the Twenties as

“a period of political and social sag.”12

And, yet, the progressive experience from 1919-1929, while perhaps primarily a

declension narrative, deserves to be further explored. In the words of Ellis Hawley, “[d]elving

beneath the older stereotypes of ‘normalcy’ and ‘retrenchment,’ scholars have found unexpected

survivals of progressivism.”13 Indeed, as historian Leroy Ashby notes of the first election cycle

after Harding’s victory, “the 1922 campaigns seemed positive proof that the progressive

movement was regaining some of its prewar vigor,” with a number of progressive candidates in

Congress and gubernatorial races, such as Burton Wheeler, Gifford Pinchot, Al Smith, and

Fiorello LaGuardia, defeating their more conservative opposition. (Indeed, after the election

11

Link, 834.

McGerr, A Fierce Discontent : The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870-1920, 313,15.

Ashby, The Spearless Leader; Senator Borah and the Progressive Movement in the 1920's, 284.

13

Ellis Hawley, “Herbert Hoover, the Commerce Secretariat, and the Vision of an Associative State, 1921-1928,”

The Journal of American History, Vol. 61, No. 1 (Jun. 1974), 116.

12

4

returns, The New Republic went so far as to declare “Progressivism Reborn.”)14 And, while the

failed third party bid of Robert La Follette in 1924 saw progressivism “fragmented, leaderless,

and far removed from the optimism that had followed the 1922 election,” America’s choice for

President in 1928 nevertheless consisted of two candidates with some progressive credentials,

Secretary of Commerce Herbert Hoover and Governor Al Smith of NewYork.15

Noting this discrepancy between narrative and evidence in 1959, historian Arthur Link

suggested in his essay “What Happened to the Progressive Movement in the 1920’s?” that

“perhaps it is high time that we discard the sweeping generalizations, false hypotheses, and

clichés that we have so often used in explaining and characterizing political developments from

1918 to 1929…When we do this we will no longer ask whether the progressive movement was

defunct in the 1920s. We will only ask what happened to it and why.”16

With Link’s fifty-year-old challenge as a guide stone, and with an eye to all the broader

and exciting new lines of inquiry that have opened in American history since, this study aims to

reexamine the fortunes of progressivism in the decade from 1919 to 1929. How were prominent

progressives impacted by the experiences of the immediate post-war era? How did they navigate

their way through the 1920s? What causes did they take up and what contributions did they make

to the politics of the period? And, perhaps most importantly, what sort of rhetorical and

ideological transformations were progressives forced to make to keep their ideology practicable

and relevant in an age of consumer culture and cultural conflict?

14

Ashby, The Spearless Leader; Senator Borah and the Progressive Movement in the 1920's, 56-57.

Ibid., 179.

16

Link, 851.

15

5

As this study explores, progressives were badly jarred by the failures of Wilsonism and

the excesses that marked the annus horribilis of 1919, and many never recovered. But others

persisted even during the unfavorable political climate of the Twenties.

Shocked by the outright repression and virulent nationalism that had accompanied World

War I and the subsequent Red Scare, some progressives began rethinking the appropriate role of

state power and the importance of civil liberties, just as others crafted draconian immigration

reforms that followed the letter, if not the spirit, of earlier attempts to "Americanize" citizens.

Wary of the influx of private interests into government life that accompanied the return to

normalcy, some progressives, particularly the Western mavericks in the Senate, battled

corruption on both ends of Washington, and reaffirmed the centrality of the public interest in

endeavors ranging from radio regulation to public power. Progressive peace activists and

organizations emerged at the forefront of an international disarmament movement. Newly

empowered with the vote, many progressive women looked to fashion a stronger federal role

over the realms of education, health care, and child welfare.

The Progressive-headed "Committee of Forty-Eight" attempted to forge an independent

political movement behind insurgent Senator Robert M. LaFollette, who captured approximately

17% of the vote in 1924. The NAACP, under the leadership of W.E.B. Du Bois, worked to

improve the lives of African-Americans in southern states and northern cities, and began crafting

its legal strategy to dismantle segregation. And countless progressive reformers, in laboratories

as diverse as Al Smith's New York and Herbert Hoover's Commerce Department, experimented

6

with ideas, ranging from social insurance to associationalism to regional development, which

would later form the centerpiece of Franklin Roosevelt's New Deal.

But, as times changed, so too did progressivism, and not the least because many of its

leading lights either grew tired and frail or passed beyond the veil. From World War I on,

progressives continually found their foundational faith in individual improvement and the

infallibility of an informed electorate tested. The “business bloc” that formed behind Harding

and Coolidge, coupled with cultural conflicts of the period, as embodied most famously by the

Scopes Trial and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan, further strained the progressive belief in a

crusading, dispassionate, and well-informed middle-class as a vehicle for change. And as

progressives grappled with the growing centrality of consumerism and consumerist thinking in

all aspects of American life and governance, they had also to confront the abysmal failure of and fallout from - Prohibition, the movement's most ambitious moral experiment, and a telling

indicator of the limits of reform.

