Bay Area—Plug-In Electric Vehicle Readiness Plan

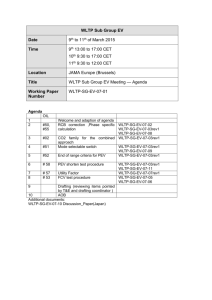

advertisement