consumption - labor income

advertisement

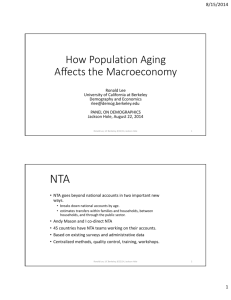

A global overview of population aging and intergenerational transfers, and some implications for economic growth Ronald Lee (UC Berkeley) Santiago, October 20, 2009 NIA R37-AG025488 and MEXT.ACADEMIC FRONTIER to NUPRI in Japan Deep thanks to NTA country teams, Gretchen Donehower, and Andy Mason. Plan of talk • Consider some economic consequences of the demographic transition, including population aging. • Draw on results of the National Transfer Accounts project (NTA) for 23 countries. • Focus on Latin America. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Latin American NTA Country Teams — many members are at this meeting. • Brazil – – – – • Lanza, Queiroz, Bernardo Marri, Izabel Renteria, Elisanda Perez Turra, Cassio Chile – Bravo, Jorge – Holz, Mauricio • Costa Rica – Collado, Andrea – Rosero-Bixby, Luis – Zuniga, Paola • Mexico – Ivan Mejia – Félix Vélez Fernández-Varela – Juan Enrique • Uruguay – Bucheli, Marisa – Gonzalez, Cecilia Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 1. Changing population age structure across the demographic transition: the case of Mexico, 1900-2100 • Demographic transition is process of moving from initial high fertility and high mortality to low fertility and low mortality, and the accompanying changes in population size and age composition. • Most transitions follow a classic pattern, but Latin America has many exceptions. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 • In most Third World countries fertility decline started around 1965 or later. • Fertility decline started much earlier in some Latin American countries – E.g. in 1900 or earlier in Argentina, Uruguay, Cuba, Chile. – These declines stalled at mid century, contrary to classic pattern. • Mortality decline more typical, starting sometimes before 1900, some times later. • Diversity, no single pattern in Latin America. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Mexico, 1900-2100 • In some respects classic – Mortality decline preceded fertility decline by many decades – Fertility declined steadily to near replacement (TFR=2.3) and life expectancy is high (75 years) • In other respects, not typical – Mexican Revolution perturbed fertility and mortality in early 20th century. – High net outmigration (not so unusual). • Transition data based on Perez-Brignoli (2009) reconstruction and on UN data. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 The demographic transition in Mexico Total Fertility Rate Life Expectancy 7 90 5 4 3 2 80 Average Annual Growth Rate Life Expectancy from Birth 6 Total Fertility Rate Growth Rate 4 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 1 1900 1950 2000 2050 0 1900 2100 Population Size 2050 2100 2 1 0 -1 1900 1950 2000 2050 2100 Simulated 1 120 Total Population (millions) Total Population (millions) 2000 Dependency Ratios 140 100 80 60 40 20 0 1900 1950 3 1950 2000 2050 2100 Perez-Brignoli Total 0.8 UN Historical 0.6 Old (65+) UN Projected Young (<15) Note that simulation includes assumption of net outmigration by ages 15-64 of approximately 0.6% per year from 1980. (Data driven to match observed population sizes.) 0.4 0.2 Oldest Old (85+) 0 1900 1950 2000 2050 2100 Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Dependency Ratios Total Population (millions) 1 Total 0.8 0.6 Old (65+) 0.4 Young (<15) 0.2 Oldest Old (85+) 0 1900 1950 2000 2050 Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 2100 2. Economic behavior varies across the life cycle – dependency and surplus production • The economic life cycle starts with child dependency and ends with old age dependency. – Children consume much more than they produce, particularly if enrolled in school. – Elderly consume much more than their labor earnings. • NTA estimates patterns of labor income and consumption over the life cycle. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Cross-sectional NTA estimates of labor income by age. • Averaged across all people of given age – male and female – Employed, self-employed, fringe benefits – Formal or informal sectors. – in labor force or not. • Divided by average labor income for age 30-49 in each country to standardize. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 NTA Age Profiles of Labor Income for Four Rich and Four Poor Countries (unweighted averages) 1.2 Children have more labor income in poor countries. Labor Income/Av labor inc 30-49 1 Rich (JP,US,SE,FI) Poor (ID,IN,PH,KY) 0.8 Income drops suddenly around age 60 in rich countries: Pension structure. Income peaks earlier in poor countries. . 0.6 0.4 In old age, people in poor countries work more. 0.2 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Age Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 70 80 90 100 NTA Age Profiles of Labor Income, for Four Rich, Four Poor, and Five Latin Ameictran Countries (unweighted averages) 1.2 Latin America (BR,CL,CR,MX,UY) Latin America looks similar to poor countries. Why? Labor Income/Av labor inc 30-49 1 Rich (JP,US,SE,FI) Poor (ID,IN,PH,KY) 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Age Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 70 80 90 100 Age Profiles of Labor Income Five Latin American Countries 1.2 BR CL CR MX UY 1 Ratio to av yl(30-49) Early decline in Brazil after 50. 