Over the course of the decade, as progressives saw setback after setback and everything

from advertising to Freudianism suggested that base instinct all too often prevailed over reason,

many seemed to lose their abiding faith in the central touchstones of their ideology: the concept

of the public interest, the transformative power of public opinion, and the capacity for individual

improvement. Instead of conceiving themselves as the vanguard of the popular will, many now

defined themselves as an oppositional elite. Chiding themselves for their earlier ambitions, and

lamenting what they now thought of as hopeless naivete, they turned inward and apart. They

began to dwell less on how to mold good citizens and more on questions of economic power and

individual rights. And so, even as they laid down much of the policy groundwork for the New

7

Deal, progressives tempered by the post-war experience also bequeathed a new language and

disposition toward reform that would characterize the movement for decades to come.

Progressives and Progressivism

But what is progressivism? And who were the progressives? These are two seemingly

straightforward questions that have nevertheless haunted the efforts of many an enterprising

historian over the years. Regarding the first of these queries, any satisfactory working definition

of progressivism as a guiding political ideology must clearly be expansive and flexible enough to

allow for considerable variation, encompassing New Nationalists, Wilsonians, prohibitionists,

and suffragettes. As Robert Crunden writes in Ministers of Reform, progressives “shared no

platform, nor were they members of a single movement,” but they “shared moral values.” It is

tempting to utilize a Potter Stewart definition for progressivism and simply argue that one knows

it when they see it.17

In broad terms, and for the purposes of this study, progressivism constituted what Samuel

Hays famously referred to as a “response to industrialism,” and to the “fundamental

redistributions of wealth, power, and status” that occurred in its wake. In others words,

progressivism arose in reaction to the unmitigated corporate power that had defined the Gilded

Age, and progressives usually defined themselves in opposition to that power, even as they

embraced some of its methods. “Ultimately,” as historian John Buenker summarizes Hays’

thesis, “nearly everyone began to perceive that the only way to cope with his problems and to

17

Robert Morss Crunden, Ministers of Reform: The Progressives’ Achievement in American Civilization, 1889-1920

(Chicago: Illini Books, 1984), ix. Daniel Rodgers’ essay “In Search of Progressivism” ably summarizes the rise and

fall of progressivism as a unifying construct up through 1982. More recently however, syntheses such as James

Kloppenberg’s Uncertain Victory, Michael McGerr’s A Fierce Discontent (2003) and Rodgers’ own Atlantic

Crossings (1998) have attempted to reconstruct progressivism as a cohesive principle.

8

advance or protect his interests was to organize, for the new environment put a premium on

large-scale enterprise. For most people, as Hays so effectively put it, it was a case of ‘organize or

perish.’”18

However hotly contested other aspects of progressivism have been over the years,

historians have also tended to agree that progressives generally hailed from the middle-class

(Indeed, this is as often meant as an epithet as much as a descriptor.19) As Michael McGerr puts

it, progressivism was “the creed of a crusading middle class,” a bold and brazen attempt “to

transform other Americans, to remake the nation’s feuding, polyglot population in their own

middle-class image” and “build what William James sneeringly but accurately labeled the

‘middle-class paradise.’”20

In addition, progressivism as a public philosophy hewed closely to what political scientist

Michael Sandel has described as “civic republicanism.” Central to this theory of civic

republicanism, writes Sandel, “is the idea that liberty depends on sharing in self-government:

It means deliberating with fellow citizens about the common good and helping to shape the

destiny of the political community. But to deliberate well about the common good requires more

than the capacity to choose one’s ends and to respect other’s rights to do the same. It requires a

knowledge of public affairs and also a sense of belonging, a concern for the whole, a moral bond

with the community whose fate is at stake. To share in self-rule, therefore requires that citizens

possess, or come to acquire, certain qualities of character, or civic virtues. But this means that

18

John D. Buenker, Urban Liberalism and Progressive Reform (New York: Norton, 1978).

In his overview of recent progressive historiography, historian Robert D. Johnston of Yale suggests that the

considerable contempt for middle-class reform among historians may have entered a period of thaw. “[P]eople in the

middle,” he writes, “—and not just African Americans—throughout our past have developed and sustained a wide

variety of democratic radicalisms, perhaps no more so than during the Progressive Era. Although historians have by

no means fully grappled with the implications of the intellectual rehabilitation of the American middling sorts, it is

clear that the (still far-too-incomplete) scholarly rise of the middle class has opened up a wide swath of intellectual

terrain, making it possible to talk about democracy and Progressivism in exciting new ways.” Robert D. Johnston,

“Re-Democratizing the Progressive Era: The Politics of Progressive Era Historiography.” Journal of the Gilded Age

and Progressive Era, January 2002.

