Did Learned Hand Get It Wrong?: The Questionable Patent

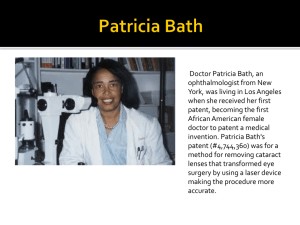

advertisement