0.8 Related to pension structure? 0.6 0.4 Lower in Uruguay above 65.. 0.2 Related to pension structure? 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 Age Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 60 70 80 90 Consumption (cross-sectional NTA estimates) • Average for all people of given age • Includes – Private expenditures by households, allocated by age within the household (private health and education estimated separately). – Public in-kind transfers (e.g. education, health care, long-term care). • Standardized by dividing by average labor income of each country. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 NTA Age Profiles of Labor Income and Consumption for Four Rich and Four Poor Countries 1.4 Rich (US,JP,SE,FI) 1.2 Consumption rises with age in rich countries, partly health spending, mainly public. Ratio to av yl(30-49) Poor (ID,IN,PH,KE) 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 Flat consumption profile in poor from 20 to end of life. More human capital investment in rich countries. 0.2 Co-resident elders, household sharing? 0 1 11 21 31 41 51 Age Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 61 71 81 91 Age Profiles of Labor Income and Consumption for Four Rich, Four Poor, and Five Latin American Countries 1.4 Latin America (BR,CH,CR,MX,UY) Rich (US,JP,SE,FI) Ratio to av yl(30-49) 1.2 Level is very high relative to labor income. Why? Poor (ID,IN,PH,KE) 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 Shape of LA is more similar to poor countries. 0.2 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 Age Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 60 70 80 90 Why is the Latin American consumption so high relative to average labor income? • Ratio of aggregate consumption to aggregate labor income in National Income and Product Accounts is very high in Latin America (5 out of top 7 among NTA countries). – Nonlabor income like remittances and natural resources. • Probably reflects very low national saving rates in the region. • Why is saving low? See Mario Gutiérrez (2007) CEPAL study on this question. • Could it be linked to generous public pensions? Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Age Profiles of Consumption for Five Latin American Countries 1.2 Ratio to av yl(30-49) 1 0.8 0.6 Consumption rises strongly at old ages in Brazil. BR CL CR MX UY 0.4 0.2 Generous public pensions? Consumption falls in old age in Mexico. Low public pensions? 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 Age Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 60 70 80 90 Age Profiles of Labor Income and Consumption for Four Rich, Four Poor, and Five Latin American Countries 1.4 Latin America (BR,CH,CR,MX,UY) Rich (US,JP,SE,FI) 1.2 Ratio to av yl(30-49) Consumption minus labor income is “life cycle deficit”. Poor (ID,IN,PH,KE) 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 Age Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 60 70 80 90 The Life Cycle Deficit (consumption - labor income) in rich, poor, and Latin American countries 1.4 In Latin America, there is not much surplus labor income (small age range and low value), whereas life cycle deficits are large. (Consumption - Labor Income)/Av yl(3049) 1.2 1 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 -0.2 -0.4 Latin Am -0.6 -0.8 Age Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Rich Poor 3. Age structure and economic behavior: support ratios • “Effective labor” is sum over age of population times labor income. • “Effective consumers” is similar. • “Support Ratio” is ratio of effective labor to effective consumers. • Other things equal, consumption per effective consumer is proportional to the support ratio. – Similarly for per capita income. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Support Ratios for Mexican Population (simulations and UN projections, with average of 5 Latin American country profiles) 0.80 Aggregate YL / Aggregate C 0.75 0.70 0.65 0.60 0.55 0.50 1950 1970 1990 2010 2030 Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Year 2050 2070 2090 Support Ratios for Mexican Population (simulations and UN projections, with average of 5 Latin American country profiles) First dividend period adds .7% per year to consumption growth from 1975 to 2025. 