20

McGerr, A Fierce Discontent : The Rise and Fall of the Progressive Movement in America, 1870-1920, xiv-xv.

19

9

republican politics cannot be neutral toward the values and ends its citizens espouse. The

republican conception of freedom, unlike the liberal conception, requires a formative politics, a

politics that cultivates in citizens the qualities of character self-government requires.21

In other words, whether they perceived the most dangerous threat to the nation to be

unfettered capitalism, monopoly power, moral hygiene, ethnic political machines, or the demon

rum, progressives aimed to preserve the forms and prerequisites of democratic citizenship from

outside dangers and to inculcate some form of civic virtue into the electorate. In effect, the

overarching goal of progressivism was to defend the American experiment against the

vicissitudes of capitalism and vice, in part by transforming and “uplifting” American citizens.

Progressives also all generally agreed on certain fundamental principles of change. First,

that men and women could be molded. In the words of New Republic editor Herbert Croly,

“democracy must stand or fall on a platform of possible human perfectibility. If human nature

cannot be improved by institutions, democracy is at best a more than usually safe form of

political organization.” Second, humans had the power to improve their communities and

themselves by sheer force of applied reason. Following from this, the most powerful force for

change in the world was enlightened public opinion. “[I]f the people knew the facts about

inhuman working conditions and the neglect of children,” argued Frances Perkins in one of

innumerable examples, “they would desire to act morally and responsibly.”22

In Reform, Labor, and Feminism, her 1988 study of Margaret Dreier Robins and the

Women’s Trade Union League, Elizabeth Payne eloquently defines progressivism as “the last,

21

Michael J. Sandel, Democracy's Discontent : America in Search of a Public Philosophy (Cambridge, Mass.:

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1996).

22

David Danbom, The World of Hope: Progressives and the Struggle for an Ethical Public Life (Philadelphia:

Temple University Press, 1987), 137. Clarke Chambers, Seedtime of Reform: American Social Service and Social

Action, 1918-1933 (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1963), 4.

10

full-blown articulation of that optimistic, republican, tolerant, and liberal Protestant view of the

individual and society that had informed America for one hundred years and that found its most

eloquent statement in Ralph Waldo Emerson’s call for the reformation of man. That tradition

saw the individual as possessing enormous potential for good, which could only be realized by a

properly structured society.”23

In Payne’s casting, the agenda of progressivism was “to pass the laws and create the

institutions that would release the individual’s potential both as a person and as a citizen. The

Progressive’s task was to liberate the individual from enslaving ignorance, debasing labor,

soulless pastimes, corrupt authority, and concentrated power. Once these multiple and

interlocking tyrannies were destroyed, the hitherto ‘hidden treasures’ of the self would be freed

for social expression; ‘every resource of body, mind, and heart’ would find vent in elevating

fellowship and individual excellence.”24

“Born between 1854 and 1874,” notes Robert Crunden similarly in Ministers of Reform,

“the first generation of creative progressives absorbed the severe, Protestant moral values of their

parents and instinctively identified those values with Abraham Lincoln, the Union, and the

Republican Party”:

23

Elizabeth Anne Payne, Reform, Labor, and Feminism : Margaret Dreier Robins and the Women's Trade Union

League, Women in American History (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 161.

24

Payne, 161. Anticipating Sandel’s civic republican argument, Payne describes later progressive discontent with

the New Deal in terms of a falling-away from notions of citizenship and the public good. “In the eyes of many

progressives,” she concludes, “the New Deal thrived on faction, class warfare, and special interests…[thus] the

broker state that the New Deal erected was intrinsically immoral because it had abandoned the conception of

citizenship…For the Progressives, ‘citizen’ and ‘reformer’ were virtually synonymous…A citizen was no more a

mere voter than a trade unionist was simply a dues payer. By participation in civic life, the citizen realized a

significant measure of self-government.” In short, she argues, the “New Deal and Progressivism may be seen as

reverse images of each other…New Dealers particularly scorned the old Progressive notions of self-reformation and

the good society as the ends of civic involvement.” This falling away from the old progressive ideals constitutes

much of the narrative of this study.

11

But they grew up in a world where the ministry no longer seemed intellectually respectable and

alternatives were few. Educated men and women demanded useful careers that satisfied

demanding consciences. They groped toward new professions such as social work, journalism,

academia, the law, and politics. In each of these careers, they could become preachers urging

moral reform on institutions as well as individuals… Men and women found that settlement

work, higher education, law, and journalism all offered possibilities for preaching without pulpits.

