Saving the Dust Bowl - Washington State History Museum

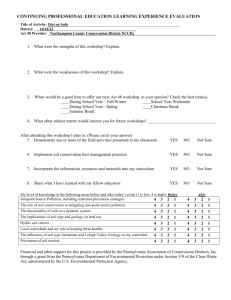

advertisement