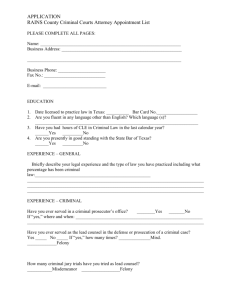

Defense Attorney Resistance

advertisement