Over the long term, their goal was an educated democracy that would create laws that would, in

turn, produce a moral democracy.”25

David Danbom’s 1987 study The World of Hope: Progressives and the Struggle for an

Ethical Public Life also argues that progressives “were products of the Victorian age in which

they grew up. They reflected the Victorian faith in the individual and confidence in the

inevitability of human progress. They reflected also the crisis of authority in Victorian society

between religious and secular modes of understanding human affairs, and the value crisis raised

by the realities of a modernizing, industrializing society. These crises stimulated them to action,

leading them to attempt to infuse the values of private life into public life.” 26

As products of a Victorian mindset, Danbom argues, progressives “looked backward

rather than forward….their purpose was to hold a reluctant society to its basic values, not to pull

it into the modern age.” They also “embraced a religious and secular faith in individual selfdetermination that infused every area of human behavior.” In the words of progressive Frederic

C. Howe, former Commissioner of Ellis Island and author of the much-discussed memoir

Confessions of a Reformer, “early assumptions as to virtue and vice, goodness and evil remained

in my mind long after I had tried to discard them. That is, I think, the most characteristic

influence of my generation. It explains the nature of our reforms, the regulatory legislation in

25

Crunden, ix, 15.

Danbom, vii-viii. Only by grounding the Progressives in this fashion, Danbom argues, can we understand “their

altruism, their righteousness, their faith in people, their innocence, or their devotion to the public interest.”

26

12

morals and economics, our belief in men rather than in institutions and our messages to other

peoples.”27

Of course, by the late teens and especially by the Twenties, the world was a rather

different place than it had been only thirty years before. And especially by World War I, a

younger generation of progressives was emerging alongside that of Howe – a generation who,

while embracing the basic tenets of progressivism outlined above, were also more accustomed to

twentieth-century ferment. They would eventually comprise the vanguard of Franklin

Roosevelt’s New Deal, and the passing of the baton to them is one of the foci of this tale.

Cast of Characters

As noted above, progressives were a diverse lot, involved in a myriad of social and

political reforms. As such, this study focuses on distinct groups of reformers at various times.

Foremost among these are the progressive Senate bloc of the Mid-West and West, which

included William Borah, Robert La Follette, Hiram Johnson, George Norris, and Burton

Wheeler. As Leroy Ashby argues, these men of the West constituted the “main source of

progressive strength on Capitol Hill” during the Twenties.28

Also covered in this study are the writers and intellectuals of The New Republic, The

Nation, and The Survey, among them Herbert Croly, Walter Lippmann, Bruce Bliven, Paul

Kellogg, Oswald Villard, Freda Kirchwey, and Ernest Gruening. These journalists and scholars,

“middle class in background and deeply committed to the progressive movement,” argued

Charles Forcey in 1961, “were leaders among the men who sought to move liberalism in [a] new

27

28

Danbom, 4, 80.

Ashby, The Spearless Leader; Senator Borah and the Progressive Movement in the 1920's, 14-15.

13

direction,” both during and after the Progressive Era.29 “Journals like The New Republic and The

Nation,” argues Lynn Dumenil, “continued at the center of liberal thought” in the 1920’s. Also

part of this tale is H.L. Mencken, the acerbic and venerable columnist for the Baltimore Sun.

While Mencken fits in no easy box, his voice would be both one of the more prescient and most

distinctive of the era.30

Leaders of the women’s suffrage movement, as well as other prominent progressives

concerned with combating gender inequality, such as Florence Kelley, Alice Paul, Margaret

Dreier Robins, Carrie Chapman Catt, and Jane Addams, all play a role in this story, with Addams

in particular something of the patron saint of progressivism during the decade. As Robert

Johnston noted in his survey of recent Progressive literature, “the overwhelming sense from

recent scholarship is not only that women as a general collectivity were indeed empowered by

and through Progressivism, but that women were chiefly responsible for some of the most

important democratic reforms of the age.”31

The old, capital-P progressives that had congregated around Teddy Roosevelt – Harold

Ickes, Raymond Robins, Amos and Gifford Pinchot, William Allen White – have a part to play

as well, with Ickes’ falling away from Bull Moose Republican to FDR Democrat throughout the

29

Charles Forcey, The Crossroads of Liberalism; Croly, Weyl, Lippmann, and the Progressive Era, 1900-1925

(New York,: Oxford University Press, 1961), vii-ix.

30

Lynn Dumenil, The Modern Temper (New York: Hill and Wang, 1995), 23. The differences between The Nation

and The New Republic also highlight the generational differences within progressivism. In the words of historian

John Diggins: “The New Republic represented the twentieth century pragmatic strain of progressivism, The Nation

the nineteenth-century liberal strain. The difference between these two liberal currents was, among other things, the

difference between a relativistic approach to reform on one hand and a traditional faith in the standard democratic

road to social justice on the other, the difference between the empiricism of social engineering and the

humanitarianism of ‘good hope.’…Where The Nation had been, even during the war years, vigorously

antinationalist, the New Republic had looked to nationalism as the driving reform stimulus.” John Diggins.