0.80 Aggregate YL / Aggregate C 0.75 0.70 0.65 0.60 0.55 0.50 1950 1970 1990 2010 2030 Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Year 2050 2070 2090 Support Ratios for Mexican Population (simulations and UN projections, with average of 5 Latin American country profiles) 0.80 Aggregate YL / Aggregate C 0.75 0.70 0.65 Population aging. Subtracts .4% per year from consumption growth from 2025 to 2060 0.60 0.55 0.50 1950 1970 1990 2010 2030 Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Year 2050 2070 2090 Support Ratios for Mexican Population (simulations and UN projections, with average of 5 Latin American country profiles) 0.80 Aggregate YL / Aggregate C 0.75 0.70 0.65 Contrast between dividend phase and aging is 1.1%/yr 0.60 0.55 0.50 1950 1970 1990 2010 2030 Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Year 2050 2070 2090 0.80 Support Ratios for Latin America (Own-country populations, average of 5 country profiles) BR CL 0.75 CR Support Ratio MX 0.70 UY 0.65 MX is same as last slide 0.60 Uruguay is different because of its very early fertility decline. 0.55 0.50 1950 1970 1990 2010 2030 2050 Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Year 2070 2090 0.80 Support Ratios for Latin America (Own-country populations, average of 5 country profiles) Approximate demographic dividend phase BR CL 0.75 CR Support Ratio MX 0.70 UY 0.65 0.60 Approximate population aging phase 0.55 0.50 1950 1970 1990 2010 2030 2050 Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Year 2070 2090 0.80 Support Ratios for Latin America (Own-country populations, average of 5 country profiles) BR CL 0.75 CR Support Ratio MX 0.70 UY 0.65 Except for Uruguay, the dividend contributes .50 to .75 %/yr to consumption growth 1970-2020. 0.60 0.55 Population aging subtracts .35 to .40%/yr 2020 to 2070.. 0.50 1950 Contrast is around 1%/yr. 1970 1990 2010 2030 2050 Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Year 2070 2090 4. In older populations, more consumption by elderly people is funded somehow. • Illustrate with Indonesia (young) and Japan (old). Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 P e r c a p ita c o n s u m p tio n o r la b o r in c o m e Per capita consumption and labor income by age for Indonesia and Japan 1,000,000 Indonesia, 2002 800,000 600,000 400,000 200,000 0 20 40 60 80 100 Per capita consumption or labor income in Yen Age 500,000 Japan, 2004 400,000 300,000 200,000 100,000 0 20 40 60 80 Age Indonesia NTA Maliki; Japan NTA Ogawa 100 The aggregate lifecycle deficit at each age (population by age times per capita age profiles) Aggregate Life Cycle Deficit for Indonesia (2005) in Rupiah 30,000 20,000 10,000 - 0 20 40 60 80 100 (10,000) (20,000) (30,000) Age Aggregate Life Cycle Deficit for Japan (2004) in Yen Express the total old age aggregate life cycle deficit as a share of aggregate consumption at all ages. Measures the importance of consumption by the elderly in excess of their labor income. 5,000 Aggregated Consumption - Labor Income Aggregated Consumption - Labor Income 40,000 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,000 (1,000) 0 20 40 60 80 100 (2,000) (3,000) (4,000) (5,000) Age Indonesia NTA Maliki; Japan NTA Ogawa The older the population, the greater this share. Calculate aggregate deficit as share of total consumption. Aggregate old age deficit is funded by assets and transfers (public and private) Aggregate Life Cycle Deficit for Indonesia (2005) in Rupiah Aggregated Consumption Labor Income 40,000 30,000 20,000 10,000 - 0 20 40 60 80 100 (10,000) (20,000) (30,000) Age Aggregate Life Cycle Deficit for Japan (2004) in Yen Aggregated Consumption - Labor Income 5,000 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,000 (1,000) 0 20 40 60 80 100 • Green arrows show transfers from surplus of prime working years. • Red arrows show asset income consumed by elderly out of earlier savings. (2,000) (3,000) (4,000) (5,000) Age Indonesia NTA Maliki; Japan NTA Ogawa LCD 65+ as a Share of Total Consumption 0.25 Aggregate Old Age Consumption Deficit as a Share of Total Consumption vs Proportion of Population 65+ JP SE Kenya: 2% Japan: 22% 0.2 0.15 ES SL AT HU FI FR US UY Most difference due to population aging. Population aging means more assets. 0.1 CL TW TH BR SK CR CN IDMXIN 0.05 Old age deficit is funded partly by asset accumulation. KY PH y = 1.1921x - 0.0189 2 R = 0.9732 0 0 0.05 0.1 0.15 Share of Population 65+ Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 0.2 0.25 Implications for capital accumulation • Population aging raises need to provide for old age deficit. • If met by more asset accumulation, then population aging raises asset income and perhaps labor productivity. • If met by public or private transfers, then population aging just raises the transfer burden on workers. • Policy should find right balance of assets and transfers. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 5. How is the elderly life cycle deficit funded in different countries? Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Funding the Old-age Deficit in the US Components of Lifecycle Deficit, US 2003 70000 Asset income and dissaving 60000 Public Asset-Based Reallocations Private Asset-Based Reallocations Public Transfers Private Transfers 50000 40000 Net public transfers (public pensions, health care, etc., less taxes paid). US $ 30000 20000 10000 0 -10000 Net private transfers – interand intra-household transfers. -20000 -30000 0 3 6 9 12 15 18 21 24 27 30 33 36 39 42 45 48 51 54 57 60 63 66 69 72 75 78 81 84 87 90 Age Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Shares of assets, public transfers, and private transfers, differs from country to country. • The % shares of each add to 100%. • We can show these on a “triangle graph”. