November 5, 2014

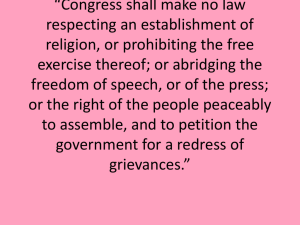

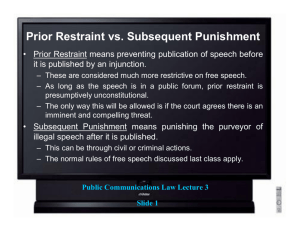

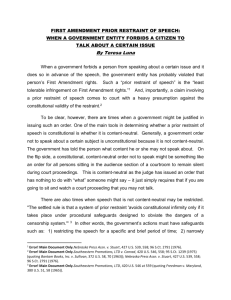

advertisement

EDITORIAL ON THE NOVEMBER 5, 2014, PUBLIC MEETING WHAT HAPPENED TO MY REPORT? The answer to the question “What happened to my report” is complete (pre-publication) censorship. Censorship issued by Chief Clerk Wilson backed by Commissioners McCarrier and Pinkerton. Censorship of free speech is nothing more than prior restraint. If you don’t like what might be said—stop it before it happens. If you didn’t like what was said—prevent it from being posted on a public Commissioner’s webpage. And most definitely the IT Director was immediately advised to remove the Utube link so the public was not able to view a Public Commissioners’ Meeting— specifically, the November 5, 2014, Public Meeting (See attached supporting documentation.). As a consequence, when the link was removed from my webpage, all historical Public Meetings were removed and are not able to be accessed from the public County website that your tax dollars are supporting. William Blackstone, English and legal Jurist, noted in his Commentaries that “Freedom of the Press” is defined as the right to be free from prior restraints. He further held that a person should not be punished for speaking or writing the truth with good motives and for justifiable ends. “Every freeman has an undoubted right to lay what sentiments he pleases before the public; to forbid this, is to destroy the freedom of the press; but if he publishes what is improper, mischievous or illegal, he must take the consequence of his own temerity.”(4 Bl.Com.151, 152) Most notably, this view was the common legal understanding when the United States Constitution was adopted. Thereafter, First Amendment protections of freedom of speech and the press were extended to protect honest error or truth even if published for questionable reasons. The definition of prior restraint is: an attempt to prevent publication or broadcast of any statement, which is an unconstitutional restraint on free speech and free press (even in the guise of anti-nuisance ordinance). In Near v. Minnesota, 283 U.S. 697(1931), the U.S. Supreme Court held prior restraints to be unconstitutional, except in limited national security issues. The Court’s ruling was a result of Minnesota’s Gag Law and the government’s silence of Jay Near’s The Saturday Press, a local newspaper, that published articles pertaining to Minneapolis’s elected officials alleged illicit activities, including gambling, racketeering and graft. The Near Court held that the state had no power to enjoin the publication of the paper in this way—that any such action would be unconstitutional under the First Amendment. Citing Patterson v. Colorado, 205 U.S. 454, the Court stated that “the statute in question cannot be justified by reason of the fact that the publisher is permitted to show, before injunction issues, that the matter published is true and is published with good motives and for justifiable ends. . . . it would be but a step to a complete system of censorship. . . .The preliminary freedom, by virtue of the very reason for its existence, does not depend, as this court has said, on proof of truth.” The Near Court further cited the Patterson Court by stating: “in the first place, the main purpose of such constitutional provisions is ‘to prevent all such previous restraints upon publications as had been practiced by other governments,’ and they do not prevent the subsequent punishment of such as may be deemed contrary to the public welfare.” Historically, the Supreme Court considered prior restraint censorship as oppressive. Such dictatorial censorship infringed on one’s First Amendment Constitutional Rights because the restricted subject matter was unilaterally prevented from being heard or distributed. Prior restraint removes an idea, suggestion, concept, opinion, report, material, comment, truth or subject matter completely out of the public forum and free market. This view was supported by the U.S. Supreme Court in Nebraska Press Association v. Stuart, 427 U.S. 539 (1976), a case covering a criminal pretrial story, by stating “prior restraints on speech and publication are the most serious and the least tolerable infringement on First Amendment rights. . . . A prior restraint, by contrast and by definition, has an immediate and irreversible sanction. If it can be said that a threat of criminal or civil sanctions after publication ‘chills’ speech, prior restraint ‘freezes’ it at least for a time.” Press coverage, reporting and commentary on the criminal justice system is at the core of First Amendment values, for the operation and integrity of that system is of crucial import to citizens concerned with the administration of government. Secrecy of judicial action can only breed ignorance and distrust of courts and suspicion concerning the competence and impartiality of judges; free and robust reporting, criticism, and debate can contribute to public understanding of the rule of law and to comprehension of the functioning of the entire criminal justice system, as well as improve the quality of that system by subjecting it to the cleansing effects of exposure and public accountability. See In re Oliver, 333 U.S. 257 (1948). My November 5, 2014, report given at a Public Meeting not only violated my Constitutional First Amendment Right to Free Speech, it violated the Sunshine Law by not allowing a matter voiced as public concern from being disseminated by an Elected County Commissioner to constituents. All subject matter regarding the criminal justice process which also involved the Children and Youth Agency was oppressively censored from you. The damage can be particularly great when the prior restraint falls upon the communication of news and commentary on current events. Truthful reports of public judicial proceedings have been afforded special protection against subsequent punishment. See Cox Broadcasting Corp v. Cohn, 420 U.S. 469 (1975); see also, Craig v. Harney, 331 U.S. 367 (1947). For the same reasons the protection against prior restraint should have particular force as applied to reporting of criminal proceedings, whether the crime in question is a single isolated act or a pattern of criminal conduct. Furthermore, a concurring opinion stated "by placing the information in the public domain on official court records, the State must be presumed to have concluded that the public interest was thereby being served. Public records by their very nature are of interest to those concerned with the administration of government, and a public benefit is performed by the reporting of the true contents of the records by the media. The freedom of the press to publish that information appears to us to be of critical importance to our type of government in which the citizenry is the final judge of the proper conduct of public business. In preserving that form of government the First and Fourteenth Amendments command nothing less than that the States may not impose sanctions on the publication of truthful information contained in official court records open to public inspection." Pursuant to prior-restraint analysis, courts have rejected government attempts to criminalize the dissemination of certain information. In Landmark Communications v. Virginia,435 U.S. 829 (1978), the U.S. Supreme Court held that a Virginia newspaper accurately reporting on a pending investigation of a state judge could not be prosecuted under a state law prohibiting anyone from divulging information about such investigations. According to the Court, the state’s interest in protecting the reputation of judges was insufficient to justify the punishment of accurately reported information. A logical extension of Landmark would mean that any reporting and commentary after a criminal investigation and trial is completed is protected under the First Amendment. Contact me directly for additional information and to express your views. I will not use prior restraint. Jim Eckstein Commissioner