“Flirtation with Fascism: American Pragmatic Liberals and Mussolini's Italy.” The American Historical Review,

Vol. 71, No. 2, (Jan., 1966), 499-500.

31

Johnston.

14

period a particularly useful window into the progressive politics of the decade. We will also see

urban reformers such as Al Smith and Fiorello LaGuardia of New York. Historians such as John

Buenker have argued that such urban reformers constituted a “vital part of the Progressive Era”

and have often been overlooked, to the detriment of our understanding of the period.32

Obviously, Smith and his ilk are particularly important in understanding the political events of

1924 and 1928.

Smith’s 1928 opponent, Herbert Hoover, has been deemed by historians such as Ellis

Hawley and Joan Hoff-Wilson as the “Forgotten Progressive.” As Hawley notes, Hoover was at

the center of “the most rapidly expanding sector of New Era governmental activity…[the]

transformation and expansion of the commerce secretariat.”33 African-American progressives

such as W.E.B. DuBois, James Weldon Johnson, and Walter White prove particularly valuable in

examining how the ideology and rhetoric of progressivism was transformed by the exigencies of

racial and cultural conflict. Socialists and former radicals – Eugene Debs, Victor Berger, Crystal

Eastman, Margaret Sanger, Roger Baldwin – are also present in this story, as they made common

cause with progressives in American life.34

32

Buenker, Urban Liberalism and Progressive Reform, 221.

Hawley, 117.

34

As Lynn Dumenil put it in The Modern Temper, citing the work of historian Nancy Weiss: The NAACP’s effort

in the 1920’s “exhibited the hallmarks of the progressive movement. It used careful investigations and publicity,

similar to the muckrakers’ approach, to expose an evil. And it tried legal tinkering – court cases and expanded

suffrage – to achieve democracy. As Du Bois put it in 1920, ‘The NAACP is a union of American citizens of all

colors and races who believe that Democracy in America is a failure if it proscribes Negroes, as such, politically,

economically, or socially.’ The black leaders in the NAACP, like progressives, clearly believed in the promise of

American life, in the system, and wanted to expand that promise to African Americans.” Dumenil, 291.

33

15

While these reformers do not all impact equally on every subject of discussion, taken

together I believe they form a wide-ranging palette with which to examine the questions that

drive this study.

Review of the Literature

The question of progressivism in the twenties – while once very much in favor – has not

been scrutinized in depth for awhile. Arthur Link’s 1959 essay “What Happened to the

Progressive Movement in the 1920’s?” remains the foundation for studies of this sort – In it,

Link hypothesized that the various members of the progressive coalition, although unable to

reunite or to capture a major party, were still very much alive and well in the New Era. In a 1966

article for the Journal of American History, which declared the Twenties a “New

Historiographical Frontier,” Burl Noggle ably surveyed the findings of then-recent monographs

on New Era progressivism:

An intriguing but most debatable theme that political historians lately have enlarged upon is that

of reform in the 1920s. Studies have begun to reveal survivals of Progressivism and preludes to

the New Deal in the decade. Clarke Chambers has found a strong social welfare movement at

work in the period, one concerned with child labor, slums, poor housing, and other problems that

Progressives before the 1920s and New Dealers afterward also sought to alleviate. Preston J.

Hubbard has studied the Muscle Shoals controversy of the 1920s and has demonstrated the

essential role that Progressives in the decade played in laying the basis for the New Deal’s TVA

system. Donald C. Swain has shown that much of the conservation program of the New Deal

originated in the 1920s. Howard Zinn has shown that Fiorello La Guardia, as congressman from

New York in the 1920s, provided a ‘vital link between the Progressive and New Deal eras. La

Guardia entered Congress as the Bull Moose uproar was quieting and left with the arrival of the

New Deal; in the intervening years no man in national office waged the Progressive battle so

long.’ La Guardia in the 1920s was ‘the herald of a new kind of progressivism, borne into

American politics by the urban-immigrant sections of the population.’ Not only his background

and his ideology, but also his specific legislative program, writes Zinn, were ‘an astonishingly

accurate preview of the New Deal.’” 35

35

Link. Plesur, The 1920's: Problems and Paradoxes; Selected Readings, 290.

16

All of these works mentioned by Noggle, along with his own work on Teapot Dome and

the immediate post-war years, have informed this study. So too has perhaps the best book-length

treatment of New Era progressivism since Noggle’s writing, Leroy Ashby’s 1972 tome The

Spearless Leader: Senator Borah and the Progressive Movement in the 1920s. In this work, as

noted previously, Ashby attributes the demise of progressivism in the Twenties not only to a

failure of leadership (i.e., Borah’s mercurial predisposition to always return to the Republican

fold at the last moment36), but to the aforementioned cultural clashes which irreparably

fragmented the progressive concept of the public interest.

