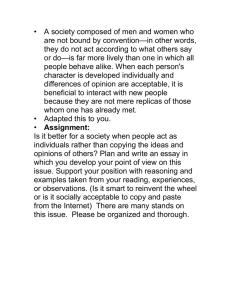

Copyrights and Creative Copying

advertisement