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Triangle graph shows funding shares of life cycle deficit of elderly (65+, consumption – labor income): Assets, Public Transfers, Private transfers At each corner, 100% of deficit is funded by that item. PH nearly 100% Assets. AT nearly 100% Public Transfers On each side, one item is 0. TH has 0 public trabnsfers. JP has 0 private transfers. Taiwan is near the middle, with bbbequal shares (1/3) from each. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Triangle graph for funding life cycle deficit of 65+: East Asian countries show familial support of elderly (except Japan) Japan relies 2/3 on public transfers, rest on assets. Family transfers are 0! Other E. Asian rely less than 1/3 on public transfers. China relies 60% on family. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Triangle graph for funding life cycle deficit of 65+: Latin American elderly make private transfers to others. Brazil.s public transfers to elderly are greater than any other country’s. Brazil, Mexico, and Uruguay make larger downward transfers than any other. Mexico relies mostly on assets. Why? Mexican households own no more assets than in other LA countries. They use assets for consumption because unlike the other NTA countries, public pensions are small. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Triangle graph for funding life cycle deficit of 65+: in US and Europe elderly also transfer to others. US relies less on public transfers, more on assets. In Japan, younger elderly make family transfers, older elderly receive them. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 6. The demographic transition also promotes investment in human capital. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Human Capital • Parents choose between number of children and amount to invest per child (Quantity-quality tradeoff) • As economies develop parents opt for fewer children and spend more per child (Becker; Becker and Lewis, Willis). • Aging (low fertility) will be accompanied by more human capital, regardless of causal direction. • The human capital “response” helps to offset the negative effect of population aging on the support ratio. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Empirical Relationship between Human Capital and Fertility • NTA measure of Human Capital (HK) investment – NTA measures public and private spending per capita at each age for health and for education – Sum these for ages 0-17 for health and 0-26 for education – Normalize on average labor income ages 30-49 • Compare HK to Fertility in preceding five years Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 Cross-sectional Relationship 7 6 SE JP SI TW Estimated elasticity d ln HK / d ln TFR is -0.913 Human capital 5 MX FR ESKR US AT HU FI BR TH CR DE CL UY 4 3 CN 2 PH ID IN 1 KE 0 0 1 2 3 Total Fertility Rate Source: Lee and Mason, forthcoming, European Journal of Population (2009). Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 4 5 6 Time Series Relationship 7 Number of Observations Japan 5 Taiwan 27 United States 23 6 Human capital spending Estimated elasticities Japan -1.46 Taiwan -1.40 United States -0.72 Taiwan 1977-2003 5 Japan 1984-2004 4 3 US 1960-2003 2 1 0 0 1 2 Total Fertility Rate Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 3 4 Population aging is accompanied by increased investments in HK of children • Raises the productivity and earnings of labor force in future • Substitutes HK for number of workers • Offsets falling support ratios. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 7. Policy can alleviate the economic impact of population aging • Population aging will certainly cause problems. – Fiscal sustainability of public programs is a huge problem for many Latin American countries. I did not discuss this. – Population aging will cause falling support ratios, which will reduce consumption, other things equal, by 1%/yr relative to dividend phase. – Some risk that that fiscal pressures of aging will crowd out human capital investments in children. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009 But… • Population aging raises the demand for capital by raising the share of old age consumption in the economy. – If old age consumption is funded at least in part by assets rather than transfers, then population aging will lead to higher capital/labor ratio. – Policy should find the right balance between unfunded public pensions and funded programs, either public or private. – Avoid mistakes of current industrial nations in this regard. • The low fertility that causes population aging also goes with increased HK investment in children, and higher labor productivity in the future. Policy should support investments in human capital of children. Ronald Lee, UC Berkeley, 2009