Reflecting the general movement away from political history and towards cultural history

since Ashby’s day, most recent work on the Twenties – with some exceptions – has taken the end

of progressivism in 1919 as a given and tended to focus instead on the contentious cultural

clashes that marked the period, such as the rise of the second Ku Klux Klan, the Scopes trial, and

the emergence of the “New Woman.”37

However, there are some notable exceptions. David Goldberg’s 1999 synthesis

Discontented America devotes a chapter to the demise of progressivism in the Twenties.

Goldberg attributes the “Indian Summer of Progressivism” in the early 1920s to “widespread

36

Of this tendency, Senator George Norris once deadpanned that Borah had a dismaying habit of “shooting until he

sees the whites of their eyes.” Ashby, The Spearless Leader; Senator Borah and the Progressive Movement in the

1920's, 4.

37

Recent well-received books on the Klan of the 1920’s include Kathleen Blee’s Women of the Klan (1992), Citizen

Klansmen (1991), and Nancy McLean’s Behind the Mask of Chivalry (1994). Edward Larson’s Summer for the

Gods (1997) provides a nuanced and comprehensive overview of the Scopes trial, and Nancy Cott’s The Grounding

of Modern Feminism (1987) ably surveys the new challenges facing feminism in the post-suffrage period. Other

important works on the New Era include Ann Douglas’ A Terrible Honesty, George Chauncey’s Gay New York, and

Lynn Dumenil’s The Modern Temper, all of which emphasize the cultural transformations of the period.

17

agricultural discontent,” yet ultimately concludes that “progressivism as a movement never

recovered from the 1924 defeat” of Robert La Follette and the Progressive Party.38

And in his 2003 book Changing the World: American Progressives in War and

Revolution, the late Alan Dawley argues in his final chapter that, “as progressivism died out in

the higher circles of power, it was reborn in social movements down below. It came to life in the

vital postwar peace movement, in the hard-fought struggles of organized labor, in the protests of

small farmers, and in the spirited defense of civil liberties.” Instead, Dawley argues, “keepers of

the faith took a turn toward economics, threw in their lot with the producing classes, and set out

to win economic justice for farmers and workers. In taking the economic turn, postwar reformers

edged closer to the left and set progressivism on a path it would follow for the next three

decades.”39

Chapter Outline

With the exception of a brief prologue and epilogue, this study is broken down into three

main parts: Part One, “Crack-Up: From Versailles to Normalcy,” covers the plight of

progressives from the signing of the Armistice to the election of Warren Harding in 1920. While

this first section is told mostly in narrative form, Parts Two and Three, “Confronting Normalcy”

and “A New Era” – which culminate in the elections of 1924 and 1928 respectively – cover the

experiences of progressives across the decade by subject.

38

David Joseph Goldberg, Discontented America : The United States in the 1920s (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins

University Press, 1999), 65.

39

Alan Dawley, Changing the World: American Progressives in War and Revolution (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 2003), 297, 313.

18

“I am honestly sorry,” Jane Addams would write in the introduction of her 1930 book

The Second Twenty Years at Hull House, “to write so much in this book of the effects of the

world war.” This was a common refrain throughout the period of study – F. Scott Fitzgerald

attributed the entire character of the decade to “all the nervous energy stored up and unexpended

in the war.” “I have no doubt,” said Clarence Darrow, “but what the war is largely responsible

for the reactionary tendency of the day.” The war and its aftermath “all but destroyed my picture

of America,” said Frederic Howe. “It does not come to life again.” To John Haynes Holmes, it

proved the “America we loved was gone, and in its place was just one more cruel imperialism.

The discovery ended a movement which had for its purpose the protection and vindication of an

ideal America.”40

In sum, the period from 1918 to 1920 would set the stage for most of the decade to come.

Chapter One and Two of this section cover progressive reaction to the demoralizing failures of

Woodrow Wilson at Versailles and the battle over the League of Nations respectively. Chapter

Three surveys the long, dark night of the soul that was 1919, when a steady diet of strikes, race

riots, and repression conspired to bury the progressive post-war dream. Chapter Four takes up the

tale with the election of 1920, when, as a result of all the calamities covered in the first three

chapters, amiable mediocrity Warren Harding won the most decisive presidential victory in a

century.

With the stage thus set, Part Two – “Confronting Normalcy” – covers much of the

experience of 1920-1924, a time that – contrary to the Gatsbyesque view of the Twenties in the

40

Jane Addams. The Second Twenty Years at Hull House. The MacMillan Company (New York: 1930), 7-9.

Dawley, 214-215. “Where are the Pre-War Radicals,” The Survey, February 1, 1926.

19

popular imagination – was in many ways as hard-fought and full of conflict as the immediate

post-war period. The time usually thought of as the Roaring Twenties – a boom era when

progress stagnated and business values reigned triumphant – did not really come to pass until

Calvin Coolidge ascended to the presidency. In the years of Harding Normalcy, the country

remained in the grip of a post-war recession, and, even as progressives passed the SheppardTowner Act, rolled back the legal excesses of the Red Scare, moved the country toward a

disarmament footing, and exposed systemic corruption in the administration, the nation as a

whole saw labor violence erupt in West Virginia and Herrin, Illinois, race wars flare up in Tulsa

and Rosewood, and a strike wave redound across the nation in 1922.

Chapter Five, “The Politics of Normalcy,” begins the examination of this period by

chronicling the tenor, conduct, and achievements of the Harding administration, attempts by

congressional progressives to organize in opposition over the course of the decade, and efforts to

establish and maintain the virtue of good government in American life, by decrying lobbies,

promoting campaign finance reform, and railing against the corruption within Warren Harding’s

White House.41

Chapter Six, “Legacies of the Scare,” focuses on the newfound attention paid by many

progressives in the Twenties to issues of civil liberties, including the right to organize, during the

Twenties, and covers such as issues as the struggles of the ACLU, the Sacco-Vanzetti trial, the

41

It was “persistent investigative work by Montana senators Burton K. Wheeler and Thomas Walsh,” writes David

Goldberg in his recent survey of the Twenties, which “began to uncover the full scope of the Teapot Dome scandal,

and progressives remained convinced that the ‘radical swing’ would be carried into the election year.” Similarly,

Burl Noggle’s 1962 work on Teapot Dome argued that it was progressive conservationists, namely friends of

Gifford Pinchot, who set the Teapot Dome scandal in motion. Goldberg, Discontented America, 60. Burl Noggle,

Teapot Dome: Oil and Politics in the 1920's (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1962), vii-ix.

20

NAACP’s fight for anti-lynching legislation, and the labor conflicts of the period.42 Chapter

Seven, “America and the World,” examines the nationalistic and anti-imperialistic foreign policy

of “peace progressives,” honed during the battle over the League of Nations, and covers such

issues as the continued question of American involvement in the League and World Court, the

disarmament and outlawry movements, and immigration restriction. Closing out Part Two,

Chapter Eight covers the story of the election of 1924, when disaffected groups propelled Robert

La Follette and the Progressive Party to one of the more impressive third-party candidacies of the

century.

Part Three, “A New Era,” takes up the story after Coolidge’s impressive victory in 1924.

It begins with Chapter Nine, “The Business of America,” highlighting the ascendancy of the

business culture in government and American life, and covering Harding’s budget reforms, the

Coolidge administration, the work of Herbert Hoover and Andrew Mellon, the rise of welfare

capitalism, and the enthronement – particularly among a younger generation – of professionalism

and expertise as progressive virtues. Chapter Ten, “Culture and Consumption,” examines the

rocky shoals progressives faced in trying to navigate between consumerism and cultural conflict

during the New Era. On one side, even as emerging technologies like radio and the cinema

suggested intriguing new possibilities for enlightening public opinion, conspicuous consumption

and advertising threatened to overwhelm the basic philosophical underpinnings of progressive

42

Leroy Ashby argues that Senator William Borah, at least, “emerged as a leading spokesman for civil liberties.”

“Borah was convinced,” Ashby writes, “that a prerequisite for reform was free discussion and, to that end,

progressives must ‘fight for the right to say anything at all.’ Ashby also quotes The New Republic “angrily”

observing of the Red Scare that “a ‘phantom army of shibboleths’ continued to rush forward ‘to attack any and every

program, squeaking and parroting sounds about “socialism” and “bolshevism” and “business enterprise.”’”

Whatsmore, sociologist Paul Starr recently concluded in his history of the media that “the disillusionment with the

war and repression of dissent started Progressives thinking more seriously about the value of protections against the

abuse of state power.” Ashby, The Spearless Leader; Senator Borah and the Progressive Movement in the 1920's,

27-28. Paul Starr, The Creation of the Media : Political Origins of Modern Communications (New York: Basic

Books, 2004), 285.

21

ideology. On the other hand, traditionalist reactions to the pace of change, like the Ku Klux Klan,

anti-Scopes fundamentalism, and the apparent failure of prohibition seemed a mocking shadow

of earlier progressive aspirations.43

Chapters Eleven, “New Deal Coming,” surveys the policy foundations of the New Deal

laid down in the immediate postwar era and Twenties, including former suffragists’ defense of a

more robust federal welfare state, the innovations of the Al Smith administration in Albany,

attempts to rein in the power of the Supreme Court, and George Norris’ lonely fight for public

power. Finally, Chapter Twelve concludes the tale with an examination of the election of 1928

and its aftermath, including the personal attempts by progressives, over the course of the decade,

to stave off defeatism and despair.

Writing in The Survey on New Year’s Day 1921 in answer to the question “What Else

Must Be Done To Make This a More Livable World,” Felix Adler, founder of the Society for

Ethical Culture, argued that “the best satisfaction we can hope for is the consciousness of

creative activity in the effort to make it better.” In a decade that often saw reaction in the driver’s

seat and the ideals that had sustained the progressive experiment for decades under assault, that

consciousness of a fight hard-waged – and the companionship of those also engaged in the

struggle – would often be the only consolation for progressives. In the ten years between the

Armistice and the election of 1928, their fight for change would be uphill all the way.44

43

Speaking of the progressive notion of a “public good,” Leroy Ashby writes, “[t]hat idea, and the moralistic

rhetoric that had surrounded it, had struck common chords in the generally confident years of the early 1900’s. But

in the Twenties, deeply rooted cultural antagonisms had surfaced, dividing wets and drys, town and country, oldstock and new-stock Americans,” and thus the concept of the “public good” could not withstand these impassioned

cultural schisms. Ashby, 12.

44

“What Else Must Be Done to Make This a Livable World?” The Survey, January 1st, 1921, 498

22

PROLOGUE: INAUGURATION DAY, 1921

“When one surveys the world about him after the great storm, noting the marks of

destruction and yet rejoicing in the ruggedness of the things which withstood it, if he is an

American he breathes the clarified atmosphere with a strange mingling of regret and new

hope.”45 So began Warren G. Harding on the crisp, cold morning of March 4, 1921, soon after

taking the oath of office to become the 29th president of the United States. A return to

“normalcy” had been Harding’s solemn vow as a presidential candidate, of course, and

everything from the stripped-down spectacle of the day’s events – at the president-elect’s

request, the customary ball had been abandoned and the usual parade had been scaled back – to

the content of the inaugural address worked to convey the impression that this “great storm” had

passed, that the long national nightmare of the Wilson years was ended, and that the new steward

in the White House would steer a return course to pre-war stability.46

“Our supreme task is the resumption of our onward, normal way,” argued the new

president. “Reconstruction, readjustment, restoration, all these must follow.” In their

overreaching, Harding suggested, the policies of Woodrow Wilson had disrupted the natural

order of things. “[N]o statute enacted by man can repeal the inexorable laws of nature. Our most

dangerous tendency is to expect too much of government,” he warned. Surveying the American

economy after eight years of Democratic rule, Harding thought “[t]he normal balances have been

45

Warren Harding, “Inaugural Address,” March 4, 1921. Reprinted at Bartleby.com

(http://www.bartleby.com/124/pres46.html).

46

New York Times, Jan 11, 1921, p. 1. A frequent critic of excess government expenditures, progressive Senator

George Norris of Nebraska had urged Harding, if he desired to be extravagant on his inauguration day, to follow the

example of Abraham Lincoln, who allegedly “kissed thirty-four girls on that occasion…Nobody will deny the same

privilege to President-elect Harding, if he can find girls who are willing – and I presume he can – so long as it is not

charged up to the taxpayers of the country and they do not have to pay for it.” Richard Lowitt, George W. Norris:

The Persistence of a Progressive, 1913-1933 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1971), 134-135.

23

impaired, the channels of distribution have been clogged, the relations of labor and management

have been strained.” And, as the world had “witnessed again and again the futility and the

mischief of ill-considered remedies for social and economic disorders,” the new President

promised a simpler and humbler approach to governance on his watch. “I speak for

administrative efficiency, for lightened tax burdens, for sound commercial practices, for

adequate credit facilities, for sympathetic concern for all agricultural problems, for the omission

of unnecessary interference of Government with business, for an end to Government's

experiment in business, and for more efficient business in Government administration.”47

In short, as per his decisive electoral mandate – Harding had defeated Democratic

nominee and Ohio Governor James A. Cox the previous November with 60.3% of the popular

vote (as opposed to only 34.1% for Cox, the largest popular vote differential in modern

American history) – Harding promised an end to Wilsonian hubris, a light government touch and

the type of sturdy, well-practiced, and business-minded leadership that had marked Republican

administrations since the days of Williams McKinley and Taft. As the New York Tribune

summed up Harding’s remarks, “he looks at our political and economic life with no innovating

eye. He is a conserver, and would stick to the time tested. The old America is good enough for

him.”48

And yet, however much Harding’s words conveyed a safe and salutary return to the way

things ought to be, signs of change were in the air, as perhaps exemplified by the “startlingly

modern jazz number” played as America’s new First Lady, Florence Harding, whom her

47

48

Harding, “Inaugural Address.”

Washington Post, Mar. 6, 1921, p. 30.

24

husband and his confidants referred to as “the Duchess,” took her seat.49 For Harding’s inaugural

that morning was not only the first to employ an automobile rather than the conventional

carriage, it was also the first to be amplified by loudspeakers and the first broadcast across the